第十一章 棉花革命

原标题:The Cotton Revolution

Source / 原文:https://www.americanyawp.com/text/11-the-cotton-revolution/

I. Introduction

一、引言

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the southern states experienced extraordinary change that would define the region and its role in American history for decades, even centuries, to come. Between the 1830s and the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, the American South expanded its wealth and population and became an integral part of an increasingly global economy. It did not, as previous generations of histories have told, sit back on its cultural and social traditions and insulate itself from an expanding system of communication, trade, and production that connected Europe and Asia to the Americas. Quite the opposite; the South actively engaged new technologies and trade routes while also seeking to assimilate and upgrade its most “traditional” and culturally ingrained practices—such as slavery and agricultural production—within a modernizing world.

在南北战争爆发前的几十年里,南方各州经历了巨大的变革,这些变化不仅塑造了该地区的特征,还决定了它在美国历史上的角色,并在未来数十年甚至数百年里持续影响着美国的发展。从19世纪30年代到1861年南北战争爆发,美国南方的财富和人口迅速增长,并成为日益全球化经济体系中不可或缺的一部分。与早期一些历史研究所描述的那种固守传统文化和社会习俗、自我封闭于欧洲、亚洲和美洲之间不断扩展的交流、贸易和生产体系之外的形象不同,南方实际上积极拥抱新技术和新贸易路线,同时努力在现代化进程中调整和强化其最“传统”且根深蒂固的制度,例如奴隶制和农业生产,以适应不断变化的世界。

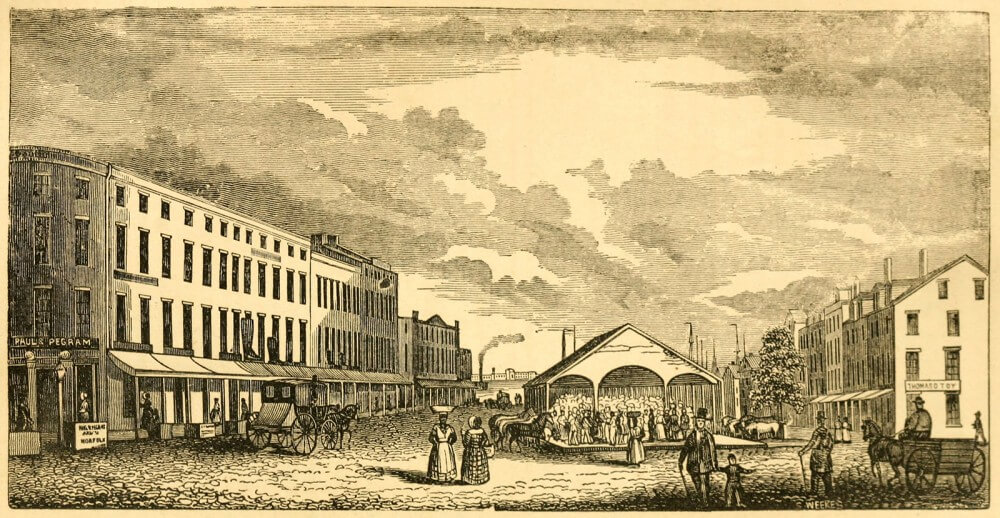

Beginning in the 1830s, merchants from the Northeast, Europe, Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean flocked to southern cities, setting up trading firms, warehouses, ports, and markets. As a result, these cities—Richmond, Charleston, St. Louis, Mobile, Savannah, and New Orleans, to name a few—doubled and even tripled in size and global importance. Populations became more cosmopolitan, more educated, and wealthier. Systems of class—lower-, middle-, and upper-class communities—developed where they had never clearly existed. Ports that had once focused entirely on the importation of enslaved laborers and shipped only regionally became home to daily and weekly shipping lines to New York City, Liverpool, Manchester, Le Havre, and Lisbon. The world was slowly but surely coming closer together, and slavery was right in the middle.

