第八章 市场革命

原标题:The Market Revolution

Source / 原文:https://www.americanyawp.com/text/08-the-market-revolution/

I. Introduction

一、引言

In the early years of the nineteenth century, Americans’ endless commercial ambition—what one Baltimore paper in 1815 called an “almost universal ambition to get forward”—remade the nation. Between the Revolution and the Civil War, an old subsistence world died and a new more-commercial nation was born. Americans integrated the technologies of the Industrial Revolution into a new commercial economy. Steam power, the technology that moved steamboats and railroads, fueled the rise of American industry by powering mills and sparking new national transportation networks. A “market revolution” remade the nation.

19世纪初期,美国人无休止的商业野心——一家巴尔的摩报纸在1815年称之为“几乎普遍的向前进的雄心”——重塑了这个国家。在独立战争和内战之间,一个旧的自给自足的世界消亡了,一个新的更具商业性的国家诞生了。美国人将工业革命的技术融入了新的商业经济中。蒸汽动力,这项驱动汽船和铁路的技术,通过为工厂提供动力并引发新的国家运输网络,推动了美国工业的崛起。“市场革命”重塑了这个国家。

The revolution reverberated across the country. More and more farmers grew crops for profit, not self-sufficiency. Vast factories and cities arose in the North. Enormous fortunes materialized. A new middle class ballooned. And as more men and women worked in the cash economy, they were freed from the bound dependence of servitude. But there were costs to this revolution. As northern textile factories boomed, the demand for southern cotton swelled, and American slavery accelerated. Northern subsistence farmers became laborers bound to the whims of markets and bosses. The market revolution sparked explosive economic growth and new personal wealth, but it also created a growing lower class of property-less workers and a series of devastating depressions, called “panics.” Many Americans labored for low wages and became trapped in endless cycles of poverty. Some workers, often immigrant women, worked thirteen hours a day, six days a week. Others labored in slavery. Massive northern textile mills turned southern cotton into cheap cloth. And although northern states washed their hands of slavery, their factories fueled the demand for slave-grown southern cotton and their banks provided the financing that ensured the profitability and continued existence of the American slave system. And so, as the economy advanced, the market revolution wrenched the United States in new directions as it became a nation of free labor and slavery, of wealth and inequality, and of endless promise and untold perils.

这场革命在全国各地产生了反响。越来越多的农民为了盈利而不是自给自足而种植作物。巨大的工厂和城市在北方兴起。巨额财富涌现。一个新的中产阶级迅速壮大。随着越来越多的男人和女人在现金经济中工作,他们从奴役的束缚中解放出来。但是这场革命也付出了代价。随着北方纺织厂的蓬勃发展,对南方棉花的需求膨胀,美国奴隶制加速发展。北方自给自足的农民变成了受市场和老板摆布的劳动者。市场革命引发了爆炸性的经济增长和新的个人财富,但也创造了一个不断壮大的无产阶级工人阶层,并引发了一系列被称为“恐慌”的毁灭性萧条。许多美国人为了微薄的工资而劳动,陷入了无休止的贫困循环。一些工人,通常是移民妇女,每天工作13个小时,每周工作6天。其他人则在奴隶制下劳动。北方的巨型纺织厂将南方棉花变成廉价布料。尽管北方各州洗脱了奴隶制的罪责,但它们的工厂却刺激了对奴隶种植的南方棉花的需求,而它们的银行则提供了资金,确保了美国奴隶制度的盈利能力和持续存在。因此,随着经济的发展,市场革命将美国推向了新的方向,使其成为一个自由劳动和奴隶制、财富和不平等、以及无尽的希望和不可言喻的危险并存的国家。

II. Early Republic Economic Development

三、早期共和国的经济发展

The growth of the American economy reshaped American life in the decades before the Civil War. Americans increasingly produced goods for sale, not for consumption. Improved transportation enabled a larger exchange network. Labor-saving technology improved efficiency and enabled the separation of the public and domestic spheres. The market revolution fulfilled the revolutionary generation’s expectations of progress but introduced troubling new trends. Class conflict, child labor, accelerated immigration, and the expansion of slavery followed. These strains required new family arrangements and transformed American cities.

在美国内战前的几十年里,美国经济的增长重塑了美国人的生活。美国人越来越多地生产用于销售的商品,而不是用于消费的商品。改进的交通促进了更大的交换网络。节省劳动力的技术提高了效率,并实现了公共领域和家庭领域的分离。市场革命实现了革命一代对进步的期望,但也引入了令人不安的新趋势。阶级冲突、童工、加速的移民和奴隶制的扩张接踵而至。这些压力需要新的家庭安排,并改变了美国城市。

American commerce had proceeded haltingly during the eighteenth century. American farmers increasingly exported foodstuffs to Europe as the French Revolutionary Wars devastated the continent between 1793 and 1815. America’s exports rose in value from $20.2 million in 1790 to $108.3 million by 1807. But while exports rose, exorbitant internal transportation costs hindered substantial economic development within the United States. In 1816, for instance, $9 could move one ton of goods across the Atlantic Ocean, but only thirty miles across land. An 1816 Senate Committee Report lamented that “the price of land carriage is too great” to allow the profitable production of American manufactures. But in the wake of the War of 1812, Americans rushed to build a new national infrastructure, new networks of roads, canals, and railroads. In his 1815 annual message to Congress, President James Madison stressed “the great importance of establishing throughout our country the roads and canals which can best be executed under national authority.” State governments continued to sponsor the greatest improvements in American transportation, but the federal government’s annual expenditures on internal improvements climbed to a yearly average of $1,323,000 by Andrew Jackson’s presidency.

在18世纪,美国的商业发展缓慢。由于1793年至1815年间法国革命战争摧毁了欧洲大陆,美国农民越来越多地向欧洲出口食品。美国的出口额从1790年的2020万美元增加到1807年的1.083亿美元。但是,尽管出口额上升,美国国内高昂的运输成本阻碍了美国国内的实质性经济发展。例如,1816年,9美元可以将一吨货物运过大西洋,但在陆地上只能运30英里。1816年参议院委员会报告感叹“陆路运输的价格太高”,无法使美国制造业实现盈利。但在1812年战争之后,美国人争先恐后地建立新的国家基础设施,新的道路、运河和铁路网络。詹姆斯·麦迪逊总统在1815年向国会发表的年度咨文中强调,“在全国范围内建立在国家权力下能够最好地执行的道路和运河具有重要意义”。各州政府继续资助美国交通方面的最大改进,但联邦政府在内部改进方面的年度支出在安德鲁·杰克逊总统任期内攀升至每年平均132.3万美元。

State legislatures meanwhile pumped capital into the economy by chartering banks. The number of state-chartered banks skyrocketed from 1 in 1783, 266 in 1820, and 702 in 1840 to 1,371 in 1860. European capital also helped build American infrastructure. By 1844, one British traveler declared that “the prosperity of America, her railroads, canals, steam navigation, and banks, are the fruit of English capital.”

与此同时,各州立法机构通过特许银行向经济注入资金。州特许银行的数量从1783年的1家猛增至1820年的266家,1840年的702家,到1860年达到1371家。欧洲资本也有助于建设美国的基础设施。到1844年,一位英国旅行家宣称,“美国的繁荣、铁路、运河、轮船航运和银行都是英国资本的成果。”

Economic growth, however, proceeded unevenly. Depressions devastated the economy in 1819, 1837, and 1857. Each followed rampant speculation in various commodities: land in 1819, land and enslaved laborers in 1837, and railroad bonds in 1857. Eventually the bubbles all burst. The spread of paper currency untethered the economy from the physical signifiers of wealth familiar to the colonial generation, namely land. Counterfeit bills were endemic during this early period of banking. With so many fake bills circulating, Americans were constantly on the lookout for the “confidence man” and other deceptive characters in the urban landscape. Con men and women could look like regular honest Americans. Advice literature offered young men and women strategies for avoiding hypocrisy in an attempt to restore the social fiber. Intimacy in the domestic sphere became more important as duplicity proliferated in the public sphere. Fear of the confidence man, counterfeit bills, and a pending bust created anxiety in the new capitalist economy. But Americans refused to blame the logic of their new commercial system for these depressions. Instead, they kept pushing “to get forward.”

然而,经济增长并非一帆风顺。1819年、1837年和1857年的经济萧条严重冲击了国家经济体系。这些萧条源自对不同商品的肆意投机:1819年的土地投机,1837年对土地和被奴役劳工的投机,以及1857年铁路债券市场的狂热投机。最终,这些经济泡沫相继破裂。纸币的广泛流通,使得经济脱离了殖民时代人们熟悉的财富实体标志——土地。在银行业发展的早期,伪造纸币问题十分猖獗。随着假钞的泛滥,美国人不得不时刻警惕城市中的“骗子”和其他形形色色的欺骗者。这些骗子往往伪装成普通而诚实的市民,令人防不胜防。劝诫类文学为年轻人提供了避免虚伪的建议,试图修复因欺诈行为而受损的社会纽带。随着欺诈在公共领域的蔓延,家庭生活中的亲密关系变得愈发重要。对骗子、假币以及即将到来的经济崩溃的恐惧,在新兴资本主义经济中引发了普遍的焦虑。然而,美国人并未将这些经济萧条归因于其新兴商业体系本身的逻辑。相反,他们始终坚持不懈地追求“向前迈进”。

The so-called Transportation Revolution opened the vast lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1810, before the rapid explosion of American infrastructure, Margaret Dwight left New Haven, Connecticut, in a wagon headed for Ohio Territory. Her trip was less than five hundred miles but took six weeks to complete. The journey was a terrible ordeal, she said. The roads were “so rocky & so gullied as to be almost impassable.” Ten days into the journey, at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, Dwight said “it appeared to me that we had come to the end of the habitable part of the globe.” She finally concluded that “the reason so few are willing to return from the Western country, is not that the country is so good, but because the journey is so bad.” Nineteen years later, in 1829, English traveler Frances Trollope made the reverse journey across the Allegheny Mountains from Cincinnati to the East Coast. At Wheeling, Virginia, her coach encountered the National Road, the first federally funded interstate infrastructure project. The road was smooth and her journey across the Alleghenies was a scenic delight. “I really can hardly conceive a higher enjoyment than a botanical tour among the Alleghany Mountains,” she declared. The ninety miles of the National Road was to her “a garden.”

所谓的“交通运输革命”打开了阿巴拉契亚山脉以西的广袤土地。1810年,在美国基础设施尚未迅速扩展之前,玛格丽特·德怀特从康涅狄格州纽黑文出发,乘坐一辆马车前往俄亥俄领地。她的旅程不到500英里,却花费了六周时间才完成。她称这段旅途是一场严酷的考验。道路“崎岖不平,沟壑纵横,几乎无法通行”。旅行十天后,在宾夕法尼亚州的伯利恒,德怀特说道:“在我看来,我们已经来到了地球上可居住的尽头。”她最终得出结论:“很少有人愿意从西部地区返回,并非因为那里有多好,而是因为旅途实在太糟糕了。”19年后,即1829年,英国旅行家弗朗西斯·特罗洛普完成了一次从辛辛那提前往东海岸的反向旅程,横跨了阿勒格尼山脉。在弗吉尼亚州惠灵,她的马车驶上了国家公路,这是一项由联邦政府资助的首个州际基础设施项目。公路平坦通畅,她穿越阿勒格尼山脉的旅途如诗如画,令人心旷神怡。“我真的很难想象还有什么比在阿勒格尼山脉进行植物学之旅更令人愉悦的,”她感叹道。对于她而言,全长90英里的国家公路简直就是“一个花园”。

If the two decades between Margaret Dwight’s and Frances Trollope’s journeys transformed the young nation, the pace of change only accelerated in the following years. If a transportation revolution began with improved road networks, it soon incorporated even greater improvements in the ways people and goods moved across the landscape.

如果说玛格丽特·德怀特和弗朗西斯·特罗洛普的旅行之间的二十年改变了这个年轻的国家,那么接下来的几年里,变化的步伐只会更加迅猛。如果交通运输革命是以改进的道路网络为起点,那么不久后,它便通过进一步改良人们和货物在陆地上的运输方式,带来了更深远的影响。

New York State completed the Erie Canal in 1825. The 350-mile-long human-made waterway linked the Great Lakes with the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean. Soon crops grown in the Great Lakes region were carried by water to eastern cities, and goods from emerging eastern factories made the reverse journey to midwestern farmers. The success of New York’s “artificial river” launched a canal-building boom. By 1840 Ohio created two navigable, all-water links from Lake Erie to the Ohio River.

