第十章 宗教与改革

原标题:Religion and Reform

Source / 原文:https://www.americanyawp.com/text/10-religion-and-reform/

I. Introduction

一、引言

The early nineteenth century was a period of immense change in the United States. Economic, political, demographic, and territorial transformations radically altered how Americans thought about themselves, their communities, and the rapidly expanding nation. It was a period of great optimism, with the possibilities of self-governance infusing everything from religion to politics. Yet it was also a period of great conflict, as the benefits of industrialization and democratization increasingly accrued along starkly uneven lines of gender, race, and class. Westward expansion distanced urban dwellers from frontier settlers more than ever before, even as the technological innovations of industrialization—like the telegraph and railroads—offered exciting new ways to maintain communication. The spread of democracy opened the franchise to nearly all white men, but urbanization and a dramatic influx of European migration increased social tensions and class divides.

19世纪早期是美国经历巨大变革的时期。经济、政治、人口和领土的转型深刻改变了美国人对自我、社区以及迅速扩张的国家的看法。这是一个充满乐观的时代,自我治理的可能性渗透到从宗教到政治的方方面面。然而,这也是一个充满冲突的时期,因为工业化和民主化的益处日益集中地分配在性别、种族和阶级的鲜明分界线上。西部扩张使城市居民与边境定居者之间的距离比以往任何时候都更远,但工业化的技术创新——如电报和铁路——又提供了令人兴奋的新方式来保持联系。民主的传播让几乎所有白人男性都获得了选举权,但城市化和大量欧洲移民的涌入加剧了社会紧张和阶级分化。

Americans looked on these changes with a mixture of enthusiasm and suspicion, wondering how the moral fabric of the new nation would hold up to emerging social challenges. Increasingly, many turned to two powerful tools to help understand and manage the various transformations: spiritual revivalism and social reform. Reacting to the rationalism of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, the religious revivals of the Second Great Awakening reignited Protestant spirituality during the early nineteenth century. The revivals incorporated worshippers into an expansive religious community that crisscrossed all regions of the United States and armed them with a potent evangelical mission. Many emerged from these religious revivals with a conviction that human society could be changed to look more heavenly. They joined their spiritual networks to rapidly developing social reform networks that sought to alleviate social ills and eradicate moral vice. Tackling numerous issues, including alcoholism, slavery, and the inequality of women, reformers worked tirelessly to remake the world around them. While not all these initiatives were successful, the zeal of reform and the spiritual rejuvenation that inspired it were key facets of antebellum life and society.

美国人以一种既充满热情又夹杂怀疑的态度看待这些变革,担心这个新兴国家的道德基石是否能经受住不断出现的社会挑战。越来越多的人转向两个强有力的工具来理解和应对这些转型:宗教复兴和社会改革。作为对18世纪启蒙理性主义的反应,19世纪初的“第二次大觉醒”宗教复兴重新点燃了新教的灵性。这些复兴运动将信徒融入一个横跨美国各个地区的广泛宗教共同体,并赋予他们强大的福音传播使命。许多人从这些宗教复兴中获得了信念,认为人类社会可以被改变得更加接近天堂的理想模样。这些人将自己的宗教网络与迅速发展的社会改革网络结合在一起,致力于缓解社会弊病和根除道德恶习。他们关注的问题包括酗酒、奴隶制以及女性的不平等。改革者们不懈努力,希望重塑身边的世界。尽管并非所有这些举措都取得了成功,但改革的热情以及激励其背后的精神复兴,成为前南北战争时期生活与社会的关键特征。

II. Revival and Religious Change

二、宗教复兴与宗教变革

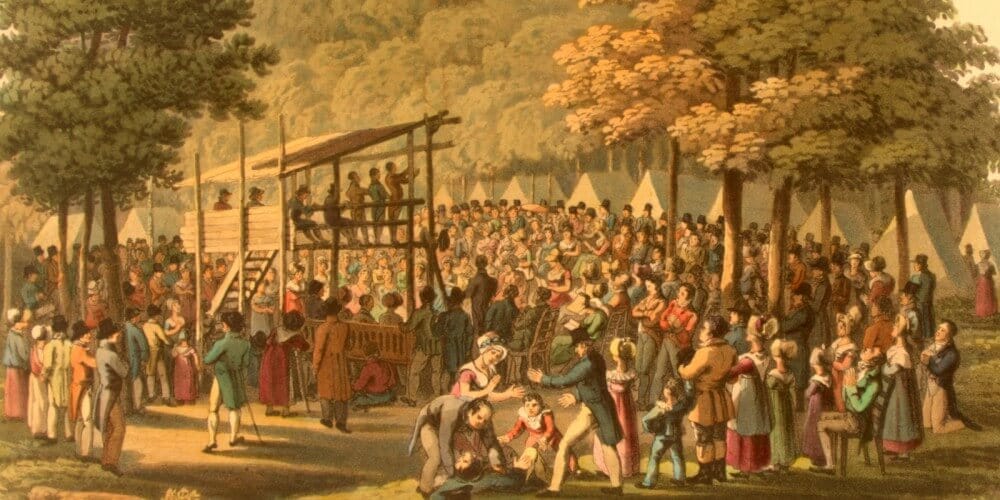

In the early nineteenth century, a succession of religious revivals collectively known as the Second Great Awakening remade the nation’s religious landscape. Revivalist preachers traveled on horseback, sharing the message of spiritual and moral renewal to as many as possible. Residents of urban centers, rural farmlands, and frontier territories alike flocked to religious revivals and camp meetings, where intense physical and emotional enthusiasm accompanied evangelical conversion.

19世纪初,一系列统称为“第二次大觉醒”的宗教复兴运动重塑了美国的宗教版图。复兴派布道者骑马穿行各地,尽可能多地传递灵性与道德更新的讯息。无论是城市居民、乡村农民,还是边疆领地的定居者,都纷纷涌向宗教复兴集会和露天布道会。这些聚会伴随着强烈的身体和情感热情,激发了人们的福音皈依。

The Second Great Awakening emerged in response to powerful intellectual and social currents. Camp meetings captured the democratizing spirit of the American Revolution, but revivals also provided a unifying moral order and new sense of spiritual community for Americans struggling with the great changes of the day. The market revolution, western expansion, and European immigration all challenged traditional bonds of authority, and evangelicalism promised equal measures of excitement and order. Revivals spread like wildfire throughout the United States, swelling church membership, spawning new Christian denominations, and inspiring social reform.

“第二次大觉醒”的兴起,是对强大的知识和社会潮流的回应。露天布道会体现了美国革命中的民主精神,但复兴运动也为那些应对当时重大变革的美国人提供了一种统一的道德秩序和新的精神共同体。市场革命、西部扩张和欧洲移民的涌入挑战了传统权威的纽带,而福音主义则在提供兴奋感与秩序感之间找到了平衡。复兴运动如野火般席卷美国,教会成员激增,新教派不断涌现,并激发了广泛的社会改革。

One of the earliest and largest revivals of the Second Great Awakening occurred in Cane Ridge, Kentucky, over a one-week period in August 1801. The Cane Ridge Revival drew thousands of people, and possibly as many as one of every ten residents of Kentucky. Though large crowds had previously gathered annually in rural areas each late summer or fall to receive communion, this assembly was very different. Methodist, Baptist, and Presbyterian preachers all delivered passionate sermons, exhorting the crowds to strive for their own salvation. They preached from inside buildings, evangelized outdoors under the open sky, and even used tree stumps as makeshift pulpits, all to reach their enthusiastic audiences in any way possible. Women, too, exhorted, in a striking break with common practice. Attendees, moved by the preachers’ fervor, responded by crying, jumping, speaking in tongues, or even fainting.

“第二次大觉醒”中最早也是规模最大的复兴之一,发生在1801年8月于肯塔基州的凯恩岭。这个为期一周的凯恩岭复兴聚会吸引了成千上万的人,参与者可能占到当时肯塔基州总人口的十分之一。尽管此前每年夏末或秋季,乡村地区都会举行大规模的圣餐聚会,但此次集会完全不同。卫理公会、浸信会和长老会的布道者纷纷发表充满激情的布道,激励人群追求个人的救赎。他们不仅在建筑物内宣讲,还在露天环境中传教,甚至利用树桩作为临时讲台,竭尽所能接触到充满热情的听众。令人惊讶的是,女性也参与布道,打破了传统惯例。听众深受布道者热情的感染,回应的方式五花八门,包括哭泣、跳跃、说方言,甚至昏厥。

Events like the Cane Ridge Revival did spark significant changes in Americans’ religious affiliations. Many revivalists abandoned the comparatively formal style of worship observed in the well-established Congregationalist and Episcopalian churches and instead embraced more impassioned forms of worship that included the spontaneous jumping, shouting, and gesturing found in new and alternative denominations. The ranks of Christian denominations such as the Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians swelled precipitously alongside new denominations such as the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. The evangelical fire reached such heights, in fact, that one swath of western and central New York state came to be known as the Burned-Over District. Charles Grandison Finney, the influential revivalist preacher who first coined the term, explained that the residents of this area had experienced so many revivals by different religious groups that there were no more souls to awaken to the fire of spiritual conversion.

凯恩岭复兴等事件确实引发了美国宗教归属的显著变化。许多复兴派信徒放弃了会众派和圣公会等传统教会较为正式的礼拜形式,转而接受更加热情洋溢的敬拜方式,这些形式包括即兴跳跃、呼喊以及肢体动作等表现。此类敬拜方式使卫理公会、浸信会和长老会等基督教宗派的成员人数急剧增加,同时催生了如基督复临安息日会这样的新宗派。这股福音主义的狂热甚至达到如此高的程度,以至于纽约州西部和中部的某些地区被称为“燃烧地带”。著名复兴派布道者查尔斯·格兰迪森·芬尼首次使用了这一术语,他解释说,这片地区的居民经历了太多宗教复兴运动,以至于已经“没有灵魂可以再被唤醒投向信仰的火焰”。

Removing the government support of churches created what historians call the American spiritual marketplace. Methodism achieved the most remarkable success, enjoying the most significant denominational increase in American history. By 1850, Methodism was by far the most popular American denomination. The Methodist denomination grew from fewer than one thousand members at the end of the eighteenth century to constitute 34 percent of all American church membership by the midnineteenth century. After its leaders broke with the Church of England to form a new American denomination in 1784, the Methodist Episcopal Church (MEC) achieved its growth through innovation. Methodists used itinerant preachers, known as circuit riders. These men (and the occasional woman) won converts by pushing west with the expanding United States over the Alleghenies and into the Ohio River Valley, bringing religion to new settlers hungry to have their spiritual needs attended. Circuit riding took preachers into homes, meetinghouses, and churches, all mapped out at regular intervals that collectively took about two weeks to complete.

随着政府逐步取消对教会的资助,美国形成了历史学家所称的“精神市场”。在这一背景下,卫理公会取得了尤为显著的成功,成为美国历史上增长最为迅猛的宗派。到1850年,卫理公会已成为美国最受欢迎的宗教派别。该宗派的成员人数从18世纪末的不足千人迅速增长,到19世纪中叶已占全美教会成员总数的34%。1784年,卫理公会领导人与英国圣公会决裂,成立了新的美国宗派——卫理公会圣公会(Methodist Episcopal Church,MEC)。这一宗派的增长得益于创新性的布道方式,例如巡回布道者。这些布道者(偶尔也有女性)伴随着美国向西部的扩张,越过阿巴拉契亚山脉,深入俄亥俄河谷,为渴望灵性滋养的移民提供宗教服务。他们的布道活动涵盖家庭、集会所和教堂,按照约两周完成一轮的固定路线进行。

Revolutionary ideals also informed a substantial theological critique of orthodox Calvinism that had far-reaching consequences for religious individuals and for society as a whole. Calvinists believed that all of humankind was marred by sin, and God predestined only some for salvation. These attitudes began to seem too pessimistic for many American Christians. Worshippers increasingly began to take responsibility for their own spiritual fates by embracing theologies that emphasized human action in effecting salvation, and revivalist preachers were quick to recognize the importance of these cultural shifts. Radical revivalist preachers, such as Charles Grandison Finney, put theological issues aside and evangelized by appealing to worshippers’ hearts and emotions. Even more conservative spiritual leaders, such as Lyman Beecher of the Congregational Church, appealed to younger generations of Americans by adopting a less orthodox approach to Calvinist doctrine. Though these men did not see eye to eye, they both contributed to the emerging consensus that all souls are equal in salvation and that all people can be saved by surrendering to God. This idea of spiritual egalitarianism was one of the most important transformations to emerge out of the Second Great Awakening.