从19世纪30年代开始,来自美国东北部、欧洲、加拿大、墨西哥和加勒比地区的商人纷纷涌入南方各大城市,建立贸易公司、仓库、港口和市场。由此,南方城市——如里士满、查尔斯顿、圣路易斯、莫比尔、萨凡纳和新奥尔良等——规模迅速扩大,有些甚至翻倍甚至三倍增长,在全球经济体系中的地位也大大提升。城市人口变得更加国际化,教育水平提高,财富也在积累。原本不甚分明的社会阶级逐渐成形,底层、中产和上层社会开始出现。曾经只专注于进口奴隶劳工、主要进行区域贸易的港口,如今发展出了往返纽约、利物浦、曼彻斯特、勒阿弗尔和里斯本的日常或每周航运线路。世界正在缓慢却坚定地走向更加紧密的联系,而奴隶制度正处于这一进程的核心位置。

II. The Importance of Cotton

二、棉花的重要性

In November 1785, the Liverpool firm of Peel, Yates & Co. imported the first seven bales of American cotton ever to arrive in Europe. Prior to this unscheduled, and frankly unwanted, delivery, European merchants saw cotton as a product of the colonial Caribbean islands of Barbados, Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), Martinique, Cuba, and Jamaica. The American South, though relatively wide and expansive, was the go-to source for rice and, most importantly, tobacco.

1785年11月,利物浦商行皮尔-耶茨公司(Peel, Yates & Co.)进口了首批抵达欧洲的七包美国产棉花。在此之前,这一非计划内、甚至不受欢迎的货物并未进入欧洲商人的视野。欧洲市场长期以来一直将棉花视为加勒比殖民地的特产,例如巴巴多斯、圣多明各(今海地)、马提尼克、古巴和牙买加。而美国南方虽然幅员辽阔,但主要供应的商品是大米,以及最重要的烟草。

Few knew that the seven bales sitting in Liverpool that winter of 1785 would change the world. But they did. By the early 1800s, the American South had developed a niche in the European market for “luxurious” long-staple cotton grown exclusively on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. But this was only the beginning of a massive flood to come and the foundation of the South’s astronomical rise to global prominence. Before long, botanists, merchants, and planters alike set out to develop strains of cotton seed that would grow farther west on the southern mainland, especially in the new lands opened up by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803—an area that stretched from New Orleans in the South to what is today Minnesota, parts of the Dakotas, and Montana.

1785年冬天,滞留在利物浦的那七包棉花将改变世界,这一点当时鲜有人知。但事实证明,它们确实如此。到了19世纪初,美国南方在欧洲市场上开辟了一个独特的利基市场,专门供应生长于南卡罗来纳、乔治亚和佛罗里达沿海海岛上的“奢华”长绒棉。然而,这只是即将到来的棉花洪流的开端,也是南方迅速崛起成为全球经济重心的基础。不久之后,植物学家、商人和种植园主纷纷投入研究,希望培育出适合南方大陆更西部种植的棉花品种,尤其是在1803年《路易斯安那购地案》开放的新土地上——这一地区从南部的新奥尔良一直延伸到今天的明尼苏达州、达科他州部分地区和蒙大拿州。