纽约州于1825年建成了伊利运河。这条全长350英里的人工水道,将五大湖与哈德逊河及大西洋连接起来。不久之后,五大湖地区种植的农作物便通过水路源源不断地运往东部城市,而东部新兴工厂生产的商品则沿着相反的方向,输送到中西部的农民手中。纽约这条“人工河”的成功掀起了一股运河建设热潮。到1840年,俄亥俄州已经建成了两条全水路通道,连接了伊利湖和俄亥俄河,且均可通航。

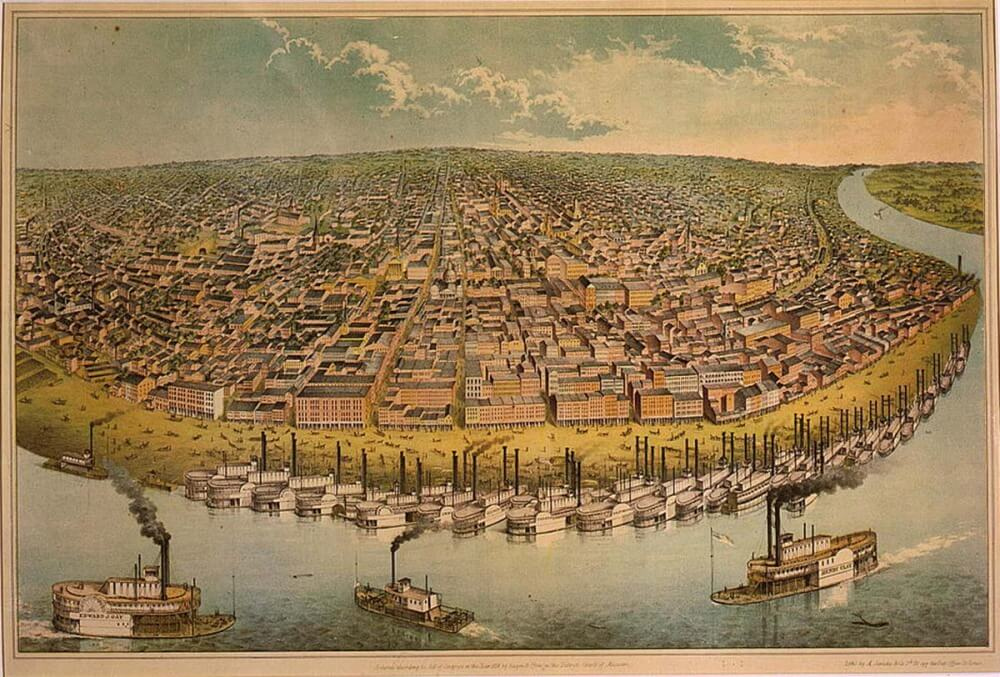

Robert Fulton established the first commercial steamboat service up and down the Hudson River in New York in 1807. Soon thereafter steamboats filled the waters of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers. Downstream-only routes became watery two-way highways. By 1830, more than two hundred steamboats moved up and down western rivers.

罗伯特·富尔顿于1807年在纽约的哈德逊河上开通了第一条商业轮船航线。不久之后,轮船便遍布密西西比河和俄亥俄河的水域。过去只能顺流而下的航线,变成了双向的水上高速通道。到1830年,西部河流上已有超过200艘轮船往来航行。

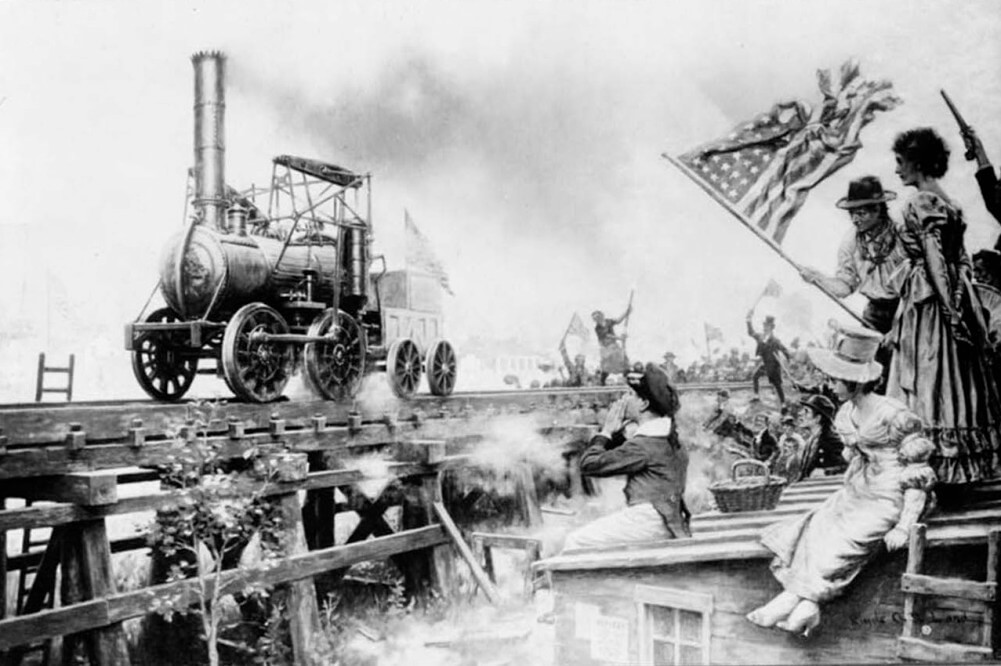

The United States’ first long-distance rail line launched from Maryland in 1827. Baltimore’s city government and the state government of Maryland provided half the start-up funds for the new Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Rail Road Company. The B&O’s founders imagined the line as a means to funnel the agricultural products of the trans-Appalachian West to an outlet on the Chesapeake Bay. Similar motivations led citizens in Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, and Charleston, South Carolina to launch their own rail lines. State and local governments provided the means for the bulk of this initial wave of railroad construction, but economic collapse following the Panic of 1837 made governments wary of such investments. Government supports continued throughout the century, but decades later the public origins of railroads were all but forgotten, and the railroad corporation became the most visible embodiment of corporate capitalism.

美国第一条长途铁路于1827年在马里兰州投入运营。巴尔的摩市政府和马里兰州政府为新的巴尔的摩和俄亥俄(B&O)铁路公司提供了一半的启动资金。B&O铁路的创始人设想,这条线路将成为把阿巴拉契亚山脉以西地区的农产品输送至切萨皮克湾出口的重要通道。出于类似的动机,费城、波士顿、纽约市和南卡罗来纳州的查尔斯顿也纷纷启动了自己的铁路建设计划。在这场最初的铁路建设浪潮中,州和地方政府提供了大部分资金支持。然而,1837年恐慌引发的经济崩溃,使得各级政府对此类投资变得更加谨慎。尽管如此,政府的支持贯穿整个19世纪。然而,几十年后,铁路的公共起源几乎被遗忘,而铁路公司却成为企业资本主义最显著的象征。

By 1860 Americans had laid more than thirty thousand miles of railroads. The ensuing web of rail, roads, and canals meant that few farmers in the Northeast or Midwest had trouble getting goods to urban markets. Railroad development was slower in the South, but there a combination of rail lines and navigable rivers meant that few cotton planters struggled to transport their products to textile mills in the Northeast and in England.

到1860年,美国已经铺设了超过三万英里的铁路。随之而来的铁路、公路和运河交织成网,使得东北部和中西部的农民在将货物运往城市市场时几乎不再遇到困难。南方的铁路发展相对较慢,但铁路与可通航河流的结合,确保了棉花种植者能顺利地将产品运送到东北部和英国的纺织厂。

Such internal improvements not only spread goods, they spread information. The transportation revolution was followed by a communications revolution. The telegraph redefined the limits of human communication. By 1843 Samuel Morse had persuaded Congress to fund a forty-mile telegraph line stretching from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. Within a few short years, during the Mexican-American War, telegraph lines carried news of battlefield events to eastern newspapers within days. This contrasts starkly with the War of 1812, when the Battle of New Orleans took place nearly two full weeks after Britain and the United States had signed a peace treaty.

这种内部基础设施的改善不仅促进了商品的流通,也推动了信息的传播。交通运输革命之后,通讯革命紧随其后。电报技术重新定义了人类交流的边界。到1843年,塞缪尔·莫尔斯成功说服国会资助修建一条从华盛顿特区到巴尔的摩的40英里电报线。在短短几年内,美墨战争期间,电报线将战场动态的新闻在几天内传递到了东部报纸。这一效率与1812年战争期间形成了鲜明对比——当时,新奥尔良战役发生时,英国和美国已签署和平条约近两周,但消息却迟迟未能传到。

The consequences of the transportation and communication revolutions reshaped the lives of Americans. Farmers who previously produced crops mostly for their own family now turned to the market. They earned cash for what they had previously consumed; they purchased the goods they had previously made or gone without. Market-based farmers soon accessed credit through eastern banks, which provided them with the opportunity to expand their enterprise but left also them prone before the risk of catastrophic failure wrought by distant market forces. In the Northeast and Midwest, where farm labor was ever in short supply, ambitious farmers invested in new technologies that promised to increase the productivity of the limited labor supply. The years between 1815 and 1850 witnessed an explosion of patents on agricultural technologies. The most famous of these, perhaps, was Cyrus McCormick’s horse-drawn mechanical reaper, which partially mechanized wheat harvesting, and John Deere’s steel-bladed plow, which more easily allowed for the conversion of unbroken ground into fertile farmland.

交通运输和通讯革命的影响重塑了美国人的生活。过去主要为自家生产农作物的农民,现在转向了面向市场的生产。他们将原本自用的农产品出售换取现金,用这些收入购买曾经需要自己动手制作或根本无法获得的商品。以市场为导向的农民很快通过东部的银行获得信贷,这为他们提供了扩大经营规模的机会,但同时也使他们暴露于遥远市场力量带来的灾难性失败风险之下。在劳动力长期短缺的东北部和中西部,雄心勃勃的农民开始投资新技术,这些技术承诺能提高有限劳动力的生产效率。1815年至1850年间,农业技术的专利数量激增。其中最著名的发明之一是塞勒斯·麦考密克的马拉机械收割机,它实现了小麦收割的部分机械化;另一项重要发明是约翰·迪尔的钢制犁,它大大简化了将未开垦土地转化为肥沃农田的过程。

Most visibly, the market revolution encouraged the growth of cities and reshaped the lives of urban workers. In 1820, only New York had over one hundred thousand inhabitants. By 1850, six American cities met that threshold, including Chicago, which had been founded fewer than two decades earlier. New technology and infrastructure paved the way for such growth. The Erie Canal captured the bulk of the trade emerging from the Great Lakes region, securing New York City’s position as the nation’s largest and most economically important city. The steamboat turned St. Louis and Cincinnati into centers of trade, and Chicago rose as it became the railroad hub of the western Great Lakes and Great Plains regions. The geographic center of the nation shifted westward. The development of steam power and the exploitation of Pennsylvania coalfields shifted the locus of American manufacturing. By the 1830s, for instance, New England was losing its competitive advantage to the West.

市场革命最显著的影响之一是推动了城市的增长,并重塑了城市工人的生活。1820年,全美只有纽约市的人口超过10万。然而到了1850年,包括芝加哥在内的六座城市达到了这一规模,而芝加哥的建城历史还不足二十年。新技术与基础设施的发展为这种快速增长奠定了基础。伊利运河吸纳了来自五大湖地区的大部分贸易,稳固了纽约市作为全美最大、经济最重要城市的地位。汽船的广泛应用使圣路易斯和辛辛那提发展为贸易中心,而芝加哥则凭借其成为西部五大湖和大平原地区的铁路枢纽而崛起。国家的地理重心逐步向西移动。与此同时,蒸汽动力的推广以及宾夕法尼亚煤田的开发,进一步改变了美国制造业的区域格局。例如,到19世纪30年代,新英格兰地区已经开始逐步丧失其原本在制造业中相较西部的竞争优势。

Meanwhile, the cash economy eclipsed the old, local, informal systems of barter and trade. Income became the measure of economic worth. Productivity and efficiencies paled before the measure of income. Cash facilitated new impersonal economic relationships and formalized new means of production. Young workers might simply earn wages, for instance, rather than receiving room and board and training as part of apprenticeships. Moreover, a new form of economic organization appeared: the business corporation.