革命理想还促成了对正统加尔文主义的深刻神学批判,并对信徒以及整个社会产生了广泛的影响。加尔文主义强调人类因原罪而堕落,且上帝仅预定少数人得救。然而,许多美国基督徒开始认为这种观点过于悲观。越来越多的人开始主动掌控自己的灵性命运,接受那些强调个人行为能够影响得救结果的神学观点。复兴派布道者敏锐地察觉到这些文化转变的重要性,迅速调整布道策略。激进的复兴派布道者如查尔斯·格兰迪森·芬尼,将神学争议置于一旁,更多地通过唤起信徒的情感和心灵来传教。即便是较为保守的宗教领袖,如会众派的莱曼·比彻,也通过适度调整加尔文主义教义来吸引年轻一代的美国人。尽管这些布道者在具体观点上存在分歧,但他们共同促成了一种新兴共识的形成:所有灵魂在得救面前是平等的,每个人都可以通过向上帝臣服而获得救赎。这种“灵性平等”的理念成为第二次大觉醒中最重要的变革之一。

Spiritual egalitarianism dovetailed neatly with an increasingly democratic United States. In the process of winning independence from Britain, the revolution weakened the power of long-standing social hierarchies and the codes of conduct that went along with them. The democratizing ethos opened the door for a more egalitarian approach to spiritual leadership. Whereas preachers of long-standing denominations like the Congregationalists were required to have a divinity degree and at least some theological training in order to become spiritual leaders, many alternative denominations only required a conversion experience and a supernatural “call to preach.” This meant, for example, that a twenty-year-old man could go from working in a mill to being a full-time circuit-riding preacher for the Methodists practically overnight. Indeed, their emphasis on spiritual egalitarianism over formal training enabled Methodists to outpace spiritual competition during this period. Methodists attracted more new preachers to send into the field, and the lack of formal training meant that individual preachers could be paid significantly less than a Congregationalist preacher with a divinity degree.

灵性平等主义与日益民主化的美国社会紧密契合。在赢得独立的过程中,美国革命削弱了长期存在的社会等级制度及其附带的行为规范。这种民主化精神为更加平等的宗教领导方式铺平了道路。传统宗派(如会众派)的布道者通常需要获得神学学位并接受一定的神学训练,才能成为灵性领袖,而许多新兴宗派仅要求经历过信仰转变并接受“超自然的布道召唤”即可。这意味着,一名二十岁的年轻人可以从纺织厂工人迅速转变为卫理公会的全职巡回布道者,几乎一夜之间完成角色转变。事实上,卫理公会对灵性平等的强调使其在这一时期超越了其他宗派的竞争。通过吸引更多的新布道者加入,卫理公会能够向更广泛的地区派遣布道者。而由于无需正式的神学训练,个别布道者的薪酬也大幅低于拥有神学学位的会众派牧师。这种灵活的模式不仅降低了宗派的运营成本,还显著推动了其成员和影响力的快速增长。

In addition to the divisions between evangelical and nonevangelical denominations wrought by the Second Great Awakening, the revivals and subsequent evangelical growth also revealed strains within the Methodist and Baptist churches. Each witnessed several schisms during the 1820s and 1830s as reformers advocated for a return to the practices and policies of an earlier generation. Many others left mainstream Protestantism altogether, opting instead to form their own churches. Some, like Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone, proposed a return to (or “restoration” of) New Testament Christianity, stripped of centuries of additional teachings and practices. Other restorationists built on the foundation laid by the evangelical churches by using their methods and means to both critique the Protestant mainstream and move beyond the accepted boundaries of contemporary Christian orthodoxy. Self-declared prophets claimed that God had called them to establish new churches and introduce new (or, in their understanding, restore lost) teachings, forms of worship, and even scripture.

除了第二次大觉醒引发的福音派和非福音派宗派之间的分裂外,这场复兴及其后续的福音派发展也暴露了卫理公会和浸信会内部的紧张关系。在1820年代和1830年代,这两个宗派都经历了多次分裂,因为一些改革者主张回归早期一代的宗教实践和政策。此外,还有许多人完全脱离了主流新教,转而建立自己的教会。例如,亚历山大·坎贝尔和巴顿·斯通提议回归(或“复原”)新约时代的基督教,摒弃了数个世纪以来附加的教义和实践。其他复原主义者则以福音派教会奠定的基础为起点,利用其方法和手段批判新教主流,同时超越当时基督教正统所接受的界限。这些自称先知的人宣称,他们受到了上帝的召唤,要建立新的教会,并引入新的(或者按照他们的理解,恢复失落的)教义、礼拜形式,甚至是经文。这些努力在进一步扩大宗派多样性的同时,也挑战了传统基督教的结构和理念。

Mormon founder Joseph Smith, for example, claimed that God the Father and Jesus Christ appeared to him in a vision in a grove of trees near his boyhood home in upstate New York and commanded him to “join none of [the existing churches], for they are all wrong.” Subsequent visitations from angelic beings revealed to Smith the location of a buried record, purportedly containing the writings and histories of an ancient Christian civilization on the American continent. Smith published the Book of Mormon in early 1830 and organized the Church of Christ (later renamed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints) a short time later. Borrowing from the Methodists a faith in the abilities of itinerant preachers without formal training, Smith dispatched early converts as missionaries to take the message of the Book of Mormon throughout the United States, across the ocean to England and Ireland, and eventually even farther abroad. He attracted a sizable number of followers on both sides of the Atlantic and commanded them to gather to a center place, where they collectively anticipated the imminent second coming of Christ. Continued growth and near-constant opposition from both Protestant ministers and neighbors suspicious of their potential political power forced the Mormons to move several times, first from New York to Ohio, then to Missouri, and finally to Illinois, where they established a thriving community on the banks of the Mississippi River. In Nauvoo, as they called their city, Smith moved even further beyond the bounds of the Christian orthodoxy by continuing to pronounce additional revelations and introducing sacred rites to be performed only in front of church members in Mormon temples. Most controversially, Smith and a select group of his most loyal followers began taking additional wives (Smith himself married at least thirty women). Although Mormon polygamy was not publicly acknowledged and openly practiced until 1852 (when the Mormons had moved yet again, this time to the protective confines of the intermountain west on the shores of the Great Salt Lake), rumors of Smith’s involvement circulated almost immediately after its quiet introduction and played a part in the motivations of the mob that eventually murdered the Mormon prophet in the summer of 1844.

摩门教创始人约瑟夫·斯密声称,他在纽约州北部的家附近树林中经历了一场异象,见到了天父和耶稣基督。这次显现中,他被告知“不要加入任何现有的教会,因为它们都偏离了正道。”之后,他接连获得天使的启示,得知一份埋藏的记录的具体位置。这份记录据称记载了一个古代基督教文明在美洲大陆的历史和教义。1830年初,斯密出版了《摩门经》,随后创立了基督教会(后来更名为耶稣基督后期圣徒教会)。受到卫理公会对无正规培训的巡回传教士的信任启发,斯密派遣早期信徒作为传教士,传播《摩门经》的信息。他们的足迹遍布美国,并远渡重洋,将教义带到英格兰和爱尔兰,最终进一步扩展到更遥远的地区。他在大西洋两岸吸引了大量追随者,并指示他们向一个“中心之地”聚集,共同期待基督即将到来的第二次降临。然而,随着摩门教徒人数的不断增长,他们面临的反对也持续升级。这些反对来自新教牧师以及对摩门教徒潜在政治影响感到不安的邻居。摩门教徒多次迁移,从纽约到俄亥俄,再到密苏里,最后在伊利诺伊州密西西比河畔建立了一个名为纳府(Nauvoo)的繁荣社区。在纳府,斯密继续超越传统基督教的教义。他不断宣告新的启示,并创立了一些只能在摩门教圣殿中面向教会成员执行的神圣仪式。最具争议的是,斯密和一部分忠诚追随者秘密实行一夫多妻制(斯密本人至少娶了30位妻子)。虽然这一制度直到1852年摩门教徒迁至大盐湖地区后才被公开,但其早期的传闻迅速传播开来,并成为1844年夏天斯密遭暴民谋杀的原因之一。

Mormons were not the only religious community in antebellum America to challenge the domestic norms of the era through radical sexual experiments: Shakers strictly enforced celibacy in their several communes scattered throughout New England and the upper Midwest, while John Humphrey Noyes introduced free love (or “complex marriage”) to his Oneida community in upstate New York. Others challenged existing cultural customs in less radical ways. For individual worshippers, spiritual egalitarianism in revivals and camp meetings could break down traditional social conventions. For example, revivals generally admitted both men and women. Furthermore, in an era when many American Protestants discouraged or outright forbade women from speaking in church meetings, some preachers provided women with new opportunities to openly express themselves and participate in spiritual communities. This was particularly true in the Methodist and Baptist traditions, though by the midnineteenth century most of these opportunities would be curtailed as these denominations attempted to move away from radical revivalism and toward the status of respectable denominations. Some preachers also promoted racial integration in religious gatherings, expressing equal concern for white and Black people’s spiritual salvation and encouraging both enslavers and the enslaved to attend the same meetings. Historians have even suggested that the extreme physical and vocal manifestations of conversion seen at impassioned revivals and camp meetings offered the ranks of worshippers a way to enact a sort of social leveling by flouting the codes of self-restraint prescribed by upper-class elites. Although the revivals did not always live up to such progressive ideals in practice, particularly in the more conservative regions of the slaveholding South, the concept of spiritual egalitarianism nonetheless changed how Protestant Americans thought about themselves, their God, and one another.

摩门教并不是前南北战争时期美国唯一一个通过激进的性观念实验挑战当时社会规范的宗教团体。谢克派在新英格兰和中西部上游地区的多个公社中严格推行独身主义,而约翰·汉弗莱·诺伊斯(John Humphrey Noyes)则在纽约州上部的奥奈达社区引入了自由恋爱(或称“复杂婚姻”)。除此之外,还有一些群体通过不那么激进的方式挑战既有的文化习俗。对于个人信徒而言,复兴聚会和营地聚会中所体现的信仰平等观(spiritual egalitarianism)能够打破传统的社会规范。例如,复兴聚会通常接纳男性和女性共同参与。此外,在许多美国新教教派阻止甚至明令禁止女性在教会会议上发言的时代,一些布道者为女性提供了公开表达自我和参与灵性社群的新机会。这种情况在卫理公会和浸信会传统中尤为常见,尽管到19世纪中期,随着这些教派试图从激进的复兴主义转向更为体面的宗教团体,这些机会大多被削减。一些布道者还在宗教聚会中倡导种族融合,平等关注白人和黑人灵魂的救赎,鼓励奴隶主与被奴役者共同参与同一聚会。历史学家甚至认为,在充满激情的复兴聚会和营地聚会中所见的强烈身体和声音表达,提供了一种打破上层阶级规定的自我克制规范的社会平等方式。尽管复兴运动在实践中未必始终践行这些进步理念,尤其是在保守的蓄奴南方地区,但信仰平等观的理念无疑改变了新教美国人对自身、对上帝以及对彼此的看法。

As the borders of the United States expanded during the nineteenth century and as new demographic changes altered urban landscapes, revivalism also offered worshippers a source of social and religious structure to help cope with change. Revival meetings held by itinerant preachers offered community and collective spiritual purpose to migrant families and communities isolated from established social and religious institutions. In urban centers, where industrialization and European famines brought growing numbers of domestic and foreign migrants, evangelical preachers provided moral order and spiritual solace to an increasingly anonymous population. Additionally, and quite significantly, the Second Great Awakening armed evangelical Christians with a moral purpose to address and eradicate the many social problems they saw as arising from these dramatic demographic shifts.

随着19世纪美国边界的扩张以及新的人口变化改变了城市景观,复兴主义也为信徒提供了一种社会和宗教结构,帮助他们应对变革。由巡回布道者主持的复兴聚会为迁徙家庭以及那些与现有社会和宗教机构隔绝的社区提供了归属感和共同的精神目标。在工业化和欧洲饥荒导致国内外移民大量涌入的城市中心,福音派布道者为日益匿名化的人群提供了道德秩序和精神慰藉。此外,更为重要的是,第二次大觉醒为福音派基督徒赋予了一种道德使命,促使他们致力于解决和消除这些剧烈人口变化所带来的众多社会问题。

Not all American Christians, though, were taken with the revivals. The early nineteenth century also saw the rise of Unitarianism as a group of ministers and their followers came to reject key aspects of “orthodox” Protestant belief including the divinity of Christ. Christians in New England were particularly involved in the debates surrounding Unitarianism as Harvard University became a hotly contested center of cultural authority between Unitarians and Trinitarians. Unitarianism had important effects on the world of reform when a group of Unitarian ministers founded the Transcendental Club in 1836. The club met for four years and included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Frederic Henry Hedge, George Ripley, Orestes Brownson, James Freeman Clarke, and Theodore Parker. While initially limited to ministers or former ministers—except for the eccentric Alcott—the club quickly expanded to include numerous literary intellectuals. Among these were the author Henry David Thoreau, the protofeminist and literary critic Margaret Fuller, and the educational reformer Elizabeth Peabody.