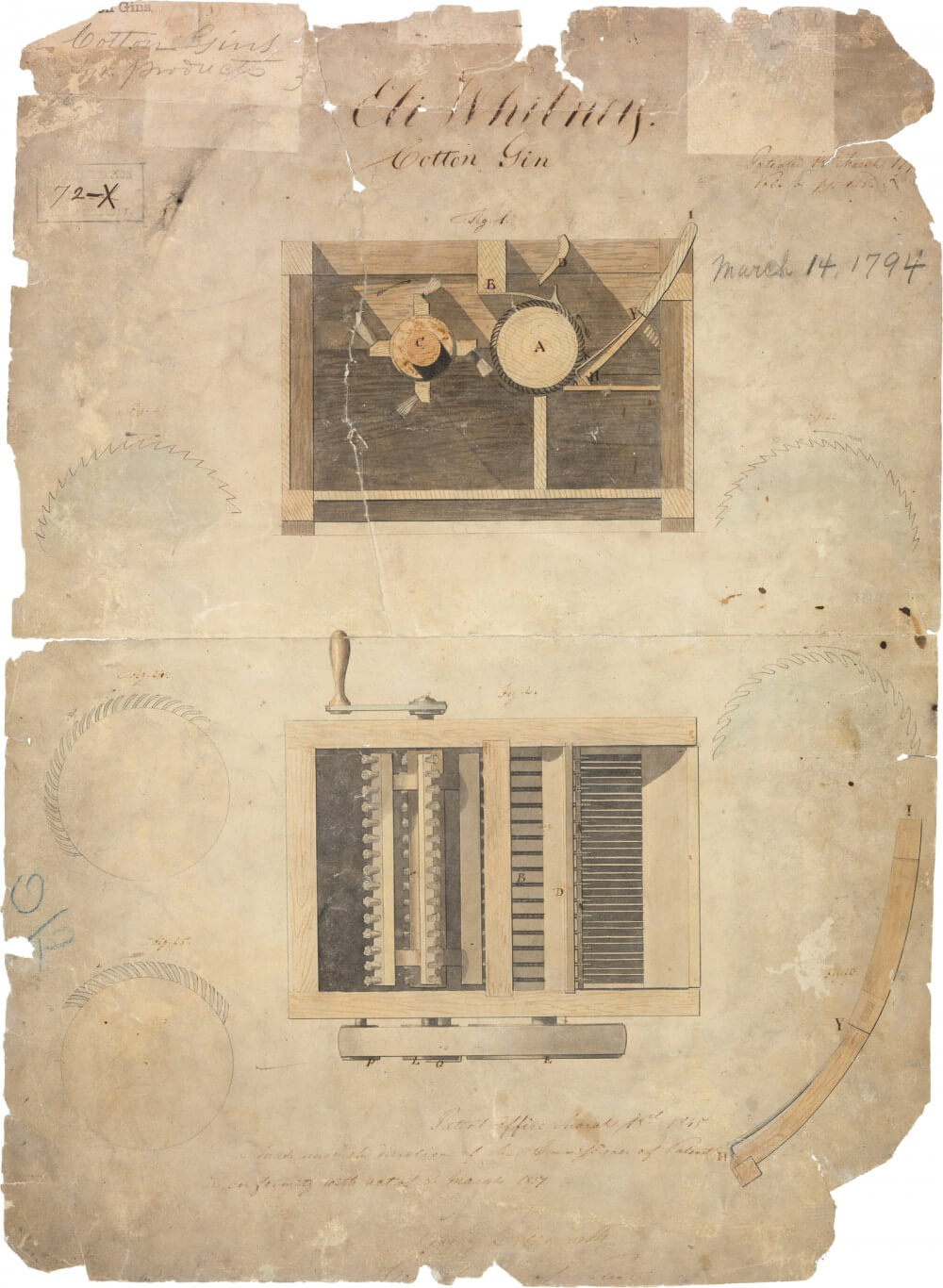

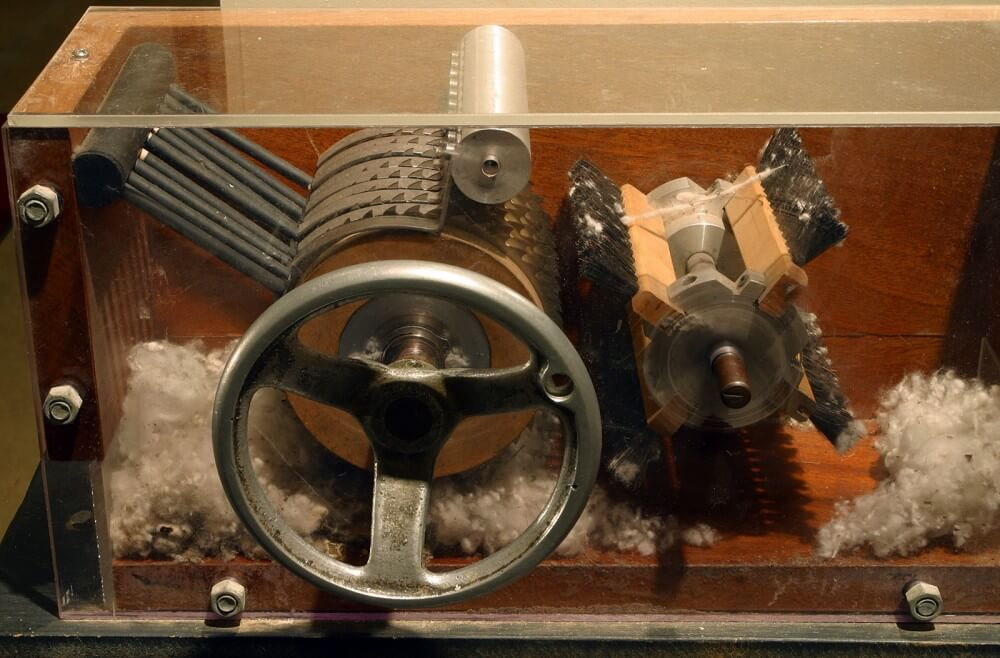

American and global cotton markets changed forever after Rush Nutt of Rodney, Mississippi, developed a hybrid strain of cotton in 1833 that he named Petit Gulf. Petit Gulf, it was said, slid through the cotton gin—a machine developed by Eli Whitney in 1794 for deseeding cotton—more easily than any other strain. It also grew tightly, producing more usable cotton than anyone had imagined to that point. Perhaps most importantly, though, it came up at a time when Native peoples were removed from the Southwest—southern Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and northern Louisiana. After Indian removal, land became readily available for white men with a few dollars and big dreams. Throughout the 1820s and 1830s, the federal government implemented several forced migrations of Native Americans, establishing a system of reservations west of the Mississippi River on which all eastern peoples were required to relocate and settle. This system, enacted through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, allowed the federal government to survey, divide, and auction off millions of acres of land for however much bidders were willing to pay. Suddenly, farmers with dreams of owning a large plantation could purchase dozens, even hundreds, of acres in the fertile Mississippi River Delta for cents on the dollar. Pieces of land that would cost thousands of dollars elsewhere sold in the 1830s for several hundred, at prices as low as 40¢ per acre.

美国和全球棉花市场的格局在1833年发生了永久性的改变,那一年,密西西比州罗德尼(Rodney, Mississippi)的拉什·纳特(Rush Nutt)培育出了一种杂交棉花品种,并将其命名为“小海湾”(Petit Gulf)。据说,小海湾棉通过轧棉机(Eli Whitney于1794年发明的一种去籽机)时,比任何其他品种都更加顺畅。此外,它的株型紧凑,产量比当时人们所能想象的任何品种都要高。然而,也许最重要的是,这一品种的推广正值美国政府对印第安人的迁移政策生效之际——这场迁移涉及南部的佐治亚州、阿拉巴马州、密西西比州以及路易斯安那州北部。在印第安人被迁移之后,土地变得极为廉价,任何手头有点资金、怀揣大梦的白人男子都可以轻松获得土地。 在1820和1830年代,联邦政府多次强制迁移印第安人,将所有东部部落安置到密西西比河以西的保留地。这一体系由《印第安迁移法》(Indian Removal Act of 1830)推动,赋予联邦政府权力,对大片土地进行勘测、划分,并以竞拍方式出售,价高者得。突然间,原本无法负担大种植园的农民,可以用极低的价格购买几十甚至上百英亩的密西西比河三角洲肥沃土地。 在其他地区价值数千美元的土地,在1830年代只需几百美元即可购得,甚至有些土地的价格低至每英亩40美分。