与此同时,现金经济逐渐取代了传统的地方性、非正式的易货贸易体系。收入成为衡量经济价值的新标准,生产力和效率的重要性在收入面前黯然失色。现金的广泛使用催生了新的非个人化经济关系,并使生产方式趋于正规化。例如,年轻工人可能仅仅依靠赚取工资为生,而不再像学徒制那样以食宿和技能培训作为报酬。此外,一种全新的经济组织形式开始崭露头角:商业公司。

States offered the privileges of incorporation to protect the fortunes and liabilities of entrepreneurs who invested in early industrial endeavors. A corporate charter allowed investors and directors to avoid personal liability for company debts. The legal status of incorporation had been designed to confer privileges to organizations embarking on expensive projects explicitly designed for the public good, such as universities, municipalities, and major public works projects. The business corporation was something new. Many Americans distrusted these new, impersonal business organizations whose officers lacked personal responsibility while nevertheless carrying legal rights. Many wanted limits. Thomas Jefferson himself wrote in 1816 that “I hope we shall crush in its birth the aristocracy of our monied corporations which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength, and bid defiance to the laws of our country.” But in Dartmouth v. Woodward (1819) the Supreme Court upheld the rights of private corporations when it denied the attempt of the government of New Hampshire to reorganize Dartmouth College on behalf of the common good. Still, suspicions remained. A group of journeymen cordwainers in New Jersey publically declared in 1835 that they “entirely disapprov[ed] of the incorporation of Companies, for carrying on manual mechanical business, inasmuch as we believe their tendency is to eventuate and produce monopolies, thereby crippling the energies of individual enterprise.”

各州提供了公司特许的特权,以保护投资于早期工业企业的企业家的财富和负债。公司章程允许投资者和董事避免对公司债务承担个人责任。公司特许的法律地位旨在将特权赋予那些开展明确为公共利益而设计的昂贵项目的组织,例如大学、市政当局和重大公共工程项目。商业公司是新事物。许多美国人不信任这些新的、非个人的商业组织,这些组织的官员缺乏个人责任,但仍然享有法律权利。许多人希望加以限制。托马斯·杰斐逊本人在1816年写道,“我希望我们能够将那些已经敢于挑战我们的政府进行力量较量,并蔑视我们国家法律的货币公司的贵族势力扼杀在萌芽状态。”但在《达特茅斯诉伍德沃德案》(1819年)中,最高法院维护了私营公司的权利,当时它拒绝了新罕布什尔州政府为公共利益而重组达特茅斯学院的企图。不过,怀疑依然存在。新泽西州的一群熟练的鞋匠在1835年公开宣称,他们“完全不赞成将公司合并,以从事手工机械业务,因为我们相信它们的趋势是最终导致并产生垄断,从而削弱个人企业的活力。”

III. The Decline of Northern Slavery and the Rise of the Cotton Kingdom

三、北方奴隶制的衰落和棉花王国的崛起

Slave labor helped fuel the market revolution. By 1832, textile companies made up 88 out of 106 American corporations valued at over $100,000. These textile mills, worked by free labor, nevertheless depended on southern cotton, and the vast new market economy spurred the expansion of the plantation South.

奴隶劳动帮助推动了市场革命。到1832年,纺织公司占106家价值超过10万美元的美国公司中的88家。这些由自由劳动者工作的纺织厂仍然依赖于南方棉花,而庞大的新市场经济刺激了南方种植园的扩张。

By the early nineteenth century, states north of the Mason-Dixon Line had taken steps to abolish slavery. Vermont included abolition as a provision of its 1777 state constitution. Pennsylvania’s emancipation act of 1780 stipulated that freed children must serve an indenture term of twenty-eight years. Gradualism brought emancipation while also defending the interests of northern enslavers and controlling still another generation of Black Americans. In 1804 New Jersey became the last of the northern states to adopt gradual emancipation plans. There was no immediate moment of jubilee, as many northern states only promised to liberate future children born to enslaved mothers. Such laws also stipulated that such children remain in indentured servitude to their mother’s enslaver in order to compensate the enslaver’s loss. James Mars, a young man indentured under this system in Connecticut, risked being thrown in jail when he protested the arrangement that kept him bound to his mother’s enslaver until age twenty-five.

到19世纪初,梅森-狄克逊线以北的各州已经采取措施废除奴隶制。佛蒙特州在其1777年的州宪法中将废奴纳入其中。宾夕法尼亚州1780年的解放法案规定,被解放的儿童必须服役28年。渐进主义带来了解放,同时也维护了北方奴隶主的利益,并控制了另一代黑人美国人。1804年,新泽西州成为最后一个采取渐进解放计划的北方州。没有立即庆祝的时刻,因为许多北方州只是承诺解放未来出生于被奴役母亲的儿童。这些法律还规定,这些儿童应继续为他们母亲的奴隶主服役,以补偿奴隶主的损失。詹姆斯·马尔斯是康涅狄格州在此制度下被束缚的年轻人,当他抗议这种安排使他被束缚在他母亲的奴隶主手下直到25岁时,他冒着被投入监狱的风险。

Quicker routes to freedom included escape or direct emancipation by enslavers. But escape was dangerous and voluntary manumission rare. Congress, for instance, made the harboring of a freedom-seeking enslaved person a federal crime as early as 1793. Hopes for manumission were even slimmer, as few northern enslavers emancipated their own enslaved laborers. Roughly one fifth of the white families in New York City owned enslaved laborers, and fewer than eighty enslavers in the city voluntarily manumitted their enslaved laborers between 1783 and 1800. By 1830, census data suggests that at least 3,500 people were still enslaved in the North. Elderly enslaved people in Connecticut remained in bondage as late as 1848, and in New Jersey slavery endured until after the Civil War.

获得自由的更快途径包括逃跑或被奴隶主直接解放。但逃跑很危险,自愿解放也很罕见。例如,早在1793年,国会就将窝藏寻求自由的被奴役者定为联邦犯罪。解放的希望更加渺茫,因为很少有北方奴隶主解放自己的被奴役劳工。大约五分之一的纽约市白人家庭拥有被奴役的劳工,在1783年至1800年间,该市自愿解放被奴役劳工的奴隶主不到80人。到1830年,人口普查数据显示,北方至少仍有3500人被奴役。康涅狄格州年迈的被奴役者一直处于奴役状态,直到1848年,而在新泽西州,奴隶制一直持续到内战之后。

Emancipation proceeded slowly, but proceeded nonetheless. A free Black population of fewer than 60,000 in 1790 increased to more than 186,000 by 1810. Growing free Black communities fought for their civil rights. In a number of New England locales, free African Americans could vote and send their children to public schools. Most northern states granted Black citizens property rights and trial by jury. African Americans owned land and businesses, founded mutual aid societies, established churches, promoted education, developed print culture, and voted.

解放的进程虽然缓慢,但仍在继续。1790年,自由黑人人口不足6万人,到1810年增加到18.6万多人。不断壮大的自由黑人社区为他们的公民权利而战。在一些新英格兰地区,自由的非裔美国人可以投票并将他们的孩子送到公立学校。大多数北方州都赋予黑人公民财产权和陪审团审判权。非裔美国人拥有土地和企业,成立了互助协会,建立了教堂,促进了教育,发展了印刷文化并进行了投票。

Nationally, however, the enslaved population continued to grow, from less than 700,000 in 1790 to more than 1.5 million by 1820. The growth of abolition in the North and the acceleration of slavery in the South created growing divisions. Cotton drove the process more than any other crop. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin, a simple hand-cranked device designed to mechanically remove sticky green seeds from short staple cotton, allowed southern planters to dramatically expand cotton production for the national and international markets. Water-powered textile factories in England and the American Northeast rapidly turned raw cotton into cloth. Technology increased both the supply of and demand for cotton. White southerners responded by expanding cultivation farther west, to the Mississippi River and beyond. Slavery had been growing less profitable in tobacco-planting regions like Virginia, but the growth of cotton farther south and west increased the demand for human bondage. Eager cotton planters invested their new profits in more enslaved laborers.

然而,在全国范围内,被奴役的人口继续增长,从1790年的不足70万增加到1820年的150多万。北方废奴运动的兴起和南方奴隶制的加速发展造成了日益加剧的分裂。棉花比其他任何作物都更推动了这个进程。伊莱·惠特尼的轧棉机是一种简单的手摇装置,旨在机械地从短绒棉中去除粘稠的绿色种子,它使南方种植园主能够大幅扩大棉花产量,以满足国内和国际市场需求。英格兰和美国东北部的水力纺织厂迅速将原棉变成布料。技术增加了棉花的供应和需求。白人南方人通过向西扩张种植,向密西西比河及更远的地方扩张做出了回应。在弗吉尼亚州等烟草种植地区,奴隶制的盈利能力一直在下降,但南方和西部棉花的增长增加了对人类奴役的需求。渴望棉花种植者将他们的新利润投资于更多的被奴役劳工。

The cotton boom fueled speculation in slavery. Many enslavers leveraged potential profits into loans used to purchase ever increasing numbers of enslaved laborers. For example, one 1840 Louisiana Courier ad warned, “it is very difficult now to find persons willing to buy slaves from Mississippi or Alabama on account of the fears entertained that such property may be already mortgaged to the banks of the above named states.”

棉花繁荣刺激了对奴隶制的投机。许多奴隶主将潜在的利润转化为用于购买数量不断增加的被奴役劳工的贷款。例如,1840年《路易斯安那州信使报》的一则广告警告说,“现在很难找到愿意从密西西比州或阿拉巴马州购买奴隶的人,因为担心这些财产可能已经抵押给了上述各州的银行。”

New national and international markets fueled the plantation boom. American cotton exports rose from 150,000 bales in 1815 to 4,541,000 bales in 1859. The Census Bureau’s 1860 Census of Manufactures stated that “the manufacture of cotton constitutes the most striking feature of the industrial history of the last fifty years.” Enslavers shipped their cotton north to textile manufacturers and to northern financers for overseas shipments. Northern insurance brokers and exporters in the Northeast profited greatly.

新的国内和国际市场推动了种植园的繁荣。美国棉花出口量从1815年的15万包增加到1859年的454.1万包。人口普查局1860年《制造业人口普查》指出,“棉花制造业构成了过去五十年工业史上最引人注目的特征。”奴隶主将他们的棉花运往北方的纺织品制造商,并运给北方的金融家进行海外运输。东北部的北方保险经纪人和出口商获利颇丰。

While the United States ended its legal participation in the global slave trade in 1808, slave traders moved one million enslaved people from the tobacco-producing Upper South to cotton fields in the Lower South between 1790 and 1860. This harrowing trade in human flesh supported middle-class occupations in the North and South: bankers, doctors, lawyers, insurance brokers, and shipping agents all profited. And of course it facilitated the expansion of northeastern textile mills.

尽管美国在1808年停止了合法参与全球奴隶贸易,但在1790年至1860年间,奴隶贩子将约一百万名被奴役者从上南方的烟草种植区转移到下南方的棉花田。这场对人类肉体的残酷贸易支撑了北方和南方的中产阶级职业:银行家、医生、律师、保险经纪人以及航运代理人等都从中获利。当然,这也促进了东北部纺织厂的扩张。

IV. Changes in Labor Organization

四、劳工组织的变化

While industrialization bypassed most of the American South, southern cotton production nevertheless nurtured industrialization in the Northeast and Midwest. The drive to produce cloth transformed the American system of labor. In the early republic, laborers in manufacturing might typically have been expected to work at every stage of production. But a new system, piecework, divided much of production into discrete steps performed by different workers. In this new system, merchants or investors sent or “put out” materials to individuals and families to complete at home. These independent laborers then turned over the partially finished goods to the owner to be given to another laborer to finish.