然而,并非所有美国基督徒都接受复兴主义。19世纪初,基督教界出现了一个名为“一神论”(Unitarianism)的兴起派别。一些牧师及其追随者开始拒绝“正统”新教信仰的关键要素,包括基督的神性。新英格兰地区的基督徒尤其热衷于围绕一神论展开辩论,哈佛大学成为了一神论者与三位一体论者之间激烈争夺文化权威的中心。一神论对改革领域产生了重要影响。1836年,一群一神论牧师创立了超验主义俱乐部(Transcendental Club)。该俱乐部持续了四年,成员包括拉尔夫·沃尔多·爱默生(Ralph Waldo Emerson)、布朗森·奥尔科特(Bronson Alcott)、弗雷德里克·亨利·赫奇(Frederic Henry Hedge)、乔治·里普利(George Ripley)、奥雷斯特斯·布朗森(Orestes Brownson)、詹姆斯·弗里曼·克拉克(James Freeman Clarke)和西奥多·帕克(Theodore Parker)。起初,俱乐部仅限于牧师或前牧师参加(古怪的奥尔科特除外),但不久后便扩展到包括众多文学知识分子。其中著名人物包括作家亨利·大卫·梭罗(Henry David Thoreau)、早期女权主义者兼文学评论家玛格丽特·富勒(Margaret Fuller)以及教育改革家伊丽莎白·皮博迪(Elizabeth Peabody)。

Transcendentalism had no established creed, but this was intentional. What united the Transcendentalists was their belief in a higher spiritual principle within each person that could be trusted to discover truth, guide moral action, and inspire art. They often referred to this principle as Soul, Spirit, Mind, or Reason. Deeply influenced by British Romanticism and German idealism’s celebration of individual artistic inspiration, personal spiritual experience, and aspects of human existence not easily explained by reason or logic, the Transcendentalists established an enduring legacy precisely because they developed distinctly American ideas that emphasized individualism, optimism, oneness with nature, and a modern orientation toward the future rather than the past. These themes resonated in an American nineteenth century where political democracy and readily available land distinguished the United States from Europe.

超验主义并没有固定的信条,这一特点是刻意为之。超验主义者的共同信念是:每个人内在都蕴藏着一种更高的精神原则,这种原则能够被信任,用来发现真理、引导道德行为并激发艺术创作。他们通常称这一原则为“灵魂”、“精神”、“心灵”或“理性”。超验主义深受英国浪漫主义和德国唯心主义的影响,特别是其中对个体艺术灵感、个人精神体验以及理性或逻辑难以解释的人类存在方面的赞美。然而,超验主义者的持久影响力正是源于他们发展出独具美国特色的理念,强调个体主义、乐观主义、人类与自然的统一,以及面向未来而非拘泥于过去的现代视角。这些主题在19世纪的美国产生了共鸣,当时的政治民主和广阔的土地资源使美国与欧洲形成了鲜明对比。

Ralph Waldo Emerson espoused a religious worldview wherein God, “the eternal ONE,” manifested through the special harmony between the individual soul and nature. In “The American Scholar” (1837) and “Self-Reliance” (1841), Emerson emphasized the utter reliability and sufficiency of the individual soul and exhorted his audience to overcome “our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands.” Emerson believed that the time had come for Americans to declare their intellectual independence from Europe. Henry David Thoreau espoused a similar enthusiasm for simple living, communion with nature, and self-sufficiency. Thoreau’s sense of rugged individualism, perhaps the strongest among even the Transcendentalists, also yielded “Resistance to Civil Government” (1849). Several of the Transcendentalists also participated in communal living experiments. For example, in the mid-1840s, George Ripley and other members of the utopian Brook Farm community began to espouse Fourierism, a vision of society based on cooperative principles, as an alternative to capitalist conditions.

拉尔夫·沃尔多·爱默生提倡一种宗教世界观,认为上帝,即“永恒的唯一”,通过个体灵魂与自然之间的特殊和谐显现。在《美国学者》(1837年)和《自立》(1841年)中,爱默生强调个体灵魂的绝对可靠性和充足性,并告诫听众克服“对他国学问的长期学徒状态”。他坚信,美国人应该宣布从欧洲思想传统中获得知识上的独立。亨利·戴维·梭罗也表达了对简单生活、与自然交流以及自给自足的热情。梭罗展现了或许在超验主义者中最强烈的个体主义精神,这种精神还体现在他1849年的著作《论公民的不服从》中。此外,许多超验主义者还参与了集体生活的实验。例如,在19世纪40年代中期,乔治·里普利和乌托邦布鲁克农场社区的其他成员开始推崇傅立叶主义,这是一种基于合作原则的社会愿景,作为资本主义条件的替代方案。

Many of these different types of responses to the religious turmoil of the time had a similar endpoint in the embrace of voluntary associations and social reform work. During the antebellum period, many American Christians responded to the moral anxiety of industrialization and urbanization by organizing to address specific social needs. Social problems such as intemperance, vice, and crime assumed a new and distressing scale that older solutions, such as almshouses, were not equipped to handle. Moralists grew concerned about the growing mass of urban residents who did not attend church, and who, thanks to poverty or illiteracy, did not even have access to scripture. Voluntary benevolent societies exploded in number to tackle these issues. Led by ministers and dominated by middle-class women, voluntary societies printed and distributed Protestant tracts, taught Sunday school, distributed outdoor relief, and evangelized in both frontier towns and urban slums. These associations and their evangelical members also lent moral backing and workers to large-scale social reform projects, including the temperance movement designed to curb Americans’ consumption of alcohol, the abolitionist campaign to eradicate slavery in the United States, and women’s rights agitation to improve women’s political and economic rights. As such wide-ranging reform projects combined with missionary zeal, evangelical Christians formed a “benevolent empire” that swiftly became a cornerstone of the antebellum period.

面对工业化和城市化带来的宗教动荡,许多不同类型的回应最终都趋向于拥抱志愿组织和社会改革工作。在战前时期,许多美国基督徒为了应对因工业化和城市化引发的道德焦虑,组织起来解决具体的社会需求。酗酒、不道德行为和犯罪等社会问题呈现出新的、更令人不安的规模,而像救济院这样的传统手段已无法应对。道德主义者开始担忧城市中越来越多的人不参加教会活动,其中一些人由于贫困或文盲,甚至无法接触到《圣经》。志愿慈善协会的数量激增,专门处理这些问题。在牧师的领导下,并由中产阶级女性主导,这些志愿组织印刷和分发新教小册子,教授主日学校课程,提供户外救济,并在边疆城镇和城市贫民区进行福音传教。这些组织及其福音派成员还为大规模社会改革项目提供了道德支持和劳动力,这些项目包括旨在减少美国人酒精消费的禁酒运动、旨在废除美国奴隶制的废奴运动,以及旨在改善妇女政治和经济权利的妇女权利运动。随着这些广泛的改革项目与传教热情结合,福音派基督徒形成了一个“慈善帝国”,迅速成为战前时期的基石之一。

III. Atlantic Origins of Reform

三、大西洋视角下的改革起源

The reform movements that emerged in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century were not American inventions. Instead, these movements were rooted in a transatlantic world where both sides of the ocean faced similar problems and together collaborated to find similar solutions. Many of the same factors that spurred American reformers to action—such as urbanization, industrialization, and class struggle—equally affected Europe. Reformers on both sides of the Atlantic visited and corresponded with one another. Exchanging ideas and building networks proved crucial to shared causes like abolition and women’s rights.

19世纪上半叶在美国兴起的改革运动并非完全是美国本土的创造。这些运动的根源在于一个跨大西洋的世界,在这一世界中,大西洋两岸面临着类似的问题,并共同协作寻找类似的解决方案。推动美国改革者采取行动的许多因素,例如城市化、工业化和阶级斗争,同样也影响着欧洲。大西洋两岸的改革者相互访问并保持通信,交流思想并建立网络对废奴运动和妇女权利等共同事业至关重要。

Improvements in transportation, including the introduction of the steamboat, canals, and railroads, connected people not just across the United States, but also with other like-minded reformers in Europe. (Ironically, the same technologies also helped ensure that even after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, the British remained heavily invested in slavery, both directly and indirectly.) Equally important, the reduction of publication costs created by new printing technologies in the 1830s allowed reformers to reach new audiences across the world. Almost immediately after its publication in the United States, for instance, Frederick Douglass’s autobiography was republished in Europe and translated into French and Dutch. This abolitionist who escaped enslavement earned supporters across the Atlantic.

交通运输的进步,包括蒸汽船、运河和铁路的引入,不仅连接了美国各地的人们,也将志同道合的欧洲改革者联系在了一起。(具有讽刺意味的是,这些同样的技术也确保了即使在英国废除奴隶制之后,英国仍通过直接或间接的方式深深卷入奴隶制。)同样重要的是,19世纪30年代新印刷技术带来的出版成本下降,使得改革者能够接触到全球范围内的新受众。例如,弗雷德里克·道格拉斯的自传在美国出版后几乎立刻在欧洲再版,并被翻译成法语和荷兰语。这位从奴役中逃脱的废奴主义者在大西洋两岸赢得了众多支持者。

Such exchanges began as part of the larger processes of colonialism and empire building. Missionary organizations from the colonial era had created many of these transatlantic links. The Atlantic travel of major figures during the First Great Awakening such as George Whitefield had built enduring networks. These networks changed as a result of the American Revolution but still revealed spiritual and personal connections between religious individuals and organizations in the United States and Great Britain. These connections can be seen in multiple areas. Mission work continued to be a joint effort, with American and European missionary societies in close correspondence throughout the early nineteenth century, as they coordinated domestic and foreign evangelistic missions. The transportation and print revolutions meant that news of British missionary efforts in India and Tahiti could be quickly printed in American religious periodicals, galvanizing American efforts to evangelize Native Americans, frontier settlers, immigrant groups, and even people overseas.

此类交流最初是殖民主义和帝国建构过程中更大趋势的一部分。殖民时期的传教组织建立了许多这样的跨大西洋联系。在第一次大觉醒中,乔治·怀特菲尔德等重要人物的跨大西洋旅行构建了持久的网络。这些网络在美国革命后发生了变化,但仍然展现出美国和英国宗教个人及组织之间的精神和个人联系。这种联系体现在多个领域。传教工作依旧是双方的共同努力,美国和欧洲的传教团体在19世纪初期保持着密切的通信,协调国内和海外的布道任务。交通与印刷革命使得英国在印度和塔希提的传教活动能够迅速通过美国的宗教期刊传播,这激发了美国对原住民、边境定居者、移民群体乃至海外人群的布道热情。

In addition to missions, antislavery work had a decidedly transatlantic cast from its very beginnings. American Quakers began to question slavery as early as the late seventeenth century and worked with British reformers in the successful campaign that ended the slave trade. Before, during, and after the Revolution, many Americans continued to admire European thinkers. Influence extended both east and west. By foregrounding questions about rights, the American Revolution helped inspire British abolitionists, who in turn offered support to their American counterparts. American antislavery activists developed close relationships with abolitionists on the other side of the Atlantic, such as Thomas Clarkson, Daniel O’Connell, and Joseph Sturge. Prominent American abolitionists such as Theodore Dwight Weld, Lucretia Mott, and William Lloyd Garrison were converted to the antislavery idea of immediatism—that is, the demand for emancipation without delay—by British abolitionists Elizabeth Heyrick and Charles Stuart. Although Anglo-American antislavery networks reached back to the late eighteenth century, they dramatically grew in support and strength over the antebellum period, as evidenced by the General Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840. This antislavery delegation consisted of more than five hundred abolitionists, mostly coming from France, England, and the United States. All met together in England, united by their common goal of ending slavery in their time. Although abolitionism was not the largest American reform movement of the antebellum period (that honor belongs to temperance), it did foster greater cooperation among reformers in England and the United States.