Thousands rushed into the Cotton Belt. Joseph Holt Ingraham, a writer and traveler from Maine, called it a “mania.” William Henry Sparks, a lawyer living in Natchez, Mississippi, remembered it as “a new El Dorado” in which “fortunes were made in a day, without enterprise or work.” The change was astonishing. “Where yesterday the wilderness darkened over the land with her wild forests,” he recalled, “to-day the cotton plantations whitened the earth.” Money flowed from banks, many newly formed, on promises of “other-worldly” profits and overnight returns. Banks in New York City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and even London offered lines of credit to anyone looking to buy land in the Southwest. Some even sent their own agents to purchase cheap land at auction for the express purpose of selling it, sometimes the very next day, at double and triple the original value, a process known as speculation.

成千上万的人涌向“棉花地带”(Cotton Belt)。 来自缅因州的作家和旅行家约瑟夫·霍尔特·英格拉哈姆(Joseph Holt Ingraham)将这一现象称为一种“狂热”(mania)。居住在密西西比州纳奇兹(Natchez, Mississippi)的律师威廉·亨利·斯帕克斯(William Henry Sparks)将其比作一个“新的黄金国”(El Dorado),在那里“财富可以在一天之内凭空而来,无需任何商业智慧或劳动。”这种变化令人震惊。 斯帕克斯回忆道:“昨日,这片土地还是被原始森林所笼罩的荒野;今日,棉田已将大地染成一片雪白。” 资本从银行源源不断地流出,其中许多银行刚刚成立,人们凭借着对“超乎想象的”利润和一夜暴富的承诺,纷纷借贷投资。纽约、巴尔的摩、费城,甚至伦敦的银行 都愿意为任何想在美国西南部购买土地的人提供信贷。一些银行甚至派出自己的代理人,专门在拍卖会上以低价购入土地,然后有时第二天就以两倍、三倍的价格转手卖出。这种行为被称为“土地投机”(speculation)。

The explosion of available land in the fertile Cotton Belt brought new life to the South. By the end of the 1830s, Petit Gulf cotton had been perfected, distributed, and planted throughout the region. Advances in steam power and water travel revolutionized southern farmers’ and planters’ ability to deseed and bundle their products and move them to ports popping up along the Atlantic seaboard. Indeed, by the end of the 1830s, cotton had become the primary crop not only of the southwestern states but of the entire nation.