尽管工业化绕过了美国南部的大部分地区,但南方棉花生产仍然促进了东北部和中西部的工业化。生产布料的动力改变了美国的劳动制度。在早期共和国时期,制造业的劳动者通常被期望参与生产的每一个阶段。但是一种新的制度,计件工资制,将大部分生产分成由不同的工人执行的离散步骤。在这个新的制度中,商人或投资者将材料发送或“外包”给个人和家庭,以便在家中完成。然后,这些独立的劳动者将部分完成的商品转交给所有者,再由所有者转交给另一名劳动者完成。

As early as the 1790s, however, merchants in New England began experimenting with machines to replace the putting-out system. To effect this transition, merchants and factory owners relied on the theft of British technological knowledge to build the machines they needed. In 1789, for instance, a textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, contracted twenty-one-year-old British immigrant Samuel Slater to build a yarn-spinning machine and then a carding machine. Slater had apprenticed in an English mill and succeeded in mimicking the English machinery. The fruits of American industrial espionage peaked in 1813 when Francis Cabot Lowell and Paul Moody re-created the powered loom used in the mills of Manchester, England. Lowell had spent two years in Britain observing and touring mills in England. He committed the design of the powered loom to memory so that, no matter how many times British customs officials searched his luggage, he could smuggle England’s industrial know-how into New England.

然而,早在1790年代,新英格兰的商人就开始尝试使用机器来取代外包制度。为了实现这一转变,商人和工厂主依靠窃取英国的技术知识来制造他们需要的机器。例如,1789年,罗得岛州波塔基特的一家纺织厂聘请了21岁的英国移民塞缪尔·斯莱特来制造一台纺纱机,然后又制造一台梳理机。斯莱特曾在一家英国工厂当学徒,并成功地模仿了英国的机械。美国工业间谍活动的成果在1813年达到顶峰,当时弗朗西斯·卡博特·洛厄尔和保罗·穆迪重新创造了英国曼彻斯特工厂中使用的动力织机。洛厄尔在英国花了两年时间观察和参观英国的工厂。他将动力织机的设计铭记于心,以便无论英国海关官员搜查他的行李多少次,他都可以将英国的工业技术偷偷带入新英格兰。

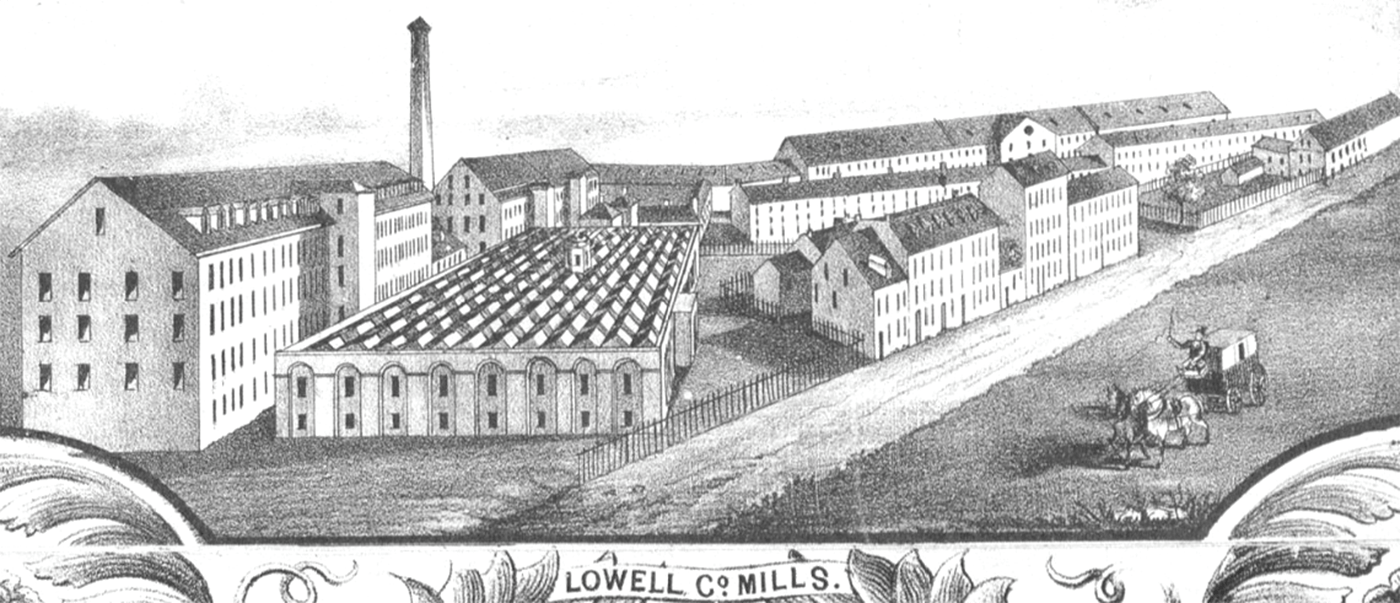

Lowell’s contribution to American industrialism was not only technological, it was organizational. He helped reorganize and centralize the American manufacturing process. A new approach, the Waltham-Lowell System, created the textile mill that defined antebellum New England and American industrialism before the Civil War. The modern American textile mill was fully realized in the planned mill town of Lowell in 1821, four years after Lowell himself died. Powered by the Merrimack River in northern Massachusetts and operated by local farm girls, the mills of Lowell centralized the process of textile manufacturing under one roof. The modern American factory was born. Soon ten thousand workers labored in Lowell alone. Sarah Rice, who worked at the nearby Millbury factory, found it “a noisy place” that was “more confined than I like to be.” Working conditions were harsh for the many desperate “mill girls” who operated the factories relentlessly from sunup to sundown. One worker complained that “a large class of females are, and have been, destined to a state of servitude.” Female workers went on strike. They lobbied for better working hours. But the lure of wages was too much. As another worker noted, “very many Ladies . . . have given up millinery, dressmaking & school keeping for work in the mill.” With a large supply of eager workers, Lowell’s vision brought a rush of capital and entrepreneurs into New England. The first American manufacturing boom was under way.

洛厄尔对美国工业化的贡献不仅是技术上的,也是组织上的。他帮助重组和集中了美国的制造过程。一种新方法,即沃尔瑟姆-洛厄尔系统,创建了定义内战前新英格兰和美国工业化的纺织厂。现代化的美国纺织厂于1821年在洛厄尔规划的工厂镇中完全实现,那是在洛厄尔本人去世四年后。由马萨诸塞州北部梅里马克河提供动力,并由当地的农场女孩经营,洛厄尔的工厂将纺织制造过程集中在一个屋檐下。现代化的美国工厂诞生了。很快,仅在洛厄尔就有1万名工人劳动。在附近米尔伯里工厂工作的莎拉·赖斯觉得这里是“一个嘈杂的地方”,而且“比我喜欢的要更受限制”。对于许多拼命工作的“工厂女孩”来说,工作条件很艰苦,她们每天从日出到日落都在工厂里不停地工作。一位工人抱怨说,“绝大多数女性注定要过着被奴役的生活”。女工们举行了罢工。她们游说争取更好的工作时间。但工资的诱惑太大了。正如另一位工人所指出的,“很多女士都放弃了女帽制作、服装制作和学校工作,转而到工厂工作。”随着大量渴望工作的工人出现,洛厄尔的愿景给新英格兰带来了大量的资本和企业家。美国第一次制造业繁荣正在进行中。

The market revolution shook other industries as well. Craftsmen began to understand that new markets increased the demand for their products. Some shoemakers, for instance, abandoned the traditional method of producing custom-built shoes at their home workshops and instead began producing larger quantities of shoes in ready-made sizes to be shipped to urban centers. Manufacturers wanting increased production abandoned the old personal approach of relying on a single live-in apprentice for labor and instead hired unskilled wage laborers who did not have to be trained in all aspects of making shoes but could simply be assigned a single repeatable aspect of the task. Factories slowly replaced shops. The old paternalistic apprentice system, which involved long-term obligations between apprentice and master, gave way to a more impersonal and more flexible labor system in which unskilled laborers could be hired and fired as the market dictated. A writer in the New York Observer in 1826 complained, “The master no longer lives among his apprentices [and] watches over their moral as well as mechanical improvement.” Masters-turned-employers now not only had fewer obligations to their workers, they had a lesser attachment. They no longer shared the bonds of their trade but were subsumed under new class-based relationships: employers and employees, bosses and workers, capitalists and laborers. On the other hand, workers were freed from the long-term, paternalistic obligations of apprenticeship or the legal subjugation of indentured servitude. They could theoretically work when and where they wanted. When men or women made an agreement with an employer to work for wages, they were “left free to apportion among themselves their respective shares, untrammeled . . . by unwise laws,” as Reverend Alonzo Potter rosily proclaimed in 1840. But while the new labor system was celebrated throughout the northern United States as “free labor,” it was simultaneously lamented by a growing powerless class of laborers.

市场革命也震撼了其他行业。工匠们开始意识到新市场增加了对其产品的需求。例如,一些鞋匠放弃了在自家作坊生产定制鞋的传统方法,而是开始生产大量现成的尺寸的鞋子,运往城市中心。希望提高产量的制造商放弃了依靠单一的住家学徒进行劳动的旧的个人方式,而是雇佣了无需接受所有制鞋培训的非熟练工资工人,他们可以简单地被分配到该任务的单一重复方面。工厂逐渐取代了商店。旧的家长式学徒制度,涉及学徒和师傅之间的长期义务,让位于一种更加非个人化和更灵活的劳动制度,在这种制度中,非熟练工人可以根据市场需求被雇用和解雇。一位《纽约观察家报》的作者在1826年抱怨说,“师傅不再与他的学徒住在一起,(并且)不再关注他们的道德和机械改进。”变成雇主的师傅现在不仅对他们的工人承担的义务减少了,而且他们的依恋也减少了。他们不再分享他们行业的纽带,而是被归入新的基于阶级的关系:雇主和雇员、老板和工人、资本家和劳动者。另一方面,工人从学徒的长期家长式义务或契约奴役的法律束缚中解放出来。理论上,他们可以在他们想工作的时间和地点工作。正如阿隆佐·波特牧师在1840年乐观地宣称的那样,当男人或女人与雇主达成协议以赚取工资时,他们“可以自由地在他们之间分配各自的份额,不受……不明智的法律的束缚”。但是,尽管新的劳动制度在整个美国北部被誉为“自由劳动”,但一个不断壮大的无权劳动阶层同时对此表示哀叹。

As the northern United States rushed headlong toward commercialization and an early capitalist economy, many Americans grew uneasy with the growing gap between wealthy businessmen and impoverished wage laborers. Elites like Daniel Webster might defend their wealth and privilege by insisting that all workers could achieve “a career of usefulness and enterprise” if they were “industrious and sober,” but labor activist Seth Luther countered that capitalism created “a cruel system of extraction on the bodies and minds of the producing classes . . . for no other object than to enable the ‘rich’ to ‘take care of themselves’ while the poor must work or starve.”

随着美国北部涌向商业化和早期的资本主义经济,许多美国人对富有的商人与贫困的工资劳动者之间日益扩大的差距感到不安。像丹尼尔·韦伯斯特这样的精英可能会通过坚持认为,如果所有工人“勤奋而清醒”,他们就可以实现“有用和有进取心的事业”来捍卫他们的财富和特权,但劳工活动家塞思·路德则反驳说,资本主义创造了一种“对生产阶级的身体和思想进行残酷剥削的制度……其唯一目的只是使‘富人’能够‘照顾好自己’,而穷人则必须工作或挨饿。”

Americans embarked on their Industrial Revolution with the expectation that all men could start their careers as humble wage workers but later achieve positions of ownership and stability with hard work. Wage work had traditionally been looked down on as a state of dependence, suitable only as a temporary waypoint for young men without resources on their path toward the middle class and the economic success necessary to support a wife and children ensconced within the domestic sphere. Children’s magazines—such as Juvenile Miscellany and Parley’s Magazine—glorified the prospect of moving up the economic ladder. This “free labor ideology” provided many northerners with a keen sense of superiority over the slave economy of the southern states.

美国人在开始工业革命时,怀着这样的期望:所有男性都能从卑微的工资工人起步,凭借努力工作最终获得所有权和稳定的地位。传统上,工资劳动被视为一种依赖状态,只适合作为没有资源的年轻人通向中产阶级的临时阶段,这种成功为他们提供了经济基础来支撑一个妻子和孩子,安稳地生活在家庭领域。儿童杂志——例如《少年杂记》和《帕利杂志》——大力推崇社会阶层上升的前景。这种“自由劳动意识形态”让许多北方人感到自己在经济上远远优于南方的奴隶制经济。

But the commercial economy often failed in its promise of social mobility. Depressions and downturns might destroy businesses and reduce owners to wage work. Even in times of prosperity unskilled workers might perpetually lack good wages and economic security and therefore had to forever depend on supplemental income from their wives and young children.