除了传教工作外,反奴隶制运动从一开始就具有显著的跨大西洋性质。早在17世纪末,美国贵格会成员就开始质疑奴隶制,并与英国改革者合作,成功推动废除奴隶贸易。在美国革命前后,美国人始终对欧洲思想家心怀敬仰。这种影响是双向的。美国革命通过聚焦权利问题,激励了英国废奴主义者,而后者又为美国同行提供了支持。美国的反奴隶制活动家与跨大西洋的废奴主义者建立了密切的联系,如托马斯·克拉克森、丹尼尔·奥康奈尔和约瑟夫·斯特奇等人。美国著名废奴主义者西奥多·德怀特·韦尔德、卢克丽霞·莫特和威廉·劳埃德·加里森则受英国废奴主义者伊丽莎白·赫里克和查尔斯·斯图尔特的影响,接受了“立即废奴”的理念,即要求毫不拖延地解放奴隶。尽管英美反奴隶制网络可以追溯到18世纪末,但它们在南北战争前时期显著壮大,1840年的国际反奴隶制大会即是例证。这次大会吸引了500多名废奴主义者,主要来自法国、英国和美国。他们齐聚英国,共同致力于在自己的时代废除奴隶制。虽然废奴主义并非南北战争前时期美国规模最大的改革运动(这一称号属于禁酒运动),但它确实在英美改革者之间促成了更大的合作。

In the course of their abolitionist activities, many American women began to establish contact with their counterparts across the Atlantic, each group penning articles and contributing material support to the others’ antislavery publications and fundraisers. The bonds between British and American reformers can be traced throughout the many social improvement projects of the nineteenth century. Transatlantic cooperation galvanized efforts to reform individuals’ and societies’ relationships to alcohol, labor, religion, education, commerce, and land ownership. This cooperation stemmed from the recognition that social problems on both sides of the Atlantic were strikingly similar. Atlantic activists helped American reformers conceptualize themselves as part of a worldwide moral mission to attack social ills and spread the gospel of Christianity.

在废奴活动的过程中,许多美国女性开始与跨大西洋的同行建立联系,双方通过撰写文章和为对方的废奴出版物及募捐活动提供物质支持来相互合作。英美改革者之间的纽带贯穿了19世纪的许多社会改进项目。跨大西洋的合作激发了改革者们在酒精、劳动、宗教、教育、商业和土地所有权等领域推动社会关系改革的努力。这种合作源于对两岸社会问题惊人相似性的认识。大西洋两岸的活动家帮助美国改革者将自己视为全球道德使命的一部分,致力于解决社会弊病并传播基督教福音。

IV. The Benevolent Empire

四、仁爱帝国

After religious disestablishment, citizens of the United States faced a dilemma: how to cultivate a moral and virtuous public without aid from state-sponsored religion. Most Americans agreed that a good and moral citizenry was essential for the national project to succeed, but many shared the perception that society’s moral foundation was weakening. Narratives of moral and social decline, known as jeremiads, had long been embedded in Protestant story-telling traditions, but jeremiads took on new urgency in the antebellum period. In the years immediately following disestablishment, “traditional” Protestant Christianity was at low tide, while the Industrial Revolution and the spread of capitalism had led to a host of social problems associated with cities and commerce. The Second Great Awakening was in part a spiritual response to such changes, revitalizing Christian spirits through the promise of salvation. The revivals also provided an institutional antidote to the insecurities of a rapidly changing world by inspiring an immense and widespread movement for social reform. Growing directly out of nineteenth-century revivalism, reform societies proliferated throughout the United States between 1815 and 1861, melding religion and reform into a powerful force in American culture known as the benevolent empire.

在宗教脱离国教的背景下,美国公民面临着一个困境:如何在没有国家支持的宗教的帮助下,培养一个道德和有德行的公众。大多数美国人认为,良好的道德公民对于国家的成功至关重要,但许多人也认为社会的道德基础正在逐渐削弱。长期以来,被称为“警世哀叹”(jeremiads)的道德与社会衰退的叙事一直渗透在新教的故事传统中,而在前战争时期,“警世哀叹”的呼声变得更加迫切。在宗教脱离国教后的几年里,“传统的”新教基督教处于低谷,而工业革命和资本主义的扩展带来了许多与城市和商业相关的社会问题。第二次大觉醒在某种程度上是对这些变化的精神回应,通过救赎的承诺振奋了基督徒的精神。复兴运动也通过激发大规模的社会改革运动,提供了一种应对快速变化世界不安全感的制度性解药。改革社团从19世纪复兴主义中直接发展而来,并在1815至1861年间迅速蔓延,宗教与改革结合成一种在美国文化中具有强大影响力的力量,称为“仁爱帝国”。

The benevolent empire departed from revivalism’s early populism, as middle-class ministers dominated the leadership of antebellum reform societies. Because of the economic forces of the market revolution, middle-class evangelicals had the time and resources to devote to reform campaigns. Often, their reforms focused on creating and maintaining respectable middle-class culture throughout the United States. Middle-class women, in particular, played a leading role in reform activity. They became increasingly responsible for the moral maintenance of their homes and communities, and their leadership signaled a dramatic departure from previous generations when such prominent roles for ordinary women would have been unthinkable.

“仁爱帝国”脱离了早期复兴运动的平民主义特征,因为中产阶级牧师主导了前战争时期改革协会的领导工作。由于市场革命的经济力量,中产阶级的福音派基督徒有时间和资源专注于改革运动。通常,他们的改革侧重于在美国各地创建并维持体面的中产阶级文化。尤其是中产阶级女性,在改革活动中发挥了重要作用。她们越来越多地负责家庭和社区的道德维护,而她们的领导地位标志着与以往几代人截然不同的转变,以往普通女性在社会中担任如此重要的角色是不可想象的。

Different forces within evangelical Protestantism combined to encourage reform. One of the great lights of benevolent reform was Charles Grandison Finney, the radical revivalist, who promoted a movement known as “perfectionism.” Premised on the belief that truly redeemed Christians would be motivated to live free of sin and reflect the perfection of God himself, his wildly popular revivals encouraged his converted followers to join reform movements and create God’s kingdom on earth. The idea of “disinterested benevolence” also turned many evangelicals toward reform. Preachers championing disinterested benevolence argued that true Christianity requires that a person give up self-love in favor of loving others. Though perfectionism and disinterested benevolence were the most prominent forces encouraging benevolent societies, some preachers achieved the same end in their advocacy of postmillennialism. In this worldview, Christ’s return was foretold to occur after humanity had enjoyed one thousand years’ peace, and it was the duty of converted Christians to improve the world around them in order to pave the way for Christ’s redeeming return. Though ideological and theological issues like these divided Protestants into more and more sects, church leaders often worked on an interdenominational basis to establish benevolent societies and draw their followers into the work of social reform.

在福音派基督教内部,不同的力量共同推动了社会改革。仁爱改革的杰出人物之一是查尔斯·格兰迪森·芬尼(Charles Grandison Finney),这位激进的复兴主义者,倡导一种被称为“完美主义”的运动。该运动的基础是信仰,即真正得救的基督徒会受到激励,过上没有罪的生活,体现上帝本身的完美。他的复兴运动极受欢迎,鼓励他所转化的信徒加入改革运动,并在地球上建立上帝的国度。“无私仁爱”的思想也使许多福音派信徒倾向于参与改革。倡导无私仁爱的牧师认为,真正的基督教要求一个人放弃自爱,转而去爱他人。尽管完美主义和无私仁爱是推动仁爱协会的主要力量,一些牧师通过倡导后千禧年主义(postmillennialism)达成了相同的目的。在这种世界观中,基督的再来被预言将在人类享受一千年的和平之后发生,而得救的基督徒的责任是改善他们周围的世界,为基督的救赎之回归铺平道路。尽管像这些意识形态和神学问题将新教徒分裂成越来越多的教派,但教会领导人常常以跨教派的方式合作,建立仁爱协会,并将他们的信徒吸引到社会改革的工作中。

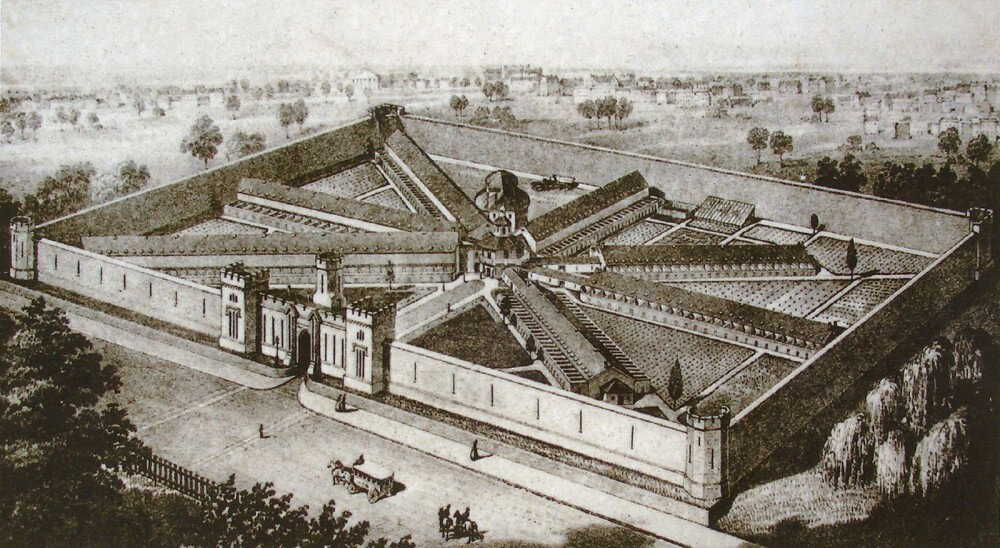

Under the leadership of preachers and ministers, reform societies attacked many social problems. Those concerned about drinking could join temperance societies; other groups focused on eradicating dueling and gambling. Evangelical reformers might support home or foreign missions or Bible and tract societies. Sabbatarians fought tirelessly to end nonreligious activity on the Sabbath. Moral reform societies sought to end prostitution and redeem “fallen women.” Over the course of the antebellum period, voluntary associations and benevolent activists also worked to reform bankruptcy laws, prison systems, insane asylums, labor laws, and education. They built orphanages and free medical dispensaries and developed programs to provide professional services like social work, job placement, and day camps for children in the slums.

在牧师和传教士的领导下,改革协会着手解决许多社会问题。那些关注饮酒问题的人可以加入禁酒协会;其他团体则专注于消除决斗和赌博。福音派改革者可能会支持国内或国外的传教工作,或支持圣经和布道书协会。守安息日的人不懈地努力结束安息日的非宗教活动。道德改革协会致力于结束卖淫,并拯救“堕落的女性”。在前南北战争时期,志愿性协会和仁爱活动家还致力于改革破产法、监狱制度、精神病院、劳动法和教育。他们建立了孤儿院和免费医疗诊所,并开发了提供专业服务的项目,如社会工作、职业介绍和贫民区儿童的日间营地。

These organizations often shared membership as individuals found themselves interested in a wide range of reform movements. On Anniversary Week, many of the major reform groups coordinated the schedules of their annual meetings in New York or Boston to allow individuals to attend multiple meetings in a single trip.

这些组织经常共享会员,因为人们通常对各种改革运动感兴趣。在周年纪念周期间,许多主要的改革团体协调了他们在纽约或波士顿的年会日程,以便让人们在一次旅行中参加多个会议。