肥沃的“棉花地带”土地大量开放,为美国南方注入了新的活力。 到1830年代末,小海湾棉(Petit Gulf cotton)的种植技术已趋于完善,并在整个地区得到推广和种植。蒸汽动力和水上交通的进步彻底改变了南方农民和种植园主的生产与运输方式。 这些技术革新使他们能够更高效地去除棉籽、打包棉花,并将其迅速运往大西洋沿岸的新兴港口。到1830年代末,棉花不仅成为美国西南部各州的主要作物,甚至成为整个国家的经济支柱。

The numbers were staggering. In 1793, just a few years after the first, albeit unintentional, shipment of American cotton to Europe, the South produced around five million pounds of cotton, again almost exclusively the product of South Carolina’s Sea Islands. Seven years later, in 1800, South Carolina remained the primary cotton producer in the South, sending 6.5 million pounds of the luxurious long-staple blend to markets in Charleston, Liverpool, London, and New York. But as the tighter, more abundant, and vibrant Petit Gulf strain moved west with the dreamers, schemers, and speculators, the American South quickly became the world’s leading cotton producer. By 1835, the five main cotton-growing states—South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—produced more than five hundred million pounds of Petit Gulf for a global market stretching from New Orleans to New York and to London, Liverpool, Paris and beyond. That five hundred million pounds of cotton made up nearly 55 percent of the entire United States export market, a trend that continued nearly every year until the outbreak of the Civil War. Indeed, the two billion pounds of cotton produced in 1860 alone amounted to more than 60 percent of the United States’ total exports for that year.

棉花产量的增长速度令人震惊。 1793年,在美国棉花首次(尽管是无意的)出口到欧洲后不久,美国南方的棉花产量约为500万磅,这些棉花几乎全部产自南卡罗来纳州的海岛地区。七年后的1800年,南卡罗来纳仍是南方主要的棉花生产地,向查尔斯顿、利物浦、伦敦和纽约等市场输送了650万磅优质的长绒棉。 然而,随着产量更高、适应性更强的小海湾棉(Petit Gulf)向西扩展,南方的棉花产业迅速崛起。到1835年,南卡罗来纳、佐治亚、阿拉巴马、密西西比和路易斯安那这五个主要棉花种植州生产了超过5亿磅的小海湾棉,供应全球市场。 这些棉花经由新奥尔良运往纽约、伦敦、利物浦、巴黎及其他国际市场。这一年,棉花占据了美国出口总额的近55%,这一趋势几乎持续至南北战争爆发。 仅1860年一年,美国南方生产的棉花就达到了惊人的20亿磅,占该年美国出口总额的60%以上。

The astronomical rise of American cotton production came at the cost of the South’s first staple crop—tobacco. Perfected in Virginia but grown and sold in nearly every southern territory and state, tobacco served as the South’s main economic commodity for more than a century. But tobacco was a rough crop. It treated the land poorly, draining the soil of nutrients. Tobacco fields did not last forever. In fact, fields rarely survived more than four or five cycles of growth, which left them dried and barren, incapable of growing much more than patches of grass. Of course, tobacco is, and was, an addictive substance, but because of its declining yields, farmers had to move around, purchasing new lands, developing new methods of production, and even creating new fields through deforestation and westward expansion. Tobacco, then, was expensive to produce—and not only because of the ubiquitous use of slave labor. It required massive, temporary fields, large numbers of laborers, and constant movement.

美国棉花产业的飞速崛起,以南方的第一大经济作物——烟草——的衰落为代价。烟草最早在弗吉尼亚得到优化,随后几乎在所有南方领土和州份种植,并作为南方经济的主要支柱长达一个多世纪。然而,烟草是一种对土地破坏性极大的作物,会迅速消耗土壤养分,使土地贫瘠。烟草种植地的寿命极短,通常只能维持四到五轮种植周期,之后便会干枯荒废,几乎无法再种植除杂草以外的任何作物。 尽管烟草是一种成瘾性极强的商品,市场需求稳定,但由于产量不断下降,农民不得不四处迁移,购买新土地、开发新的种植方法,甚至通过砍伐森林和西进扩张来开辟新的种植地。因此,烟草的生产成本极高,且不仅仅因为它依赖大量奴隶劳动。 它需要大面积的临时性种植地、大量劳动力,以及不断的迁移,使其成为一种昂贵且难以持续的经济作物。