但是,商业经济常常未能实现其社会流动的承诺。萧条和经济衰退可能会摧毁企业并将所有者降为工资工作。即使在繁荣时期,非熟练工人也可能始终缺乏良好的工资和经济保障,因此必须永远依赖妻子和年幼的孩子的额外收入。

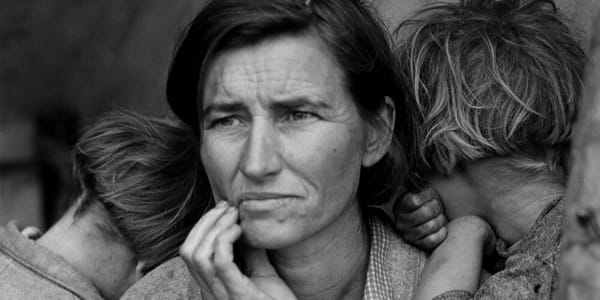

Wage workers—a population disproportionately composed of immigrants and poorer Americans—faced low wages, long hours, and dangerous working conditions. Class conflict developed. Instead of the formal inequality of a master-servant contract, employer and employee entered a contract presumably as equals. But hierarchy was evident: employers had financial security and political power; employees faced uncertainty and powerlessness in the workplace. Dependent on the whims of their employers, some workers turned to strikes and unions to pool their resources. In 1825 a group of journeymen in Boston formed a Carpenters’ Union to protest their inability “to maintain a family at the present time, with the wages which are now usually given.” Working men organized unions to assert themselves and win both the respect and the resources due to a breadwinner and a citizen.

蓝领工人——一个由移民和贫困美国人组成的比例过高的人口——面临着低工资、长时间工作和危险的工作条件。阶级冲突发展起来。雇主和雇员没有像主仆合同那样正式的不平等,而是以平等者的身份签订合同。但是等级制度显而易见:雇主拥有经济保障和政治权力;雇员在工作场所面临不确定性和无力感。由于依赖雇主的突发奇想,一些工人开始罢工和组建工会来集中他们的资源。1825年,波士顿的一群熟练工人成立了一个木匠工会,以抗议他们“目前无法以现在通常支付的工资维持一个家庭”。工人们组织工会来维护自己的权利,并赢得养家糊口者和公民应得的尊重和资源。

For the middle-class managers and civic leaders caught between workers and owners, unions enflamed a dangerous antagonism between employers and employees. They countered any claims of inherent class conflict with the ideology of social mobility. Middle-class owners and managers justified their economic privilege as the natural product of superior character traits, including decision making and hard work. One group of master carpenters denounced their striking journeymen in 1825 with the claim that workers of “industrious and temperate habits, have, in their turn, become thriving and respectable Masters, and the great body of our Mechanics have been enabled to acquire property and respectability, with a just weight and influence in society.” In an 1856 speech in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Abraham Lincoln had to assure his audience that the country’s commercial transformation had not reduced American laborers to slavery. Southerners, he said, “insist that their slaves are far better off than Northern freemen. What a mistaken view do these men have of Northern labourers! They think that men are always to remain labourers here—but there is no such class. The man who laboured for another last year, this year labours for himself. And next year he will hire others to labour for him.” This essential belief undergirded the northern commitment to “free labor” and won the market revolution much widespread acceptance.

对于夹在工人和业主之间的中产阶级管理人员和公民领袖来说,工会加剧了雇主和雇员之间危险的对抗。他们以社会流动的意识形态来反驳任何固有的阶级冲突的主张。中产阶级业主和管理人员将他们的经济特权合理化为卓越性格特征(包括决策和勤奋工作)的自然产物。一群木匠师傅在1825年谴责他们罢工的熟练工人,声称那些“勤奋和节俭习惯的工人,已经轮流成为繁荣和受人尊敬的师傅,我们的大部分机械师都能够获得财产和体面,并在社会中拥有公正的份量和影响力。”在1856年密歇根州卡拉马祖的一次演讲中,亚伯拉罕·林肯不得不向他的听众保证,该国的商业转型并没有将美国劳动者降低为奴隶。他说,南方人“坚持认为他们的奴隶比北方自由人过得好得多。这些人对北方劳动者有什么误解啊!他们认为这里的人永远都会是劳动者——但没有这样的阶级。去年为别人劳动的人,今年为自己劳动。明年他将雇用其他人为他劳动。”这种基本的信念支撑了北方人对“自由劳动”的承诺,并为市场革命赢得了广泛的认可。

V. Changes in Gender Roles and Family Life

五、性别角色和家庭生活的变化

In the first half of the nineteenth century, families in the northern United States increasingly participated in the cash economy created by the market revolution. The first stirrings of industrialization shifted work away from the home. These changes transformed Americans’ notions of what constituted work and therefore shifted what it meant to be an American woman and an American man. As Americans encountered more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the ability to remove women and children from work determined a family’s class status. This ideal, of course, ignored the reality of women’s work at home and was possible for only the wealthy. The market revolution therefore not only transformed the economy, it changed the nature of the American family. As the market revolution thrust workers into new systems of production, it redefined gender roles. The market integrated families into a new cash economy. As Americans purchased more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the purity of the domestic sphere—the idealized realm of women and children—increasingly signified a family’s class status.

在19世纪上半叶,美国北方的家庭越来越多地参与了市场革命创造的现金经济。工业化的最初萌芽将工作从家庭转移出去。这些变化改变了美国人对构成工作的概念,并因此改变了成为美国女性和美国男性的意义。随着美国人在商店里遇到更多的商品,而在家里生产的商品减少,将妇女和儿童从工作中解放出来的能力决定了一个家庭的阶级地位。当然,这种理想忽视了妇女在家工作的现实,而且只有富人才能实现。因此,市场革命不仅改变了经济,还改变了美国大家庭的性质。随着市场革命将工人推向新的生产体系,它重新定义了性别角色。市场将家庭融入了新的现金经济中。随着美国人在商店里购买更多的商品,而在家里生产的商品减少,家庭领域的纯洁性——女性和儿童的理想领域——越来越象征着一个家庭的阶级地位。

Women and children worked to supplement the low wages of many male workers. Around age eleven or twelve, boys could take jobs as office runners or waiters, earning perhaps a dollar a week to support their parents’ incomes. The ideal of an innocent and protected childhood was a privilege for middle- and upper-class families, who might look down upon poor families. Joseph Tuckerman, a Unitarian minister who served poor Bostonians, lamented the lack of discipline and regularity among poor children: “At one hour they are kept at work to procure fuel, or perform some other service; in the next are allowed to go where they will, and to do what they will.” Prevented from attending school, poor children served instead as economic assets for their destitute families.

妇女和儿童努力补充许多男性工人的低工资。大约在11或12岁时,男孩可以担任办公室跑腿或服务员的工作,每周赚大约一美元来支持父母的收入。无辜和受保护的童年理想是中上阶级家庭的特权,他们可能会看不起贫困家庭。为波士顿穷人服务的统一主义牧师约瑟夫·塔克曼对贫困儿童缺乏纪律和规律感到遗憾:“他们一会儿被要求工作以获取燃料或执行其他服务;下一刻则被允许随心所欲地去任何地方,做他们想做的事。”由于无法上学,贫困儿童反而成为他们贫困家庭的经济资产。

Meanwhile, the education received by middle-class children provided a foundation for future economic privilege. As artisans lost control over their trades, young men had a greater incentive to invest time in education to find skilled positions later in life. Formal schooling was especially important for young men who desired apprenticeships in retail or commercial work. Enterprising instructors established schools to assist “young gentlemen preparing for mercantile and other pursuits, who may wish for an education superior to that usually obtained in the common schools, but different from a college education, and better adapted to their particular business,” such as that organized in 1820 by Warren Colburn of Boston. In response to this need, the Boston School Committee created the English High School (as opposed to the Latin School) that could “give a child an education that shall fit him for active life, and shall serve as a foundation for eminence in his profession, whether Mercantile or Mechanical” beyond that “which our public schools can now furnish.”

与此同时,中产阶级儿童接受的教育为未来的经济特权奠定了基础。随着工匠们失去了对其行业的控制,年轻人更有动力投入时间在教育上,以便在以后的生活中找到熟练的职位。对于渴望从事零售或商业工作的年轻人来说,正规教育尤其重要。积极进取的教师创办学校,以帮助“准备从事商业和其他职业的年轻人,他们可能希望获得比普通学校通常获得的教育更高,但不同于大学教育,并且更适合其特定业务的教育”,例如波士顿的沃伦·科尔本在1820年组织的教育。为了满足这种需求,波士顿学校委员会创建了英语高中(相对于拉丁语学校),该高中可以“为孩子提供一种让他适合积极生活的教育,并为他在商业或机械方面的卓越成就奠定基础”,这超出了“我们公立学校现在能够提供的范围”。

Education equipped young women with the tools to live sophisticated, genteel lives. After sixteen-year-old Elizabeth Davis left home in 1816 to attend school, her father explained that the experience would “lay a foundation for your future character & respectability.” After touring the United States in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville praised the independence granted to the young American woman, who had “the great scene of the world . . . open to her” and whose education prepared her to exercise both reason and moral sense. Middling young women also used their education to take positions as schoolteachers in the expanding common school system. Bristol Academy in Taunton, Massachusetts, for instance, advertised “instruction . . . in the art of teaching” for female pupils. In 1825, Nancy Denison left Concord Academy with references indicating that she was “qualified to teach with success and profit” and “very cheerfully recommend[ed]” for “that very responsible employment.”

教育使年轻女性具备了过上精致、优雅生活的工具。16岁的伊丽莎白·戴维斯于1816年离开家去上学后,她的父亲解释说,这段经历将“为你的未来品格和体面奠定基础”。在1830年代游览美国后,亚历克西斯·德·托克维尔赞扬了给予美国年轻女性的独立性,她们“拥有广阔的世界……向她敞开”,她们的教育使她能够运用理性和道德感。中产阶级的年轻女性也利用她们的教育在不断扩大的普通学校系统中担任教师职位。例如,马萨诸塞州汤顿的布里斯托尔学院为女学生提供“教学艺术方面的指导”。1825年,南希·丹尼森离开了康科德学院,她的推荐信表明她“有资格成功且有利可图地教学”,并且“非常愉快地推荐(她)”从事“这项非常负责任的职业”。

Middle-class youths found opportunities for respectable employment through formal education, but poor youths remained in marginalized positions. Their families’ desperate financial state kept them from enjoying the fruits of education. When pauper children did receive teaching through institutions such as the House of Refuge in New York City, they were often simultaneously indentured to successful families to serve as field hands or domestic laborers. The Society for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents in New York City sent its wards to places like Sylvester Lusk’s farm in Enfield, Connecticut. Lusk took boys to learn “the trade and mystery of farming” and girls to learn “the trade and mystery of housewifery.” In exchange for “sufficient Meat, Drink, Apparel, Lodging, and Washing, fitting for an Apprentice,” and a rudimentary education, the apprentices promised obedience, morality, and loyalty. Poor children also found work in factories such as Samuel Slater’s textile mills in southern New England. Slater published a newspaper advertisement for “four or five active Lads, about 15 Years of Age to serve as Apprentices in the Cotton Factory.”

中产阶级的年轻人通过正规教育找到了从事体面工作的机会,但贫困的年轻人仍然处于边缘化的地位。他们家庭的绝望财务状况使他们无法享受教育的成果。当贫困儿童通过纽约市的避难所等机构接受教育时,他们通常同时被契约给成功的家庭,充当田地帮手或家政工人。纽约市少年犯改革协会将其监护人送往康涅狄格州恩菲尔德的西尔维斯特·拉斯克农场等地。拉斯克带男孩去学习“农业的行业和奥秘”,带女孩去学习“家政的行业和奥秘”。为了换取“足以胜任学徒的肉、饮料、服装、住宿和洗衣”,以及基础教育,学徒们承诺服从、道德和忠诚。贫困的儿童还在南方新英格兰塞缪尔·斯莱特的纺织厂等工厂找到了工作。斯莱特在报纸上刊登广告,招收“四五个15岁左右的活跃男孩,在棉花厂担任学徒”。

And so, during the early nineteenth century, opportunities for education and employment often depended on a given family’s class. In colonial America, nearly all children worked within their parent’s chosen profession, whether it be agricultural or artisanal. During the market revolution, however, more children were able to postpone employment. Americans aspired to provide a “Romantic Childhood”—a period in which boys and girls were sheltered within the home and nurtured through primary schooling. This ideal was available to families that could survive without their children’s labor. As these children matured, their early experiences often determined whether they entered respectable, well-paying positions or became dependent workers with little prospects for social mobility.