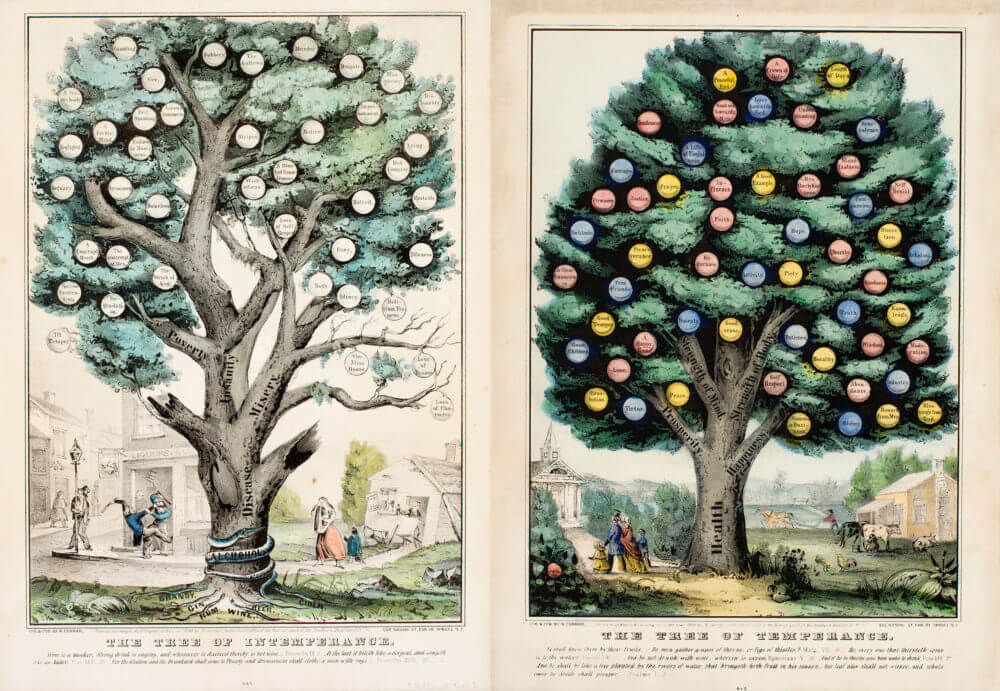

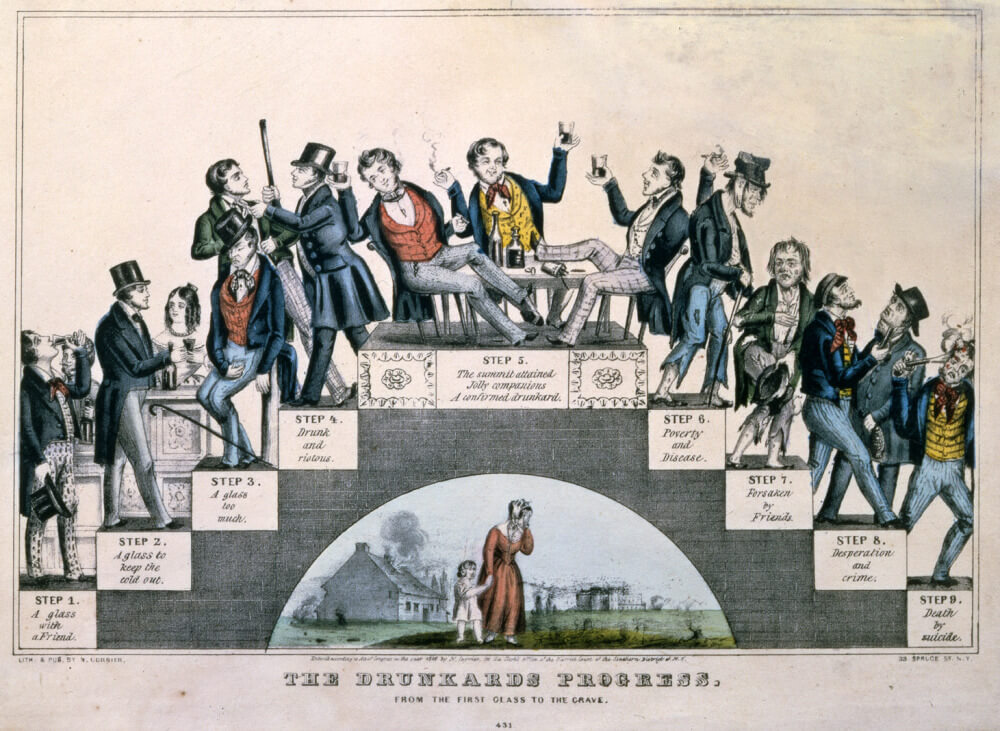

Among all the social reform movements associated with the benevolent empire, the temperance crusade was the most successful. Championed by prominent preachers like Lyman Beecher, the movement’s effort to curb the consumption of alcohol galvanized widespread support among the middle class. Alcohol consumption became a significant social issue after the American Revolution. Commercial distilleries produced readily available, cheap whiskey that was frequently more affordable than milk or beer and safer than water, and hard liquor became a staple beverage in many lower- and middle-class households. Consumption among adults skyrocketed in the early nineteenth century, and alcoholism had become an endemic problem across the United States by the 1820s. As alcoholism became an increasingly visible issue in towns and cities, most reformers escalated their efforts from advocating moderation in liquor consumption to full abstinence from all alcohol.

在所有与仁爱帝国相关的社会改革运动中,禁酒运动是最成功的。由莱曼·比彻(Lyman Beecher)等著名传教士倡导,这一运动旨在遏制酒精消费,迅速在中产阶级中获得了广泛支持。酒精消费在美国独立战争后成为了一个重要的社会问题。商业蒸馏厂生产了随时可以获得且价格低廉的威士忌,这些酒精饮品常常比牛奶或啤酒更便宜,且比水更安全,因此烈酒成为了许多低收入和中产阶级家庭的常备饮品。进入十九世纪初,成人的酒精消费激增,到1820年代,酗酒已经成为美国各地普遍存在的社会问题。随着酗酒问题在城镇和城市中愈发显眼,大多数改革者将他们的努力从提倡节制饮酒转向全面禁酒。

Many reformers saw intemperance as the biggest impediment to maintaining order and morality in the young republic. Temperance reformers saw a direct correlation between alcohol and other forms of vice and, most importantly, felt that it endangered family life. In 1826, evangelical ministers organized the American Temperance Society to help spread the crusade nationally. It supported lecture campaigns, produced temperance literature, and organized revivals specifically aimed at encouraging worshippers to give up the drink. It was so successful that within a decade, it established five thousand branches and grew to over a million members. Temperance reformers pledged not to touch the bottle and canvassed their neighborhoods and towns to encourage others to join their “Cold Water Army.” They also influenced lawmakers in several states to prohibit the sale of liquor.

许多改革者认为酗酒是维护年轻共和国秩序和道德的最大障碍。禁酒改革者认为酒精与其他形式的恶习之间有直接关联,最重要的是,他们认为酗酒危及家庭生活。1826年,福音派传教士组织了美国禁酒协会,旨在将这一运动推广到全国范围。该协会支持讲座活动,制作禁酒宣传资料,并组织复兴运动,特别是鼓励信徒放弃酒精。其成功程度如此之高,以至于在十年内,它建立了五千个分支机构,成员数量超过一百万。禁酒改革者誓言不碰酒瓶,积极走访邻里和城镇,鼓励他人加入他们的“冷水军”。他们还在多个州影响立法者禁止酒类销售。

In response to the perception that heavy drinking was associated with men who abused, abandoned, or neglected their family obligations, women formed a significant presence in societies dedicated to eradicating liquor. Temperance became a hallmark of middle-class respectability among both men and women and developed into a crusade with a visible class character. Temperance, like many other reform efforts, was championed by the middle class and threatened to intrude on the private lives of lower-class workers, many of whom were Irish Catholics. Such intrusions by the Protestant middle class exacerbated class, ethnic, and religious tensions. Still, while the temperance movement made less substantial inroads into lower-class workers’ drinking culture, the movement was still a great success for reformers. In the 1840s, Americans drank half of what they had in the 1820s, and per capita consumption continued to decline over the next two decades.

为了应对酗酒与虐待、抛弃或忽视家庭责任的男性之间的关联,女性在致力于消除酒精的社团中形成了重要力量。禁酒成为中产阶级尊严的标志,无论男性还是女性都将其视为一种象征,并且这一运动逐渐发展成具有明显阶级特征的运动。禁酒,像许多其他改革努力一样,受到了中产阶级的支持,但它威胁到对下层工人私人生活的干涉,而这些工人中的许多人是爱尔兰天主教徒。由新教中产阶级发起的这种干预加剧了阶级、种族和宗教的紧张关系。尽管禁酒运动在下层工人饮酒文化中取得的进展较为有限,但对于改革者来说,这一运动依然取得了巨大成功。到了1840年代,美国人的饮酒量已经是1820年代的一半,且人均饮酒量在接下来的二十年中持续下降。

Though middle-class reformers worked tirelessly to cure all manner of social problems through institutional salvation and voluntary benevolent work, they regularly participated in religious organizations founded explicitly to address the spiritual mission at the core of evangelical Protestantism. In fact, for many reformers, it was actually the experience of evangelizing among the poor and seeing firsthand the rampant social issues plaguing life in the slums that first inspired them to get involved in benevolent reform projects. Modeling themselves on the British and Foreign Bible Society, formed in 1804 to spread Christian doctrine to the British working class, urban missionaries emphasized the importance of winning the world for Christ, one soul at a time. For example, the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society used the efficient new steam-powered printing press to distribute Bibles and evangelizing religious tracts throughout the United States. For example, the New York Religious Tract Society alone managed to distribute religious tracts to all but 388 of New York City’s 28,383 families. In places like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, middle-class women also established groups specifically to canvass neighborhoods and bring the gospel to lower-class “wards.”

尽管中产阶级改革者孜孜不倦地通过制度化的救赎和志愿者仁爱工作来解决各种社会问题,他们也常常参与那些明确致力于传达福音的宗教组织,这些组织的宗旨正是响应新教福音派的核心精神使命。事实上,对于许多改革者来说,正是通过在贫困社区传教并亲眼目睹困扰贫民窟生活的社会问题,才激发了他们参与仁爱改革项目的热情。受英国与外籍圣经协会启发,该协会成立于1804年,旨在将基督教教义传播给英国工人阶级,城市传教士强调一次拯救一个灵魂的重要性,以此作为为基督赢得世界的使命。例如,美国圣经协会和美国小册子协会利用新型蒸汽动力印刷机有效地在美国各地分发圣经和传福音的小册子。例如,仅纽约宗教小册子协会就已将宗教小册子分发给了纽约市28,383户家庭中的大多数,仅有388户未能收到。在波士顿、纽约和费城等地,中产阶级女性也成立了专门的团体,走访社区,将福音传播到下层阶级的“区域”。

Such evangelical missions extended well beyond the urban landscape, however. Stirred by nationalism and moral purpose, evangelicals labored to make sure the word of God reached far-flung settlers on the new American frontier. The American Bible Society distributed thousands of Bibles to frontier areas where churches and clergy were scarce, while the American Home Missionary Society provided substantial financial assistance to frontier congregations struggling to achieve self-sufficiency. Missionaries worked to translate the Bible into Iroquois and other languages in order to more effectively evangelize Native American populations. As efficient printing technology and faster transportation facilitated new transatlantic and global connections, religious Americans also began to flex their missionary zeal on a global stage. In 1810, for example, Presbyterian and Congregationalist leaders established the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to evangelize in India, Africa, East Asia, and the Pacific.

然而,这些福音派的传教活动远远超出了城市范围。在民族主义和道德使命的激励下,福音派人士努力确保上帝的话语传递到遥远的美国边疆定居点。美国圣经协会向边远地区分发了成千上万的圣经,那些地方的教会和神职人员极为稀缺,而美国本土传教士协会则为努力实现自给自足的边疆教会提供了大量资金援助。传教士们还致力于将圣经翻译成易洛魁语等多种语言,以便更有效地向美洲原住民传播福音。随着印刷技术的进步和交通速度的提高,促进了新的跨大西洋和全球联系,宗教的美国人也开始在全球舞台上展现他们的传教热情。例如,1810年,长老会和公理会的领袖们成立了美国海外传教委员会,旨在印度、非洲、东亚和太平洋地区传播福音。

The potent combination of social reform and evangelical mission at the heart of the nineteenth century’s benevolent empire produced reform agendas and institutional changes that have reverberated through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. By devoting their time to the moral uplift of their communities and the world at large, middle-class reformers created many of the largest and most influential organizations in the nation’s history. For the optimistic, religiously motivated American, no problem seemed too great to solve.

十九世纪的“仁爱帝国”核心所在——社会改革与福音传教的有力结合,产生了影响深远的改革议程和制度变革,这些变革一直延续到二十世纪和二十一世纪。中产阶级改革者通过致力于提升他们的社区和整个世界的道德水平,创建了许多在美国历史上最庞大且最有影响力的组织。对于那些充满乐观和宗教动力的美国人来说,似乎没有什么问题是无法解决的。

Difficulties arose, however, when the benevolent empire attempted to take up more explicitly political issues. The movement against Indian removal was the first major example of this. Missionary work had first brought the Cherokee Nation to the attention of northeastern evangelicals in the early nineteenth century. Missionaries sent by the American Board and other groups sought to introduce Christianity and American cultural values to the Cherokee and celebrated when their efforts seemed to be met with success. Evangelicals proclaimed that the Cherokee were becoming “civilized,” which could be seen in their adoption of a written language and of a constitution modeled on that of the U.S. government. Mission supporters were shocked, then, when the election of Andrew Jackson brought a new emphasis on the removal of Native Americans from the land east of the Mississippi River. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was met with fierce opposition from within the affected Native American communities as well as from the benevolent empire. Jeremiah Evarts, one of the leaders of the American Board, wrote a series of essays under the pen name William Penn urging Americans to oppose removal. He used the religious and moral arguments of the mission movement but added a new layer of politics in his extensive discussion of the history of treaty law between the United States and Native Americans. This political shift was even more evident when American missionaries challenged Georgia state laws asserting sovereignty over Cherokee territory in the Supreme Court Case Worcester v. Georgia. Although the case was successful, the federal government did not enforce the Court’s decision, and Indian removal was accomplished through the Trail of Tears, the tragic, forced removal of Native Americans to territories west of the Mississippi River.