Cotton was different, and it arrived at a time best suited for its success. Petit Gulf cotton, in particular, grew relatively quickly on cheap, widely available land. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1794, and the emergence of steam power three decades later, cotton became the common person’s commodity, the product with which the United States could expand westward, producing and reproducing Thomas Jefferson’s vision of an idyllic republic of small farmers—a nation in control of its land, reaping the benefits of honest, free, and self-reliant work, a nation of families and farmers, expansion and settlement. But this all came at a violent cost. With the democratization of land ownership through Indian removal, federal auctions, readily available credit, and the seemingly universal dream of cotton’s immediate profit, one of the South’s lasting traditions became normalized and engrained. And by the 1860s, that very tradition, seen as the backbone of southern society and culture, would split the nation in two. The heyday of American slavery had arrived.

棉花则截然不同,它的崛起恰逢最佳时机。尤其是小海湾棉(Petit Gulf cotton),它不仅生长周期较短,而且适应于当时廉价且广袤的新土地。1794年轧棉机的发明,再加上三十年后蒸汽动力的普及,使棉花成为一种“平民商品”——它成了推动美国西进扩张的重要经济支柱,同时也成为了托马斯·杰斐逊所描绘的“小农共和国”理想的象征:一个土地在民、依靠诚实劳动和自给自足维持生计的国家,一个由家庭和农民组成、不断扩张和定居的国家。然而,这一切都建立在暴力之上。随着印第安人被强制迁移、联邦政府拍卖土地、信贷广泛提供,以及人们普遍憧憬棉花带来的快速暴利,南方的“传统”——即奴隶制度——被进一步强化,并深深嵌入社会结构之中。到了19世纪60年代,这一被视为南方社会和文化支柱的制度,最终将整个国家撕裂。美国奴隶制的黄金时代到来了。

III. Cotton and Slavery

三、棉花与奴隶制

The rise of cotton and the resulting upsurge in the United States’ global position wed the South to slavery. Without slavery there could be no Cotton Kingdom, no massive production of raw materials stretching across thousands of acres worth millions of dollars. Indeed, cotton grew alongside slavery. The two moved hand-in-hand. The existence of slavery and its importance to the southern economy became the defining factor in what would be known as the Slave South. Although slavery arrived in the Americas long before cotton became a profitable commodity, the use and purchase of enslaved laborers, the moralistic and economic justifications for the continuation of slavery, and even the urgency to protect the practice from extinction before the Civil War all received new life from the rise of cotton and the economic, social, and cultural growth spurt that accompanied its success.

棉花的崛起及其带来的美国全球地位的上升,使南方与奴隶制紧密相连。没有奴隶制,就没有棉花王国,也没有跨越成千上万英亩、价值数百万美元的大规模原料生产。 事实上,棉花与奴隶制是并行发展的,两者相辅相成。奴隶制的存在及其对南方经济的重要性成为了“奴隶南方”这一概念的定义性因素。虽然奴隶制早于棉花成为有利可图的商品便已进入美洲,但奴隶劳动的使用与购买、奴隶制继续存在的道德和经济理由,乃至在南北战争前对保护奴隶制的迫切需求,都因棉花的崛起及随之而来的经济、社会和文化的增长而获得了新的生命力。

Slavery had existed in the South since at least 1619, when a group of Dutch traders arrived at Jamestown with twenty Africans. Although these Africans remained under the ambiguous legal status of “unfree” rather than being actually enslaved, their arrival set in motion a practice that would stretch across the entire continent over the next two centuries. Slavery was everywhere by the time the American Revolution created the United States, although northern states began a process of gradually abolishing the practice soon thereafter. In the more rural, agrarian South, slavery became a way of life, especially as farmers expanded their lands, planted more crops, and entered the international trade market. By 1790, two years after the ratification of the Constitution, 654,121 enslaved people lived in the South—then just Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and the Southwest Territory (now Tennessee). Just twenty years later, in 1810, that number had increased to more than 1.1 million individuals in bondage.