因此,在19世纪初,受教育和就业的机会通常取决于特定家庭的阶级。在殖民时期的美国,几乎所有的孩子都在其父母选择的职业中工作,无论是农业还是手工业。然而,在市场革命期间,更多的孩子能够推迟就业。美国人渴望提供一个“浪漫的童年”——一个男孩和女孩被庇护在家里,并通过小学教育得到培养的时期。这种理想适用于那些无需孩子劳动也能生存的家庭。随着这些孩子的成熟,他们早期的经历通常决定了他们是进入体面、高薪的职位,还是成为社会流动性前景渺茫的依赖工人。

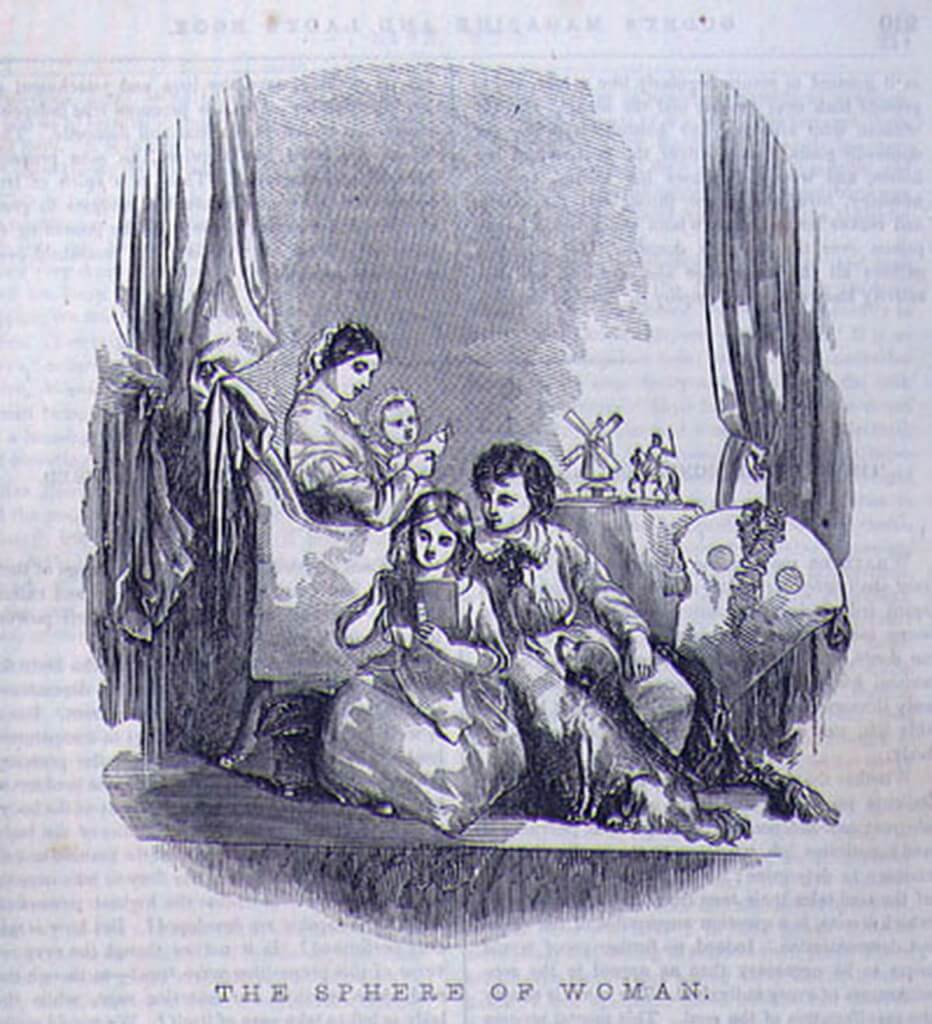

Just as children were expected to be sheltered from the adult world of work, American culture expected men and women to assume distinct gender roles as they prepared for marriage and family life. An ideology of “separate spheres” set the public realm—the world of economic production and political life—apart as a male domain, and the world of consumers and domestic life as a female one. (Even nonworking women labored by shopping for the household, producing food and clothing, cleaning, educating children, and performing similar activities. But these were considered “domestic” because they did not bring money into the household, although they too were essential to the household’s economic viability.) While reality muddied the ideal, the divide between a private, female world of home and a public, male world of business defined American gender hierarchy.

正如人们期望孩子们远离成年人的工作世界一样,美国文化期望男人和女人在准备结婚和家庭生活时承担不同的性别角色。“分立领域”的思想将公共领域——经济生产和政治生活的世界——视为男性领域,而将消费者和家庭生活的世界视为女性领域。(即使是不工作的妇女也通过为家庭购物、生产食物和衣服、清洁、教育孩子以及执行类似活动来劳动。但这些被认为是“家庭的”,因为它们没有给家庭带来收入,尽管它们对于家庭的经济生存能力也至关重要。)尽管现实模糊了理想,但私人、女性的家庭世界和公共、男性的商业世界之间的鸿沟定义了美国的性别等级制度。

The idea of separate spheres also displayed a distinct class bias. Middle and upper classes reinforced their status by shielding “their” women from the harsh realities of wage labor. Women were to be mothers and educators, not partners in production. But lower-class women continued to contribute directly to the household economy. The middle- and upper-class ideal was feasible only in households where women did not need to engage in paid labor. In poorer households, women engaged in wage labor as factory workers, pieceworkers producing items for market consumption, tavern- and innkeepers, and domestic servants. While many of the fundamental tasks women performed remained the same—producing clothing, cultivating vegetables, overseeing dairy production, and performing any number of other domestic labors—the key difference was whether and when they performed these tasks for cash in a market economy.

分立领域的概念也显示出明显的阶级偏见。中产阶级和上层阶级通过保护“他们的”妇女免受工资劳动的残酷现实来巩固他们的地位。妇女应该是母亲和教育者,而不是生产的伙伴。但下层阶级的妇女继续为家庭经济做出直接贡献。中上层阶级的理想只有在妇女不需要从事有偿劳动力的家庭中才是可行的。在较贫困的家庭中,妇女从事工资劳动,担任工厂工人、生产用于市场消费的物品的计件工人、酒馆和旅馆老板以及家庭佣人。虽然妇女所做的许多基本工作仍然相同——生产衣服、种植蔬菜、监督乳制品生产以及执行许多其他家务劳动——但关键的区别在于她们是否以及何时在市场经济中为现金执行这些任务。

Domestic expectations constantly changed and the market revolution transformed many women’s traditional domestic tasks. Cloth production, for instance, advanced throughout the market revolution as new mechanized production increased the volume and variety of fabrics available to ordinary people. This relieved many better-off women of a traditional labor obligation. As cloth production became commercialized, women’s home-based cloth production became less important to household economies. Purchasing cloth and, later, ready-made clothes began to transform women from producers to consumers. One woman from Maine, Martha Ballard, regularly referenced spinning, weaving, and knitting in the diary she kept from 1785 to 1812. Martha, her daughters, and her female neighbors spun and plied linen and woolen yarns and used them to produce a variety of fabrics to make clothing for her family. The production of cloth and clothing was a year-round, labor-intensive process, but it was for home consumption, not commercial markets.

家庭期望不断变化,市场革命改变了许多妇女的传统家庭任务。例如,随着新的机械化生产增加了普通人可获得的织物的数量和种类,在整个市场革命期间,布料生产得到了发展。这减轻了许多较富裕的妇女的传统劳动义务。随着布料生产的商业化,妇女以家庭为基础的布料生产对家庭经济变得不那么重要了。购买布料,以及后来的成品衣服,开始将妇女从生产者转变为消费者。来自缅因州的一位妇女玛莎·巴拉德在她1785年至1812年期间写的日记中经常提到纺纱、织布和编织。玛莎、她的女儿和她女性邻居纺织和编织亚麻和羊毛纱线,并用它们来制作各种织物,为她的家人制作衣服。布料和衣服的生产是一个全年、劳动密集型的过程,但它是为了家庭消费,而不是商业市场。

In cities, where women could buy cheap imported cloth to turn into clothing, they became skilled consumers. They stewarded money earned by their husbands by comparing values and haggling over prices. In one typical experience, Mrs. Peter Simon, a captain’s wife, inspected twenty-six yards of Holland cloth to ensure that it was worth the £130 price. Even wealthy women shopped for high-value goods. While servants or enslaved people routinely made low-value purchases, the mistress of the household trusted her discriminating eye alone for expensive or specific purchases.

在城市里,妇女可以购买廉价的进口布料来制作衣服,她们成了熟练的消费者。她们通过比较价值和讨价还价来管理丈夫赚来的钱。在一个典型的经历中,一位船长的妻子彼得·西蒙夫人检查了26码的荷兰布,以确保其价值130英镑。即使是富有的女性也会购买高价值的商品。虽然仆人或被奴役的人经常购买低价值的商品,但家庭的女主人只相信她自己精明的眼光来购买昂贵或特定的商品。

Women might also parlay their skills into businesses. In addition to working as seamstresses, milliners, or laundresses, women might undertake paid work for neighbors or acquaintances or combine clothing production with management of a boardinghouse. Even enslaved laborers with particular skill at producing clothing could be hired out for a higher price or might even negotiate to work part-time for themselves. Most enslaved people, however, continued to produce domestic items, including simpler cloths and clothing, for home consumption.

妇女也可以将她们的技能转化为企业。除了担任女裁缝、女帽制造商或洗衣妇外,妇女还可以为邻居或熟人从事有偿工作,或将服装生产与管理寄宿公寓结合起来。即使是有特定服装生产技能的被奴役劳工也可以以更高的价格被雇用,甚至可以谈判为自己兼职工作。然而,大多数被奴役的人继续生产包括较简单的布料和衣服在内的家庭用品,供家庭消费。

Similar domestic expectations played out in the slave states. Enslaved women labored in the fields. Whites argued that African American women were less delicate and womanly than white women and therefore perfectly suited for agricultural labor. The southern ideal meanwhile established that white plantation mistresses were shielded from manual labor because of their very whiteness. Throughout the slave states, however, aside from the minority of plantations with dozens of enslaved laborers, most white women by necessity continued to assist with planting, harvesting, and processing agricultural projects despite the cultural stigma attached to it. White southerners continued to produce large portions of their food and clothing at home. Even when they were market-oriented producers of cash crops, white southerners still insisted that their adherence to plantation slavery and racial hierarchy made them morally superior to greedy northerners and their callous, cutthroat commerce. Southerners and northerners increasingly saw their ways of life as incompatible.

在奴隶制各州,类似的家庭期望也得到了体现。被奴役的妇女在田里劳动。白人认为,非裔美国妇女不如白人妇女那样娇弱和女人味,因此非常适合农业劳动。与此同时,南方的理想规定,白人种植园女主人因其白人身份而免受体力劳动。然而,在整个奴隶制各州,除了少数拥有数十名被奴役劳工的种植园外,大多数白人妇女迫于必要继续协助种植、收割和加工农业项目,尽管这在文化上带有污名。白人南方人继续在家里生产大部分食物和衣服。即使他们是以市场为导向的经济作物生产者,白人南方人仍然坚持认为,他们对种植园奴隶制和种族等级制度的坚持使他们在道德上优于贪婪的北方人及其冷酷无情的商业行为。南方人和北方人越来越认为他们的生活方式不相容。

While the market revolution remade many women’s economic roles, their legal status remained essentially unchanged. Upon marriage, women were rendered legally dead by the notion of coverture, the custom that counted married couples as a single unit represented by the husband. Without special precautions or interventions, women could not earn their own money, own their own property, sue, or be sued. Any money earned or spent belonged by law to their husbands. Women shopped on their husbands’ credit and at any time husbands could terminate their wives’ access to their credit. Although a handful of states made divorce available—divorce had before only been legal in Congregationalist states such as Massachusetts and Connecticut, where marriage was strictly a civil contract rather than a religious one—it remained extremely expensive, difficult, and rare. Marriage was typically a permanently binding legal contract.