然而,当“仁爱帝国”试图处理更具政治性质的问题时,困难便随之而来。反对印第安人迁移的运动便是这一点的首个重要例子。早在十九世纪初,传教工作就将切诺基民族引起了美国东北部福音派人士的关注。美国传教协会等团体派遣的传教士试图将基督教和美国文化价值观传入切诺基,并为他们的努力似乎取得的成功而庆祝。福音派宣称切诺基正在变得“文明”,这可以通过他们采纳书面语言和仿照美国政府宪法的方式来体现。然而,当安德鲁·杰克逊当选为总统后,出现了更加强调将美洲原住民从密西西比河以东地区迁移的政策,支持传教事业的人们感到震惊。1830年的《印第安迁移法案》遭到了受影响的美洲原住民社区以及“仁爱帝国”内部的激烈反对。美国传教协会的领导人之一杰里迈亚·厄沃茨以“威廉·潘”这一笔名写了一系列文章,呼吁美国人反对迁移。他在传教运动的宗教和道德论点的基础上,增加了对美国与美洲原住民之间条约法历史的广泛讨论,提出了新的政治层面的论证。当美国传教士挑战乔治亚州关于切诺基领土主权的法律,并在《沃斯特诉乔治亚州》一案中向最高法院提起诉讼时,这一政治转变变得更加明显。尽管案件最终胜诉,联邦政府并未执行法院判决,印第安人迁移还是通过“眼泪之路”得以实施,这一悲剧性的强制迁移将美洲原住民送往密西西比河以西的领土。

Anti-removal activism was also notable for the entry of ordinary American women into political discourse. The first major petition campaign by American women focused on opposition to removal and was led (anonymously) by Catharine Beecher. Beecher was already a leader in the movement to reform women’s education and came to her role in removal through her connections to the mission movement. Inspired by a meeting with Jeremiah Evarts, Beecher echoed his arguments from the William Penn letters in her appeal to American women. Beecher called on women to petition the government to end the policy of Indian removal. She used religious and moral arguments to justify women’s entry into political discussion when it concerned an obviously moral cause. This effort was ultimately unsuccessful but still introduced the kinds of arguments that paved the way for women’s political activism for abolitionism and women’s rights. The divisions that the anti-removal campaign revealed became more dramatic with the next political cause of nineteenth century reformers: abolitionism.

反对迁移的活动也以普通美国女性进入政治话语而引人注目。美国女性的首次重大请愿运动便是反对印第安人迁移,而该运动由凯瑟琳·比彻(Catharine Beecher)领导(她匿名参与)。比彻当时已经是女性教育改革运动的领导者,通过与传教运动的联系,她开始关注反对印第安人迁移的问题。受杰里迈亚·厄沃茨启发,比彻在她的呼吁中回响了“威廉·潘”信件中的论点,号召美国女性请愿政府结束印第安人迁移政策。她通过宗教和道德论据来为女性进入政治讨论辩护,特别是在涉及明显的道德事业时。尽管这一努力最终未能成功,但它仍然提出了为废奴主义和女性权利运动铺路的论点。反对迁移运动暴露出的分歧,在十九世纪改革者们的下一个政治事业——废奴主义中,变得更加剧烈。

V. Antislavery and Abolitionism

五、废奴主义与废奴运动

The revivalist doctrines of salvation, perfectionism, and disinterested benevolence led many evangelical reformers to believe that slavery was the most God-defying of all sins and the most terrible blight on the moral virtue of the United States. While white interest in and commitment to abolition had existed for several decades, organized antislavery advocacy had been largely restricted to models of gradual emancipation (seen in several northern states following the American Revolution) and conditional emancipation (seen in colonization efforts to remove Black Americans to settlements in Africa). The colonizationist movement of the early nineteenth century had drawn together a broad political spectrum of Americans with its promise of gradually ending slavery in the United States by removing the free Black population from North America. By the 1830s, however, a rising tide of anticolonization sentiment among northern free Black Americans and middle-class evangelicals’ flourishing commitment to social reform radicalized the movement. Baptists such as William Lloyd Garrison, Congregational revivalists like Arthur and Lewis Tappan and Theodore Dwight Weld, and radical Quakers including Lucretia Mott and John Greenleaf Whittier helped push the idea of immediate emancipation onto the center stage of northern reform agendas. Inspired by a strategy known as “moral suasion,” these young abolitionists believed they could convince enslavers to voluntarily release their enslaved laborers by appealing to their sense of Christian conscience. The result would be national redemption and moral harmony.

复兴主义的救赎、完美主义和无私仁爱学说使许多福音派改革者认为,奴隶制是所有罪行中最背离上帝的,是美国道德美德的最大污点。尽管白人对废奴的关注和承诺已经存在了数十年,但有组织的废奴倡导在很大程度上仍局限于渐进解放的模式(在美国革命后几个北方州实施)和有条件解放的模式(如将黑人美国人迁往非洲定居点的殖民化努力)。十九世纪初的殖民主义运动通过承诺通过将自由黑人从北美移除,逐步结束美国的奴隶制,吸引了广泛的政治光谱。但到了1830年代,北方自由黑人群体的反殖民情绪上升,加上中产阶级福音派改革者日益增长的社会改革承诺,推动了该运动的激进化。像威廉·劳埃德·加里森这样的浸信会教徒,亚瑟和刘易斯·塔潘以及西奥多·德怀特·韦尔德等公理会复兴派,和如卢克丽霞·莫特与约翰·格林利夫·惠蒂尔等激进的贵格会成员,共同推动了即刻解放的思想,成为北方改革议程的核心。受到名为“道德劝说”的策略启发,这些年轻的废奴主义者认为,他们能够通过呼吁奴隶主的基督教良知,促使他们自愿释放被奴役的劳动者。其结果将是国家的救赎与道德的和谐。

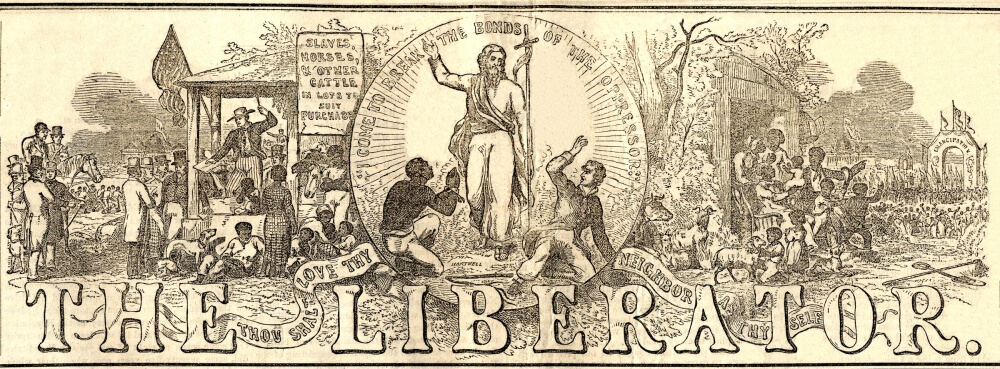

William Lloyd Garrison’s early life and career famously illustrated this transition toward immediatism. As a young man immersed in the reform culture of antebellum Massachusetts, Garrison had fought slavery in the 1820s by advocating for both Black colonization and gradual abolition. Fiery tracts penned by Black northerners David Walker and James Forten, however, convinced Garrison that colonization was an inherently racist project and that African Americans possessed a hard-won right to the fruits of American liberty. So, in 1831, he established a newspaper called The Liberator, through which he organized and spearheaded an unprecedented interracial crusade dedicated to promoting immediate emancipation and Black citizenship. Then, in 1833, Garrison presided as reformers from ten states came together to create the American Anti-Slavery Society. They rested their mission for immediate emancipation “upon the Declaration of our Independence, and upon the truths of Divine Revelation,” binding their cause to both national and Christian redemption. Abolitionists fought to save the enslaved and thereby save the nation.

威廉·劳埃德·加里森的早期生活和职业生涯充分展示了向即时解放主义过渡的过程。作为一名沉浸在南北战争前马萨诸塞州改革文化中的年轻人,加里森在1820年代通过倡导黑人殖民和渐进解放来反对奴隶制。然而,北方黑人大卫·沃克和詹姆斯·福尔顿撰写的激烈小册子使加里森深信殖民化本质上是一个种族主义项目,非裔美国人拥有争取美国自由果实的合法权利。因此,在1831年,他创办了《解放者》报,并通过这份报纸组织并领导了一场前所未有的跨种族运动,致力于促进即时解放和黑人公民身份。随后,在1833年,加里森主持了来自十个州的改革者们联合创建美国废奴协会的大会。他们将即时解放的使命“基于我们独立宣言的原则和神圣启示的真理”,将他们的事业与国家和基督教的救赎紧密相连。废奴主义者们为了解救被奴役者,也为了解救国家而战。

In order to accomplish their goals, abolitionists employed every method of outreach and agitation. At home in the North, abolitionists established hundreds of antislavery societies and worked with long-standing associations of Black activists to establish schools, churches, and voluntary associations. Women and men of all colors were encouraged to associate together in these spaces to combat what they termed “color phobia.” Harnessing the potential of steam-powered printing and mass communication, abolitionists also blanketed the free states with pamphlets and antislavery newspapers. They blared their arguments from lyceum podiums and broadsides. Prominent individuals such as Wendell Phillips and Angelina Grimké saturated northern media with shame-inducing exposés of northern complicity in the return of freedom-seeking fugitive enslaved people, and white reformers sentimentalized slave narratives that tugged at middle-class heartstrings. Abolitionists used the U.S. Postal Service in 1835 to inundate southern enslavers with calls to emancipate their enslaved laborers in order to save their souls, and, in 1836, they prepared thousands of petitions for Congress as part of the Great Petition Campaign. In the six years from 1831 to 1837, abolitionist activities reached dizzying heights.

为了实现他们的目标,废奴主义者采取了各种方式进行宣传和激进行动。在北方,废奴主义者建立了数百个废奴协会,并与长期存在的黑人活动家组织合作,建立学校、教堂和志愿者协会。男女各色人种被鼓励共同参与这些空间,以应对他们所称之为的“种族恐惧症”。利用蒸汽印刷机和大众传播的潜力,废奴主义者还向自由州散发小册子和废奴报纸。他们通过讲坛和大幅宣传单张大声宣扬他们的观点。像温德尔·菲利普斯和安吉丽娜·格里姆凯这样的著名人物,通过揭露北方在帮助自由逃亡奴隶方面的共谋,向北方媒体输送令人羞愧的报道;而白人改革者则感情化地宣扬奴隶叙事,触动中产阶级的心弦。废奴主义者还利用美国邮政局在1835年向南方的奴隶主发送要求解放奴隶的信件,呼吁他们解救奴隶劳工的灵魂;并在1836年为国会准备了成千上万份请愿书,作为“大请愿运动”的一部分。在1831到1837年的六年间,废奴活动达到了令人眼花缭乱的高度。

However, such efforts encountered fierce opposition, as most Americans did not share abolitionists’ particular brand of nationalism. In fact, abolitionists remained a small, marginalized group detested by most white Americans in both the North and the South. Immediatists were attacked as the harbingers of disunion, rabble-rousers who would stir up sectional tensions and thereby imperil the American experiment of self-government. Particularly troubling to some observers was the public engagement of women as abolitionist speakers and activists. Fearful of disunion and outraged by the interracial nature of abolitionism, northern mobs smashed abolitionist printing presses and even killed a prominent antislavery newspaper editor named Elijah Lovejoy. White southerners, believing that abolitionists had incited Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831, aggressively purged antislavery dissent from the region. Violent harassment threatened abolitionists’ personal safety. In Congress, Whigs and Democrats joined forces in 1836 to pass an unprecedented restriction on freedom of political expression known as the gag rule, prohibiting all discussion of abolitionist petitions in the House of Representatives. Two years later, mobs attacked the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women, throwing rocks through the windows and burning the newly constructed Pennsylvania Hall to the ground.

然而,这些努力遭遇了激烈的反对,因为大多数美国人并不认同废奴主义者所持的特定民族主义观念。事实上,废奴主义者始终是一个小众的、被大多数北方和南方白人所憎恶的群体。立即解放主义者被攻击为分裂的先驱者,是煽动者,他们会激化地区间的紧张局势,从而危及美国自我治理的实验。尤其让一些观察者感到困扰的是女性公开参与成为废奴演讲者和活动家的角色。由于担心国家分裂并愤怒于废奴主义的跨种族性质,北方的暴徒摧毁了废奴主义者的印刷厂,甚至杀害了一位著名的废奴报纸编辑埃利贾·洛夫乔伊。白人南方人认为废奴主义者煽动了1831年的纳特·特纳起义,便在该地区积极清除废奴异见。暴力骚扰威胁到废奴主义者的个人安全。在国会中,1836年,辉格党和民主党联合通过了一项前所未有的限制政治言论自由的规定——“言论禁令”,禁止在众议院讨论任何废奴主义者的请愿。两年后,暴徒袭击了美国女性废奴大会,投掷石块打破窗户,并将新建的宾夕法尼亚大厅焚毁。

In the face of such substantial external opposition, the abolitionist movement began to splinter. In 1839, an ideological schism shook the foundations of organized antislavery. Moral suasionists, led most prominently by William Lloyd Garrison, felt that the U.S. Constitution was a fundamentally pro-slavery document, and that the present political system was irredeemable. They dedicated their efforts exclusively toward persuading the public to redeem the nation by reestablishing it on antislavery grounds. However, many abolitionists, reeling from the level of entrenched opposition met in the 1830s, began to feel that moral suasion was no longer realistic. Instead, they believed, abolition would have to be effected through existing political processes. So, in 1839, political abolitionists formed the Liberty Party under the leadership of James G. Birney. This new abolitionist society was predicated on the belief that the U.S. Constitution was actually an antislavery document that could be used to abolish the stain of slavery through the national political system.