奴隶制自1619年起在南方存在,当时一群荷兰商人将20名非洲人带到詹姆斯敦。虽然这些非洲人以“非自由人”的模糊法律身份存在,而非被正式奴役,但他们的到来开启了一项实践,这种做法在接下来的两个世纪里蔓延至整个大陆。到了美国革命时,奴隶制在南方几乎无处不在,尽管北方各州随即开始逐步废除这一制度。在更为乡村化、农业化的南方,奴隶制成为了一种生活方式,尤其是随着农民扩展土地、种植更多作物,并进入国际贸易市场。到1790年,即宪法通过后的两年,南方有654,121名奴隶,涵盖当时的马里兰、弗吉尼亚、北卡罗来纳、南卡罗来纳、乔治亚州和西南领土(现为田纳西州)。仅仅20年后的1810年,这一数字就增加到超过110万。

The massive change in the South’s enslaved population between 1790 and 1810 makes historical sense. During that time, the South advanced from a region of four states and one rather small territory to a region of six states (Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee) and three rather large territories (Mississippi, Louisiana, and Orleans). The free population of the South also nearly doubled over that period—from around 1.3 million in 1790 to more than 2.3 million in 1810. The enslaved population of the South did not increase at any rapid rate over the next two decades, until the cotton boom took hold in the mid-1830s. Indeed, following the constitutional ban on the international slave trade in 1808, the number of enslaved people in the South increased by just 750,000 in twenty years.

1790年到1810年之间,南方奴隶人口的巨大变化具有历史意义。在这段时间里,南方从一个由四个州和一个相对较小的领土组成的地区,发展成了由六个州(弗吉尼亚、北卡、南卡、乔治亚、肯塔基、田纳西)和三个相对较大的领土(密西西比、路易斯安那和新奥尔良)组成的地区。与此同时,南方的自由人口在这一时期几乎翻倍,从1790年的约130万增加到1810年的230多万。在接下来的二十年里,直到1830年代中期棉花产业的繁荣,南方的奴隶人口并未迅速增加。事实上,在1808年宪法禁止国际奴隶贸易之后,南方奴隶人口在接下来的二十年内仅增加了大约75万人。

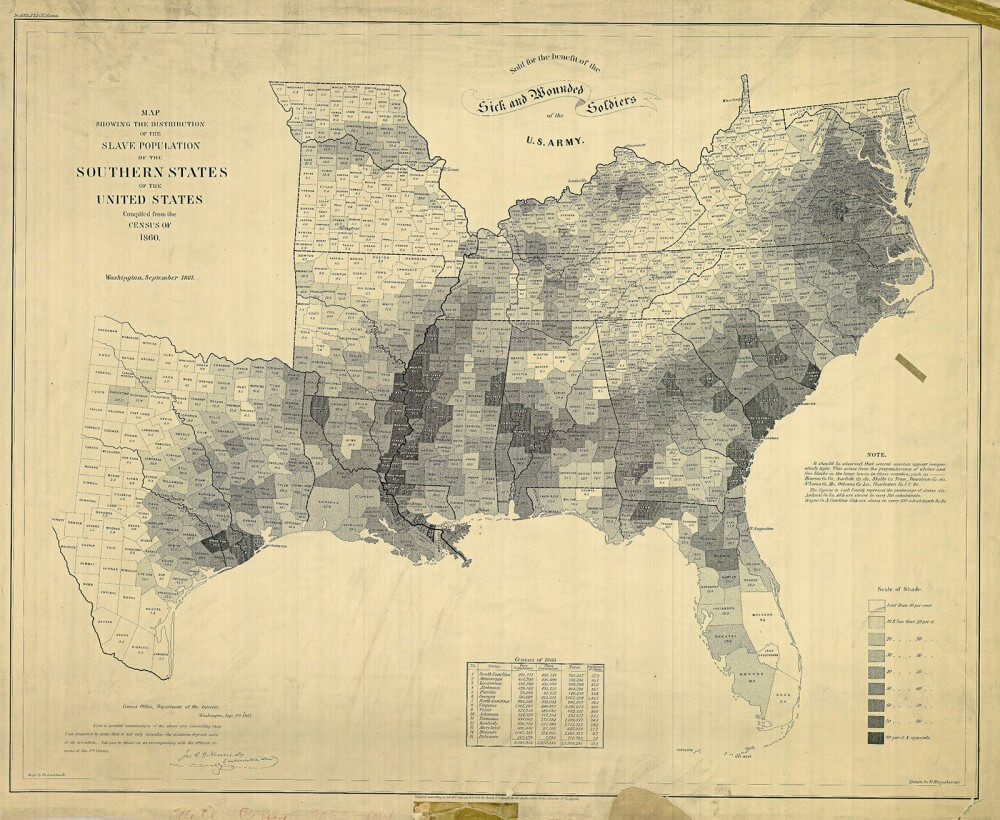

But then cotton came, and grew, and changed everything. Over the course of the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, slavery became so endemic to the Cotton Belt that travelers, writers, and statisticians began referring to the area as the Black Belt, not only to describe the color of the rich land but also to describe the skin color of those forced to work its fields, line its docks, and move its products.