虽然市场革命改变了许多妇女的经济角色,但她们的法律地位基本保持不变。结婚后,由于“覆盖权”的概念,妇女在法律上被判为死亡,该习俗将已婚夫妇视为由丈夫代表的单一单位。如果没有特别的预防措施或干预,妇女就无法赚自己的钱、拥有自己的财产、起诉或被起诉。任何赚取或花费的钱都依法属于她们的丈夫。妇女用丈夫的信用购物,丈夫可以随时终止妻子使用其信用的权利。尽管少数几个州允许离婚——以前离婚只在马萨诸塞州和康涅狄格州等公理会州是合法的,在这些州,婚姻严格来说是一种民事合同而不是宗教合同——但离婚仍然非常昂贵、困难且罕见。婚姻通常是一份永久性的具有约束力的法律合同。

Ideas of marriage, if not the legal realities, began to change. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth century marked the beginning of the shift from “institutional” to “companionate” marriage. Institutional marriages were primarily labor arrangements that maximized the couple’s and their children’s chances of surviving and thriving. Men and women assessed each other’s skills as they related to household production, although looks and personality certainly entered into the equation. But in the late eighteenth century, under the influence of Enlightenment thought, young people began to privilege character and compatibility in their potential partners. Money was still essential: marriages prompted the largest redistributions of property prior to the settling of estates at death. But the means of this redistribution was changing. Especially in the North, land became a less important foundation for matchmaking as wealthy young men became not only farmers and merchants but bankers, clerks, or professionals. The increased emphasis on affection and attraction that young people embraced was facilitated by an increasingly complex economy that offered new ways to store, move, and create wealth, which liberalized the criteria by which families evaluated potential in-laws.

关于婚姻的观念(如果不是法律现实)开始发生变化。18世纪末和19世纪初标志着从“制度性”婚姻向“伴侣式”婚姻转变的开始。制度性婚姻主要是劳动安排,旨在最大限度地提高夫妇及其子女的生存和繁荣的机会。男人和女人评估彼此与家庭生产相关的技能,尽管外貌和个性肯定也考虑在内。但在18世纪末,在启蒙思想的影响下,年轻人开始重视潜在伴侣的性格和相容性。金钱仍然至关重要:婚姻促成了在死后结算遗产之前最大的财产再分配。但这种再分配的方式正在发生变化。尤其是在北方,随着富有的年轻人不仅成为农民和商人,而且成为银行家、职员或专业人士,土地在婚姻中变得不那么重要了。年轻人所接受的对情感和吸引力的日益重视,得益于日益复杂的经济体系,该体系提供了新的储存、转移和创造财富的方式,从而放宽了家庭评估未来姻亲的标准。

To be considered a success in family life, a middle-class American man typically aspired to own a comfortable home and to marry a woman of strong morals and religious conviction who would take responsibility for raising virtuous, well-behaved children. The duties of the middle-class husband and wife would be clearly delineated into separate spheres. The husband alone was responsible for creating wealth and engaging in the commerce and politics—the public sphere. The wife was responsible for the private—keeping a good home, being careful with household expenses, and raising children, inculcating them with the middle-class virtues that would ensure their future success. But for poor families, sacrificing the potential economic contributions of wives and children was an impossibility.

为了在家庭生活中取得成功,一个中产阶级的美国男人通常渴望拥有舒适的家,并娶一个具有强烈道德和宗教信仰的女人为妻,她将负责养育有美德、行为良好的孩子。中产阶级丈夫和妻子的职责将明确划分为不同的领域。丈夫独自负责创造财富并从事商业和政治——公共领域。妻子则负责私人领域——保持良好的家庭环境、谨慎处理家庭开支以及养育孩子,向他们灌输中产阶级的品德,这将确保他们未来的成功。但对于贫困家庭来说,牺牲妻子和孩子潜在的经济贡献是不可能的。

VI. The Rise of Industrial Labor in Antebellum America

六、内战前美国工业劳工的兴起

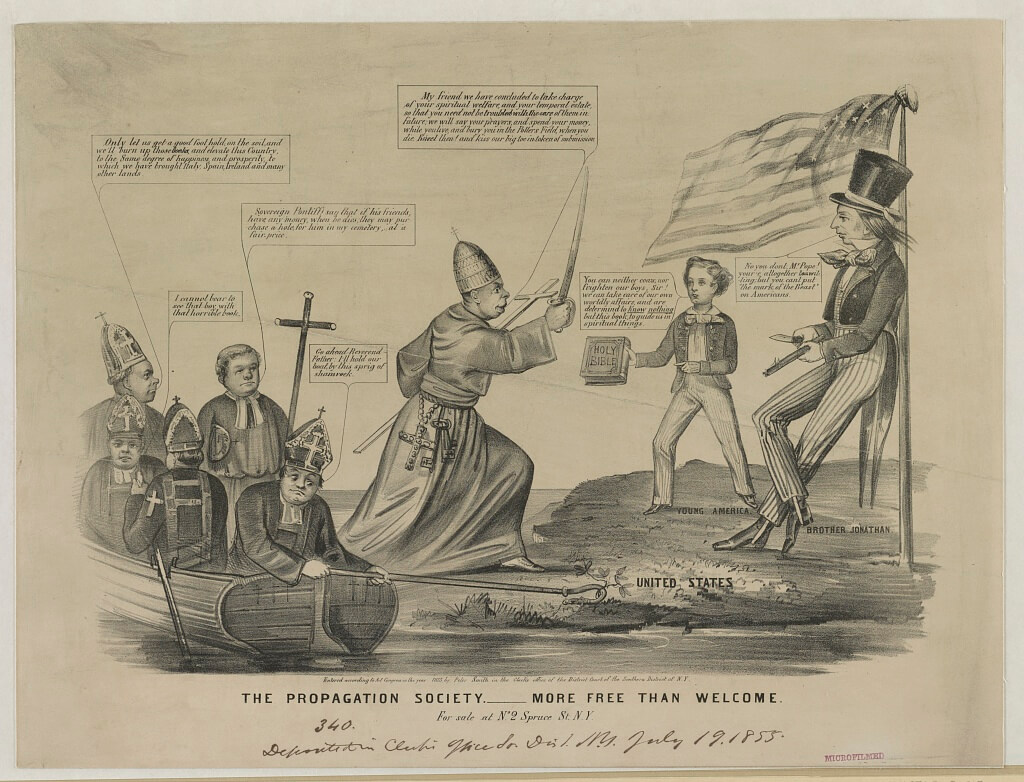

More than five million immigrants arrived in the United States between 1820 and 1860. Irish, German, and Jewish immigrants sought new lives and economic opportunities. By the Civil War, nearly one out of every eight Americans had been born outside the United States. A series of push and pull factors drew immigrants to the United States.

1820年至1860年间,有500多万移民抵达美国。爱尔兰、德国和犹太移民寻求新的生活和经济机会。到内战时,几乎每八个美国人中就有一个出生在美国境外。许多因素促使移民选择来到美国,其中包括在本国的困境以及美国提供的机会。

In England, an economic slump prompted Parliament to modernize British agriculture by revoking common land rights for Irish farmers. These policies generally targeted Catholics in the southern counties of Ireland and motivated many to seek greater opportunity elsewhere. The booming American economy pulled Irish immigrants toward ports along the eastern United States. Between 1820 and 1840, over 250,000 Irish immigrants arrived in the United States. Without the capital and skills required to purchase and operate farms, Irish immigrants settled primarily in northeastern cities and towns and performed unskilled work. Irish men usually emigrated alone and, when possible, practiced what became known as chain migration. Chain migration allowed Irish men to send portions of their wages home, which would then be used either to support their families in Ireland or to purchase tickets for relatives to come to the United States. Irish immigration followed this pattern into the 1840s and 1850s, when the infamous Irish Famine sparked a massive exodus out of Ireland. Between 1840 and 1860, 1.7 million Irish fled starvation and the oppressive English policies that accompanied it. As they entered manual, unskilled labor positions in urban America’s dirtiest and most dangerous occupations, Irish workers in northern cities were compared to African Americans, and anti-immigrant newspapers portrayed them with apelike features. Despite hostility, Irish immigrants retained their social, cultural, and religious beliefs and left an indelible mark on American culture.

在英国,经济衰退促使议会通过撤销爱尔兰农民的共同土地权来使英国农业现代化。这些政策通常针对爱尔兰南部各县的天主教徒,并促使许多人到其他地方寻求更大的机会。蓬勃发展的美国经济将爱尔兰移民吸引到美国东部的港口。1820年至1840年间,有超过25万爱尔兰移民抵达美国。由于缺乏购买和经营农场所需的资本和技能,爱尔兰移民主要定居在东北部的城镇和城市,并从事非熟练工作。爱尔兰男子通常独自移民,并在可能的情况下,实行被称为链式移民的制度。链式移民使爱尔兰男子能够将部分工资寄回家,这些工资随后将被用来支持他们在爱尔兰的家人或购买亲戚来美国的机票。1840年代和1850年代,爱尔兰移民遵循了这种模式,当时臭名昭著的爱尔兰饥荒引发了爱尔兰的大规模外流。1840年至1860年间,有170万爱尔兰人逃离了饥荒和随之而来的压迫性英国政策。当他们进入美国城市最肮脏和最危险的职业中的体力劳动、非熟练职位时,北方城市的爱尔兰工人被比作非裔美国人,反移民报纸将他们描绘成猿猴般的特征。尽管遭到敌视,爱尔兰移民仍然保留了他们的社会、文化和宗教信仰,并在美国文化中留下了不可磨灭的印记。

While the Irish settled mostly in coastal cities, most German immigrants used American ports and cities as temporary waypoints before settling in the rural countryside. Over 1.5 million immigrants from the various German states arrived in the United States during the antebellum era. Although some southern Germans fled declining agricultural conditions and repercussions of the failed revolutions of 1848, many Germans simply sought steadier economic opportunity. German immigrants tended to travel as families and carried with them skills and capital that enabled them to enter middle-class trades. Germans migrated to the Old Northwest to farm in rural areas and practiced trades in growing communities such as St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Milwaukee, three cities that formed what came to be called the German Triangle.

尽管爱尔兰人大多定居在沿海城市,但大多数德国移民将美国港口和城市作为临时中转站,然后定居在农村。在内战前时期,有超过150万来自各个德国州的移民抵达美国。尽管一些德国南部人逃离了农业条件恶化和1848年革命失败的后果,但许多德国人只是为了寻求更稳定的经济机会。德国移民倾向于以家庭为单位旅行,并随身携带使他们能够进入中产阶级行业的技能和资本。德国人移民到旧西北部在农村地区耕作,并在圣路易斯、辛辛那提和密尔沃基等新兴社区从事贸易,这三个城市形成了所谓的德国三角区。

Catholic and Jewish Germans transformed regions of the republic. Although records are sparse, New York’s Jewish population rose from approximately five hundred in 1825 to forty thousand in 1860. Similar gains were seen in other American cities. Jewish immigrants hailing from southwestern Germany and parts of occupied Poland moved to the United States through chain migration and as family units. Unlike other Germans, Jewish immigrants rarely settled in rural areas. Once established, Jewish immigrants found work in retail, commerce, and artisanal occupations such as tailoring. They quickly found their footing and established themselves as an intrinsic part of the American market economy. Just as Irish immigrants shaped the urban landscape through the construction of churches and Catholic schools, Jewish immigrants erected synagogues and made their mark on American culture.

天主教和犹太德国人改变了共和国的地区。尽管记录很少,但纽约的犹太人口从1825年的约500人增加到1860年的4万人。其他美国城市也出现了类似的增长。来自德国西南部和被占领波兰部分地区的犹太移民通过链式移民和家庭单位移居美国。与其他德国人不同,犹太移民很少定居在农村地区。一旦站稳脚跟,犹太移民就会在零售、商业和裁缝等手工业中找到工作。他们很快就找到了自己的立足点,并确立了自己在美国市场经济中不可或缺的一部分。正如爱尔兰移民通过建造教堂和天主教学校塑造了城市景观一样,犹太移民也建造了犹太教堂,并在美国文化中留下了自己的印记。

The sudden influx of immigration triggered a backlash among many native-born Anglo-Protestant Americans. This nativist movement, especially fearful of the growing Catholic presence, sought to limit European immigration and prevent Catholics from establishing churches and other institutions. Popular in northern cities such as Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and other cities with large Catholic populations, nativism even spawned its own political party in the 1850s. The American Party, more commonly known as the Know-Nothing Party, found success in local and state elections throughout the North. The party even nominated candidates for president in 1852 and 1856. The rapid rise of the Know-Nothings, reflecting widespread anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiment, slowed European immigration. Immigration declined precipitously after 1855 as nativism, the Crimean War, and improving economic conditions in Europe discouraged potential migrants from traveling to the United States. Only after the American Civil War would immigration levels match and eventually surpass the levels seen in the 1840s and 1850s.