面对如此巨大的外部反对,废奴主义运动开始分裂。1839年,一场意识形态上的分裂动摇了有组织的废奴基础。道德劝说主义者,由威廉·劳埃德·加里森为首,认为美国宪法本质上是支持奴隶制的,当前的政治体系是无法挽救的。他们将努力专注于说服公众通过反奴隶制的立场来拯救国家。然而,许多废奴主义者在经历了1830年代遭遇的强烈反对后,开始认为道德劝说已不再现实。相反,他们认为,废奴必须通过现有的政治过程来实现。因此,1839年,政治废奴主义者在詹姆斯·吉·伯尼的领导下成立了自由党。这个新的废奴社会建立在一个信念上:即美国宪法实际上是一个反奴隶制的文件,可以通过国家政治体系来消除奴隶制的污点。

Women’s rights, too, divided abolitionists. Many abolitionists who believed full-heartedly in moral suasion nonetheless felt compelled to leave the American Anti-Slavery Society because, in part, it elevated women to leadership positions and endorsed women’s suffrage. This question came to a head when, in 1840, Abby Kelly was elected to the business committee of the society. The elevation of women to full leadership roles was too much for some conservative members who saw this as evidence that the society had lost sight of its most important goal. Under the leadership of Arthur Tappan, they left to form the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. These disputes became so bitter and acrimonious that former friends cut social ties and traded public insults.

女性权利问题同样使废奴主义者分裂。许多废奴主义者虽然全心全意地支持道德劝说,但仍然感到有必要离开美国废奴协会,部分原因是该协会将女性提升至领导职位,并支持女性选举权。当1840年艾比·凯利(Abby Kelly)被选为协会事务委员会成员时,这个问题达到了高潮。将女性提升为完全的领导角色对于一些保守成员来说太过分了,他们认为这是协会偏离其最重要目标的标志。在阿瑟·塔潘(Arthur Tappan)的领导下,他们脱离了协会,成立了美洲与外国废奴协会。这些争执变得如此尖锐和激烈,以至于曾经的朋友切断了社交联系,互相公开侮辱。

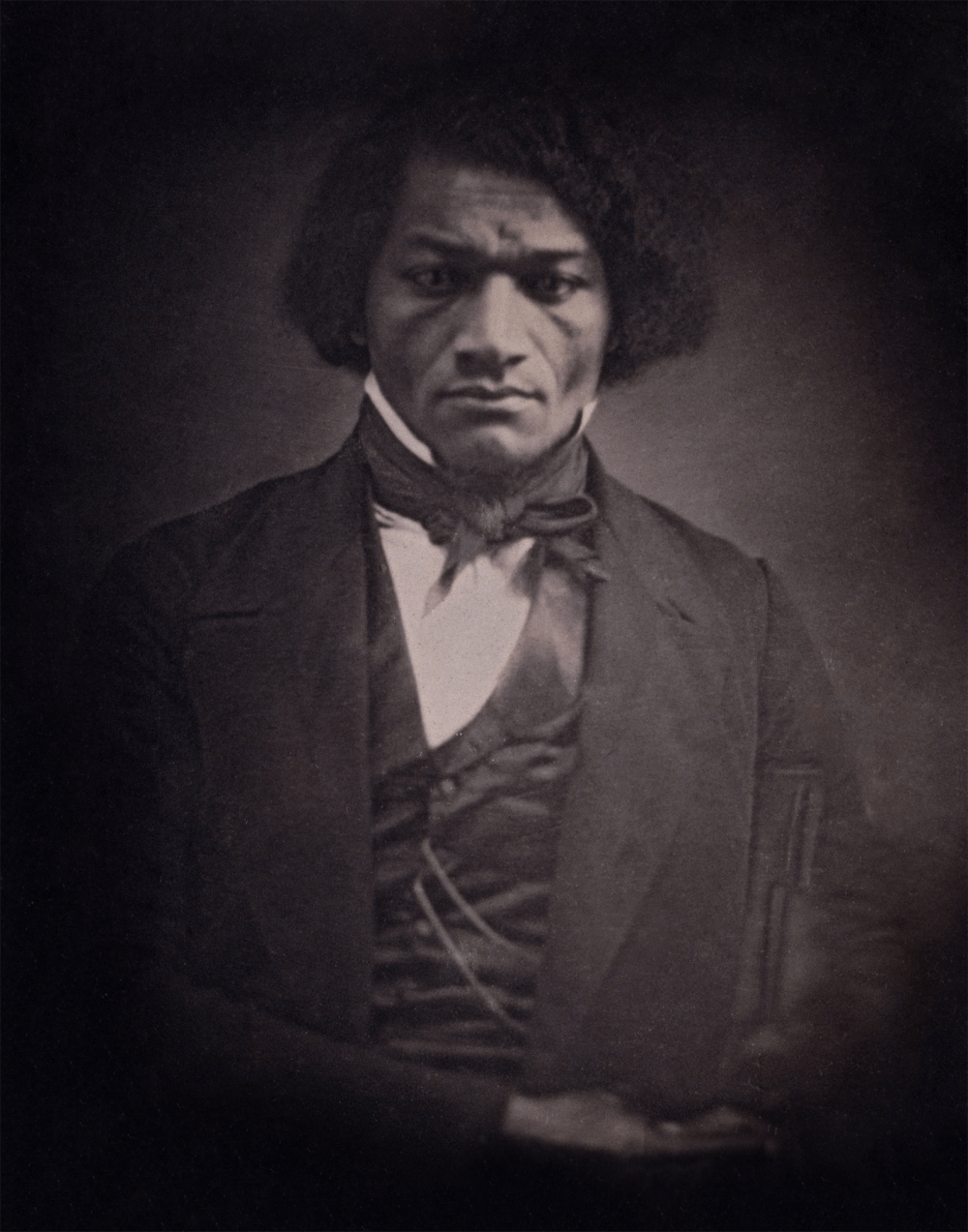

Another significant shift stemmed from the disappointments of the 1830s. Abolitionists in the 1840s increasingly moved from agendas based on reform to agendas based on resistance. Moral suasionists continued to appeal to hearts and minds, and political abolitionists launched sustained campaigns to bring abolitionist agendas to the ballot box. Meanwhile the entrenched and violent opposition of both enslavers and the northern public encouraged abolitionists to find other avenues of fighting the slave power. Increasingly, for example, abolitionists aided runaway enslaved people and established international antislavery networks to pressure the United States to abolish slavery. Frederick Douglass represented the intersection of these two trends. After escaping from slavery, Douglass came to the fore of the abolitionist movement as a naturally gifted orator and a powerful narrator of his experiences in slavery. His first autobiography, published in 1845, was so widely read that it was reprinted in nine editions and translated into several languages. Douglass traveled to Great Britain in 1845 and met with famous British abolitionists like Thomas Clarkson, drumming up moral and financial support from British and Irish antislavery societies. His great success abroad contributed significantly to rousing morale among weary abolitionists at home.

另一个重要的转变源于1830年代的失望。废奴主义者在1840年代越来越多地从基于改革的议程转向了基于抵抗的议程。道德劝说主义者继续向人们的心灵和理性呼吁,而政治废奴主义者则发起了持续的运动,将废奴议程带入选举投票箱。与此同时,奴隶主和北方公众的根深蒂固且暴力的反对,促使废奴主义者寻找其他途径来对抗奴隶制度的势力。例如,废奴主义者越来越多地帮助逃亡的奴隶,并建立了国际废奴网络,向美国施压要求废除奴隶制度。弗雷德里克·道格拉斯(Frederick Douglass)代表了这两种趋势的交汇点。在逃离奴隶制度后,道格拉斯凭借天生的演讲才能和对自己在奴隶制中经历的生动叙述,迅速成为废奴运动的领袖之一。他的第一本自传《奴隶生涯》于1845年出版,广受欢迎,迅速再版九次,并被翻译成多种语言。道格拉斯于1845年赴英国,结识了像托马斯·克拉克森(Thomas Clarkson)等著名的英国废奴主义者,并从英国和爱尔兰的废奴协会筹集道德和财政支持。他在国外的巨大成功为国内疲惫的废奴主义者带来了极大的鼓舞。

The model of resistance to the slave power only became more pronounced after 1850, when a long-standing Fugitive Slave Act was given new teeth. Though a legal mandate to return runaway enslaved people had existed in U.S. federal law since 1793, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 upped the ante by harshly penalizing officials who failed to arrest runaways and private citizens who tried to help them. This law, coupled with growing concern over the possibility that slavery would be allowed in Kansas when it was admitted as a state, made the 1850s a highly volatile and violent period of American antislavery. Reform took a backseat as armed mobs protected freedom-seeking enslaved people in the North and fortified abolitionists engaged in bloody skirmishes in the West. Culminating in John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, the violence of the 1850s convinced many Americans that the issue of slavery was pushing the nation to the brink of sectional cataclysm. After two decades of immediatist agitation, the idealism of revivalist perfectionism had given way to a protracted battle for the moral soul of the country.

抵抗奴隶制度的模式在1850年后变得更加明显,那时长期存在的《逃奴法》得到了更严格的执行。虽然自1793年以来,美国联邦法律就有强制返还逃亡奴隶的规定,但1850年的《逃奴法》则通过严厉惩罚未能逮捕逃奴的官员以及试图帮助逃奴的私人公民,进一步加剧了这一法律的执行力度。这项法律,再加上对奴隶制可能在堪萨斯州被允许的担忧,使得1850年代成为美国废奴运动中极为动荡和暴力的时期。改革逐渐退居其次,武装暴徒在北方保护寻求自由的逃奴,废奴主义者在西部进行血腥的小规模战斗。最终,约翰·布朗(John Brown)袭击哈珀斯渡口的事件标志着1850年代暴力的顶峰,这一系列暴力事件让许多美国人相信,奴隶制问题正在将国家推向区域性灾难的边缘。在经历了二十年的即时废奴主义运动后,复兴完美主义的理想主义让位于一场关于国家道德灵魂的持久斗争。

For all of the problems that abolitionism faced, the movement was far from a failure. The prominence of African Americans in abolitionist organizations offered a powerful, if imperfect, model of interracial coexistence. While immediatists always remained a minority, their efforts paved the way for the moderately antislavery Republican Party to gain traction in the years preceding the Civil War. It is hard to imagine that Abraham Lincoln could have become president in 1860 without the ground prepared by antislavery advocates and without the presence of radical abolitionists against whom he could be cast as a moderate alternative. Though it ultimately took a civil war to break the bonds of slavery in the United States, the evangelical moral compass of revivalist Protestantism provided motivation for the embattled abolitionists.

尽管废奴主义面临诸多困难,但这一运动远未失败。非裔美国人在废奴组织中的突出地位,提供了一个强大的(尽管不完美的)种族间共存模式。虽然即时废奴主义者始终是少数派,但他们的努力为温和废奴的共和党在内战前的几年赢得了支持。很难想象,在没有废奴倡导者所奠定的基础,也没有激进废奴主义者的存在,让亚伯拉罕·林肯(Abraham Lincoln)在1860年当选为总统会有多么容易。虽然最终需要通过一场内战才能打破美国的奴隶制度,但复兴派新教的道德指南针为奋战中的废奴主义者提供了动力。

VI. Women’s Rights in Antebellum America

六、内战前美国的妇女权利

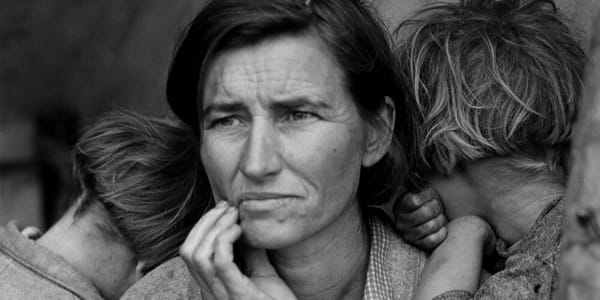

In the era of revivalism and reform, Americans understood the family and home as the hearthstones of civic virtue and moral influence. This increasingly confined middle-class white women to the domestic sphere, where they were responsible for educating children and maintaining household virtue. Yet women took the very ideology that defined their place in the home and managed to use it to fashion a public role for themselves. As a result, women actually became more visible and active in the public sphere than ever before. The influence of the Second Great Awakening, coupled with new educational opportunities available to girls and young women, enabled white middle-class women to leave their homes en masse, joining and forming societies dedicated to everything from literary interests to the antislavery movement.

在复兴与改革的时代,美国人认为家庭和家庭生活是公民美德和道德影响的基石。这种观念将中产阶级白人女性越来越局限于家庭领域,负责教育孩子和维护家庭的道德。然而,女性们却利用这种定义她们在家庭中角色的意识形态,成功地为自己创造了一个公共角色。因此,女性实际上比以往任何时候都更加活跃和显现于公共领域。第二次大觉醒的影响,加上女孩和年轻女性获得的新教育机会,使得白人中产阶级女性大规模地走出家门,加入并成立了从文学兴趣到废奴运动等各类社团。

In the early nineteenth century, the dominant understanding of gender claimed that women were the guardians of virtue and the spiritual heads of the home. Women were expected to be pious, pure, submissive, and domestic, and to pass these virtues on to their children. Historians have described these expectations as the “Cult of Domesticity,” or the “Cult of True Womanhood,” and they developed in tandem with industrialization, the market revolution, and the Second Great Awakening. These economic and religious transformations increasingly seemed to divide the world into the public space of work and politics and the domestic space of leisure and morality. Voluntary work related to labor laws, prison reform, and antislavery applied women’s roles as guardians of moral virtue to address all forms of social issues that they felt contributed to the moral decline of society. In spite of this apparent valuation of women’s position in society, there were clear limitations. Under the terms of coverture, men gained legal control over their wives’ property, and women with children had no legal rights over their offspring. Additionally, women could not initiate divorce, make wills, sign contracts, or vote.

在19世纪初,主流的性别观念认为女性是美德的守护者和家庭的精神领袖。女性被期望是虔诚的、纯洁的、顺从的,并且要将这些美德传递给孩子们。历史学家将这些期望称为“家庭神圣化”或“真正女性的神圣化”,它们与工业化、市场革命和第二次大觉醒同步发展。这些经济和宗教的变革逐渐使世界分为公共领域的工作和政治,以及家庭领域的休闲和道德。与劳动法、监狱改革和废奴相关的志愿工作,将女性作为道德美德的守护者这一角色应用于解决所有她们认为导致社会道德衰退的社会问题。尽管在表面上女性的社会地位得到重视,但仍然存在明显的局限性。在“共同约定”的条款下,男性获得了对妻子财产的法律控制权,而有子女的女性对其后代没有法律权利。此外,女性不能发起离婚、立遗嘱、签订合同或投票。

Female education provides an example of the great strides made by and for women during the antebellum period. As part of a larger education reform movement in the early republic, several female reformers worked tirelessly to increase women’s access to education. They argued that if women were to take charge of the education of their children, they needed to be well educated themselves. While the women’s education movement did not generally push for women’s political or social equality, it did assert women’s intellectual equality with men, an idea that would eventually have important effects. Educators such as Emma Willard, Catharine Beecher, and Mary Lyon (founders of the Troy Female Seminary, Hartford Female Seminary, and Mount Holyoke Seminary, respectively) adopted the same rigorous curriculum that was used for boys. Many of these schools had the particular goal of training women to be teachers. Many graduates of these prominent seminaries would found their own schools, spreading women’s education across the country, and with it ideas about women’s potential to take part in public life.

女性教育是前战争时期女性在各个领域取得的重要进展之一。作为早期美国教育改革运动的一部分,几位女性改革者不懈努力,增加女性接受教育的机会。她们认为,如果女性要负责教育自己的孩子,那么她们自己必须接受良好的教育。尽管女性教育运动通常没有主张女性的政治或社会平等,但它确实主张女性在智力上与男性平等,这一观点最终会产生重要影响。像艾玛·威拉德、凯瑟琳·比彻和玛丽·莱昂等教育家(分别创办了特洛伊女性中学、哈特福德女性中学和霍利奥克女子中学)采用了与男孩一样严格的课程。许多这些学校的特别目标是培养女性成为教师。许多来自这些著名中学的毕业生会创办自己的学校,推动女性教育在全国范围内的发展,同时也传播了关于女性有能力参与公共生活的思想。

The abolitionist movement was another important school for women’s public engagement. Many of the earliest women’s rights advocates began their activism by fighting the injustices of slavery, including Angelina and Sarah Grimké, Lucretia Mott, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. In the 1830s, women in cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia established female societies dedicated to the antislavery cause. Initially, these societies were similar to the prayer and fund-raising-based projects of other reform societies. As such societies proliferated, however, their strategies changed. Women could not vote, for example, but they increasingly used their right to petition to express their antislavery grievances to the government. Impassioned women like the Grimké sisters even began to travel on lecture circuits. This latter strategy, born of fervent antislavery advocacy, ultimately tethered the cause of women’s rights to abolitionism.

废奴运动是女性公共参与的重要学校。许多最早的女性权利倡导者开始通过反对奴隶制的不公正现象来展开她们的行动,包括安吉丽娜·格里姆凯、萨拉·格里姆凯、卢克丽霞·莫特、索杰纳·特鲁斯、伊丽莎白·凯迪·斯坦顿和苏珊·安东尼。在19世纪30年代,波士顿、纽约和费城等城市的女性建立了致力于反奴隶制事业的女性社团。最初,这些社团类似于其他改革社团的祈祷和募捐项目。然而,随着这类社团的增多,它们的策略发生了变化。例如,女性无法投票,但她们越来越多地利用请愿权向政府表达她们对废奴事业的不满。像格里姆凯姐妹这样的激情四溢的女性甚至开始参加演讲巡回活动。这一策略源于对废奴的热情倡导,最终将女性权利的事业与废奴主义紧密相连。

Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké were born to a wealthy family in Charleston, South Carolina, where they witnessed the horrors of slavery firsthand. Repulsed by the treatment of the enslaved laborers on the Grimké plantation, they decided to support the antislavery movement by sharing their experiences on northern lecture tours. At first speaking to female audiences, they soon attracted “promiscuous” crowds of both men and women. They were among the earliest and most famous American women to take such a public role in the name of reform. When the Grimké sisters met substantial harassment and opposition to their public speaking on antislavery, they were inspired to speak out against more than the slave system. They began to see that they would need to fight for women’s rights in order to fight for the rights of enslaved people. Other female abolitionists soon joined them in linking the issues of women’s rights and abolitionism by drawing direct comparisons between the condition of free women in the United States and the condition of the slave.

萨拉·摩尔·格里姆凯和安吉丽娜·埃米莉·格里姆凯出生在南卡罗来纳州查尔斯顿的一个富裕家庭,她们亲眼目睹了奴隶制的恐怖。由于对格里姆凯种植园上奴隶劳工待遇的反感,她们决定通过分享自己在北方的讲学经历来支持废奴运动。最初,她们只向女性观众演讲,但很快吸引了男女混杂的听众。她们是最早和最著名的美国女性之一,在改革的名义下采取如此公开的角色。当格里姆凯姐妹遇到大量的骚扰和反对,尤其是她们公开演讲反对奴隶制时,她们受到启发,开始不仅反对奴隶制度。她们意识到,只有为女性争取权利,才能真正为奴隶争取权利。其他女性废奴主义者很快也加入她们的行列,将女性权利与废奴主义的事业联系起来,通过直接对比自由女性在美国的处境和奴隶的境遇。

As the antislavery movement gained momentum in northern states in the 1830s and 1840s, so too did efforts for women’s rights. These efforts came to a head at an event that took place in London in 1840. That year, Lucretia Mott was among the American delegates attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Because of ideological disagreements between some of the abolitionists, the convention’s organizers refused to seat the female delegates or allow them to vote during the proceedings. Angered by such treatment, Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, whose husband was also a delegate, returned to the United States with a renewed interest in pursuing women’s rights. In 1848, they organized the Seneca Falls Convention, a two-day summit in New York state in which women’s rights advocates came together to discuss the problems facing women.

随着废奴运动在19世纪30年代和40年代在北方各州取得进展,女性权利运动也开始获得关注。这一努力在1840年伦敦举办的一次事件中达到了高潮。那一年,卢克丽霞·莫特是参加世界废奴大会的美国代表之一。由于一些废奴主义者之间的意识形态分歧,大会组织者拒绝给女性代表安排座位或让她们在大会期间投票。莫特和伊丽莎白·凯迪·斯坦顿(她丈夫也是代表之一)对这种待遇感到愤怒,并带着对女性权利的新兴趣返回美国。1848年,她们组织了塞内卡福尔斯大会,这是在纽约州举行的为期两天的会议,女性权利倡导者们聚集在一起,讨论女性所面临的问题。

Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments for the Seneca Falls Convention to capture the wide range of issues embraced by the early women’s rights movement. She modeled the document on the Declaration of Independence to make explicit the connection between women’s liberty and the rhetoric of America’s founding. The Declaration of Sentiments outlined fifteen grievances and eleven resolutions. They championed property rights, access to the professions, and, most controversially, the right to vote. Sixty-eight women and thirty-two men, all of whom were already involved in some aspect of reform, signed the Declaration of Sentiments.

斯坦顿为塞内卡福尔斯大会撰写了《情感宣言》,旨在概括早期女性权利运动所涉及的广泛问题。她模仿《独立宣言》来明确女性自由与美国建国言辞之间的联系。《情感宣言》列出了十五项诉求和十一项决议,主张财产权、职业准入,最具争议的则是选举权。68名女性和32名男性(他们都已参与某种形式的改革)签署了《情感宣言》。

Antebellum women’s rights fought what they perceived as senseless gender discrimination, such as the barring of women from college and inferior pay for female teachers. They also argued that men and women should be held to the same moral standards. The Seneca Falls Convention was the first of many such gatherings promoting women’s rights, held almost exclusively in the northern states. Yet the women’s rights movement grew slowly and experienced few victories. Few states reformed married women’s property laws before the Civil War, and no state was prepared to offer women the right to vote during the antebellum period. At the onset of the Civil War, women’s rights advocates temporarily threw the bulk of their support behind abolition, allowing the cause of racial equality to temporarily trump that of gender equality. But the words of the Seneca Falls convention continued to inspire generations of activists.

在南北战争前的女性权利运动中,女性反对她们所感受到的毫无意义的性别歧视,例如禁止女性上大学以及女性教师收入低廉等问题。她们还主张,男性和女性应当被要求遵守相同的道德标准。塞内卡福尔斯大会是为女性权利举办的第一次会议,类似的大会几乎全部在北方各州举行。然而,女性权利运动发展缓慢,取得的胜利寥寥。南北战争前,只有少数几个州对已婚女性的财产法进行了改革,而在整个南北战争前期,没有哪个州准备赋予女性选举权。尽管如此,塞内卡福尔斯大会的言辞依然激励着一代又一代的活动家。

VII. Conclusion

七、结论

By the time civil war erupted in 1861, the revival and reform movements of the antebellum period had made an indelible mark on the American landscape. The Second Great Awakening ignited Protestant spirits by connecting evangelical Christians in national networks of faith. Social reform spurred members of the middle class to promote national morality and the public good. Not all reform projects were equally successful, however. While the temperance movement made substantial inroads against the excesses of alcohol consumption, the abolitionist movement proved so divisive that it paved the way for sectional crisis. Yet participation in reform movements, regardless of their ultimate success, encouraged many Americans to see themselves in new ways. Black activists became a powerful voice in antislavery societies, for example, developing domestic and transnational connections to pursue the cause of liberty. Middle-class women’s dominant presence in the benevolent empire encouraged them to pursue a full-fledged women’s right movement that has lasted in various forms up through the present day. In their efforts to make the United States a more virtuous and moral nation, nineteenth-century reform activists developed cultural and institutional foundations for social change that have continued to reverberate through the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

到1861年爆发南北战争时,南北战争前期的复兴和改革运动已经在美国社会上留下了不可磨灭的印记。第二次伟大复兴通过将福音派基督徒联结成全国性的信仰网络,激发了新教徒的精神。社会改革促使中产阶级成员推动国家道德和公共利益。然而,并非所有改革项目都同样成功。尽管禁酒运动在抵制酒精过度消费方面取得了显著进展,但废奴运动的分裂性导致了区域性危机的产生。然而,参与改革运动,无论其最终是否成功,都促使许多美国人以全新的方式看待自己。例如,黑人活动家在废奴社团中成为了强有力的声音,发展了国内和跨国的联系,推动自由事业。中产阶级女性在慈善帝国中的主导地位促使她们追求全面的女性权利运动,这一运动至今仍以不同形式存在。19世纪的改革活动家在努力使美国成为一个更有德行和更具道德的国家时,为社会变革打下了文化和制度基础,这些影响一直延续到20世纪和21世纪。