移民的突然涌入引发了许多本土盎格鲁-新教美国人的强烈反对。这场排外运动,尤其害怕日益增长的天主教徒存在,试图限制欧洲移民,并阻止天主教徒建立教堂和其他机构。排外主义在波士顿、芝加哥、费城和其他天主教人口众多的北方城市很受欢迎,甚至在1850年代催生了自己的政党。美国党,更广为人知的名称是“一无所知党”,在整个北方的州和地方选举中取得了成功。该党甚至在1852年和1856年提名了总统候选人。“一无所知党”的迅速崛起,反映了普遍的反天主教和反移民情绪,减缓了欧洲移民的步伐。1855年后,随着排外主义、克里米亚战争和欧洲经济状况的改善,移民急剧减少,这使得潜在的移民放弃了前往美国的想法。只有在美国内战之后,移民水平才会达到并最终超过1840年代和1850年代的水平。

In industrial northern cities, Irish immigrants swelled the ranks of the working class and quickly encountered the politics of industrial labor. Many workers formed trade unions during the early republic. Organizations such as Philadelphia’s Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers or the Carpenters’ Union of Boston operated within specific industries in major American cities. These unions worked to protect the economic power of their members by creating closed shops—workplaces wherein employers could only hire union members—and striking to improve working conditions. Political leaders denounced these organizations as unlawful combinations and conspiracies to promote the narrow self-interest of workers above the rights of property holders and the interests of the common good. Unions did not become legally acceptable until 1842 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of a union organized among Boston bootmakers, arguing that the workers were capable of acting “in such a manner as best to subserve their own interests.” Even after the case, unions remained in a precarious legal position.

在北方的工业城市,爱尔兰移民壮大了工人阶级的队伍,并很快遇到了工业劳工的政治问题。许多工人在早期共和国时期成立了工会。费城的熟练鞋匠联邦协会或波士顿的木匠工会等组织在美国主要城市的特定行业内运作。这些工会通过创建封闭式商店(雇主只能雇用工会成员的工作场所)和罢工以改善工作条件来保护其成员的经济实力。政治领导人谴责这些组织是非法的联合和阴谋,旨在将工人的狭隘私利置于财产权所有者的权利和共同利益之上。直到1842年,工会才在法律上被接受,当时马萨诸塞州最高法院裁决支持波士顿制鞋匠中组织的工会,认为工人有能力以“最有利于自身利益的方式行事”。即使在案件之后,工会仍然处于不稳定的法律地位。

In the 1840s, labor activists organized to limit working hours and protect children in factories. The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics and Other Workingmen (NEA) mobilized to establish a ten-hour workday across industries. They argued that the ten-hour day would improve the immediate conditions of laborers by allowing “time and opportunities for intellectual and moral improvement.” After a citywide strike in Boston in 1835, the Ten-Hour Movement quickly spread to other major cities such as Philadelphia. The campaign for leisure time was part of the male working-class effort to expose the hollowness of the paternalistic claims of employers and their rhetoric of moral superiority.

在1840年代,劳工活动家组织起来限制工作时间和保护工厂中的儿童。新英格兰农民、机械师和其他工人协会(NEA)动员起来在各行业建立十小时工作制。他们认为,十小时工作制将通过允许“智力发展和道德提升的时间和机会”来改善劳动者的直接条件。在1835年波士顿全市范围内的罢工之后,十小时运动迅速蔓延到费城等其他主要城市。争取休闲时间的运动是男性工人阶级努力揭露雇主的家长式主张及其道德优越性言辞的空洞性的一部分。

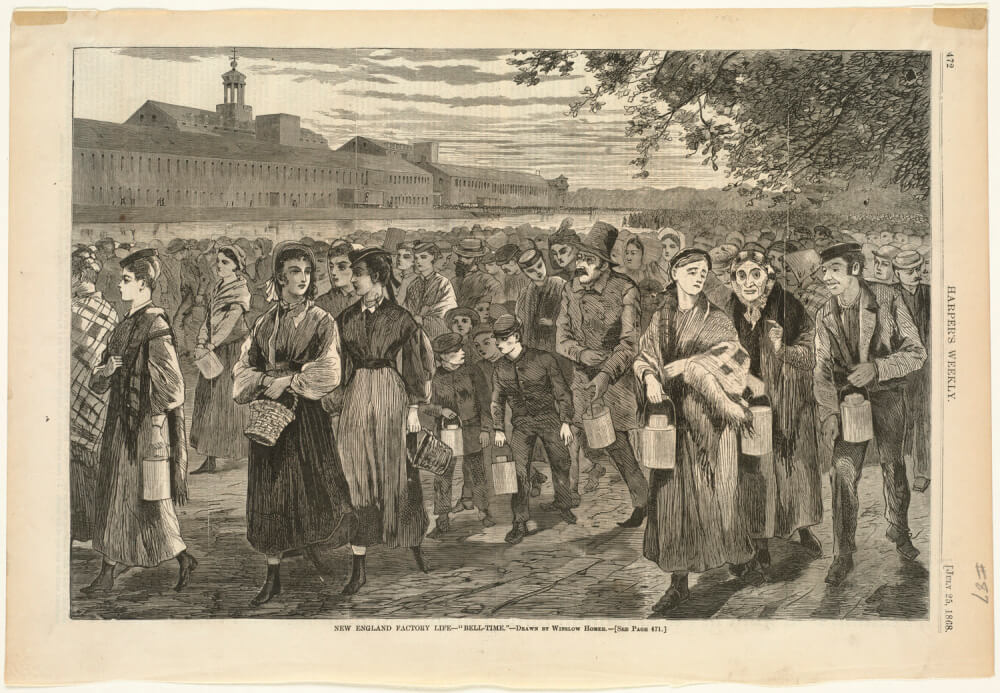

Women, a dominant labor source for factories since the early 1800s, launched some of the earliest strikes for better conditions. Textile operatives in Lowell, Massachusetts, “turned out” (walked off) their jobs in 1834 and 1836. During the Ten-Hour Movement of the 1840s, female operatives provided crucial support. Under the leadership of Sarah Bagley, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association organized petition drives that drew thousands of signatures from “mill girls.” Like male activists, Bagley and her associates used the desire for mental improvement as a central argument for reform. An 1847 editorial in the Voice of Industry, a labor newspaper published by Bagley, asked, “who, after thirteen hours of steady application to monotonous work, can sit down and apply her mind to deep and long continued thought?” Despite the widespread support for a ten-hour day, the movement achieved only partial success. President Martin Van Buren established a ten-hour-day policy for laborers on federal public works projects. New Hampshire passed a statewide law in 1847, and Pennsylvania followed a year later. Both states, however, allowed workers to voluntarily consent to work more than ten hours per day.

自1800年代初以来,妇女一直是工厂的主要劳动力来源,她们发起了最早的一些罢工以争取更好的条件。马萨诸塞州洛厄尔的纺织工人分别在1834年和1836年“辞职”(离职)了。在1840年代的十小时运动期间,女性工人提供了至关重要的支持。在莎拉·巴格利的领导下,洛厄尔女性劳工改革协会组织了请愿活动,吸引了数千名“工厂女孩”的签名。与男性活动家一样,巴格利和她的同事也将对精神进步的渴望作为改革的主要论据。巴格利出版的劳工报纸《工业之声》1847年的一篇社论问道,“谁在连续13个小时从事单调的工作后,还能坐下来,将她的思想应用于深刻而持久的思考?”尽管十小时工作制得到了广泛支持,但该运动只取得了部分成功。马丁·范布伦总统为联邦公共工程项目的劳工建立了十小时工作制政策。新罕布什尔州在1847年通过了一项全州法律,宾夕法尼亚州在一年后效仿。然而,这两个州都允许工人自愿同意每天工作超过十小时。

In 1842, child labor became a dominant issue in the American labor movement. The protection of child laborers gained more middle-class support than the protection of adult workers. A petition from parents in Fall River, a southern Massachusetts mill town that employed a high portion of child workers, asked the legislature for a law “prohibiting the employment of children in manufacturing establishments at an age and for a number of hours which must be permanently injurious to their health and inconsistent with the education which is essential to their welfare.” Massachusetts quickly passed a law prohibiting children under age twelve from working more than ten hours a day. By the midnineteenth century, every state in New England had followed Massachusetts’s lead. Between the 1840s and 1860s, these statutes slowly extended the age of protection of labor and the assurance of schooling. Throughout the region, public officials agreed that young children (between ages nine and twelve) should be prevented from working in dangerous occupations, and older children (between ages twelve and fifteen) should balance their labor with education and time for leisure.

1842年,童工成为美国劳工运动中的一个主要问题。对童工的保护比对成年工人的保护获得了更多中产阶级的支持。来自马萨诸塞州南部米尔镇秋河(雇用了大量童工)的父母的请愿书要求立法机关制定一项法律,“禁止在制造业机构中雇用儿童,其年龄和工作时长必须永久损害他们的健康,并且与他们的福利所必需的教育不一致。”马萨诸塞州迅速通过了一项法律,禁止12岁以下的儿童每天工作超过10个小时。到19世纪中期,新英格兰的每个州都效仿了马萨诸塞州的榜样。在1840年代至1860年代之间,这些法规慢慢扩大了劳工保护的年龄和教育的保障。在该地区的整个过程中,公职人员一致认为,应禁止年幼的儿童(9至12岁之间)从事危险的职业,而年龄较大的儿童(12至15岁之间)应在劳动与教育和休闲之间取得平衡。

Male workers sought to improve their income and working conditions to create a household that kept women and children protected within the domestic sphere. But labor gains were limited, and the movement remained moderate. Despite its challenge to industrial working conditions, labor activism in antebellum America remained largely wedded to the free labor ideal. The labor movement later supported the northern free soil movement, which challenged the spread of slavery in the 1840s, simultaneously promoting the superiority of the northern system of commerce over the southern institution of slavery while trying, much less successfully, to reform capitalism.

男性工人试图提高他们的收入和工作条件,以创建一个将妇女和儿童保护在家庭领域内的家庭。但是,劳动力的收益是有限的,而且该运动仍然保持适度。尽管它挑战了工业劳动条件,但内战前美国劳工活动在很大程度上仍然与自由劳动理想紧密相连。劳工运动后来支持了1840年代挑战奴隶制蔓延的北方自由土地运动,同时宣传北方商业体系优于南方奴隶制度,同时尝试(但不太成功)改革资本主义。

VII. Conclusion

七、结论

During the early nineteenth century, southern agriculture produced by enslaved labor fueled northern industry produced by wage workers and managed by the new middle class. New transportation, new machinery, and new organizations of labor integrated the previously isolated pockets of the colonial economy into a national industrial operation. Industrialization and the cash economy tied diverse regions together at the same time that ideology drove Americans apart. By celebrating the freedom of contract that distinguished the wage worker from the indentured servant of previous generations or the enslaved laborer in the southern cotton field, political leaders claimed the American Revolution’s legacy for the North. But the rise of industrial child labor, the demands of workers to unionize, the economic vulnerability of women, and the influx of non-Anglo immigrants left many Americans questioning the meaning of liberty after the market revolution.

在19世纪初,南方由被奴役的劳动力生产的农业为北方由工资工人生产和由新兴中产阶级管理的工业提供了动力。新的交通、新的机械和新的劳动组织将以前孤立的殖民经济区域整合为一个全国性的工业运营。工业化和现金经济将不同的区域联系在一起,与此同时,意识形态将美国人分开。通过庆祝合同自由,这种自由将工资工人与前几代的契约仆人或南方棉花田里的被奴役劳动者区分开来,政治领导人声称美国革命的遗产属于北方。但工业童工的兴起、工人要求组织工会的呼声、妇女的经济脆弱性和非盎格鲁移民的涌入使许多美国人质疑市场革命后自由的意义。