但是随后棉花产业的兴起彻底改变了一切。在1830年代、1840年代和1850年代的过程中,奴隶制在棉花带变得如此根深蒂固,以至于旅行者、作家和统计学家开始称该地区为“黑带”,这不仅是为了描述那片富饶土地的颜色,也为了描述那些被迫在其田野、码头上劳动、并运输其产品的人的肤色。

Perhaps the most important aspect of southern slavery during this so-called Cotton Revolution was the value placed on both the work and the bodies of the enslaved themselves. Once the fever of the initial land rush subsided, land values became more static and credit less free-flowing. For Mississippi land that in 1835 cost no more than $600, a farmer or investor would have to shell out more than $3,000 in 1850. By 1860, that same land, depending on its record of production and location, could cost as much as $100,000. In many cases, cotton growers, especially planters with large lots and enslaved workforces, put up enslaved laborers as collateral for funds dedicated to buying more land. If that land, for one reason or another, be it weevils, a late freeze, or a simple lack of nutrients, did not produce a viable crop within a year, the planter would lose not only the new land but also the enslaved laborers he or she put up as a guarantee of payment.

在这场所谓的棉花革命期间,南方奴隶制最重要的方面之一是对奴隶劳动和奴隶身体的价值的重视。一旦最初的土地抢购热潮平息,土地的价值变得更加稳定,信贷也不再那么容易获取。例如,在1835年,密西西比州的土地价格不过600美元,但到了1850年,农民或投资者若要购买同样的土地,必须支付超过3000美元。到了1860年,根据土地的生产记录和位置,这块土地的价格可能高达10万美元。在许多情况下,棉花种植者,尤其是拥有大块土地和大量奴隶劳动力的种植园主,会将奴隶作为抵押物来获取用于购买更多土地的资金。如果这些土地由于某些原因(如虫害、晚霜或土壤贫瘠)未能在一年内收获可行的作物,种植园主不仅会失去新土地,还会失去他或她作为付款担保的奴隶劳动力。

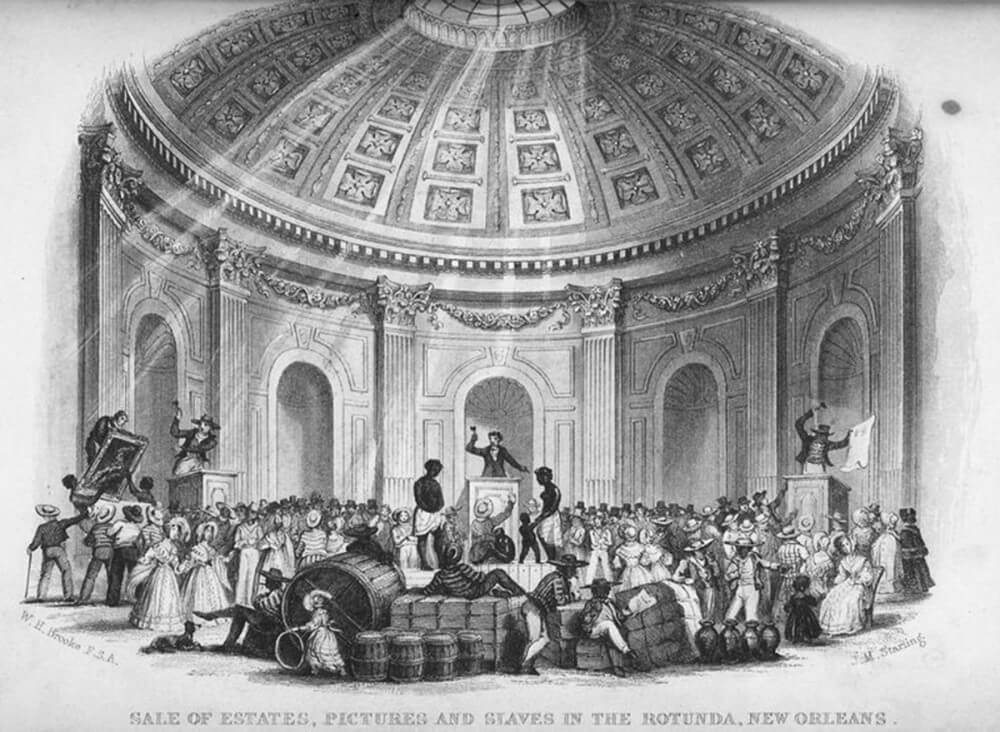

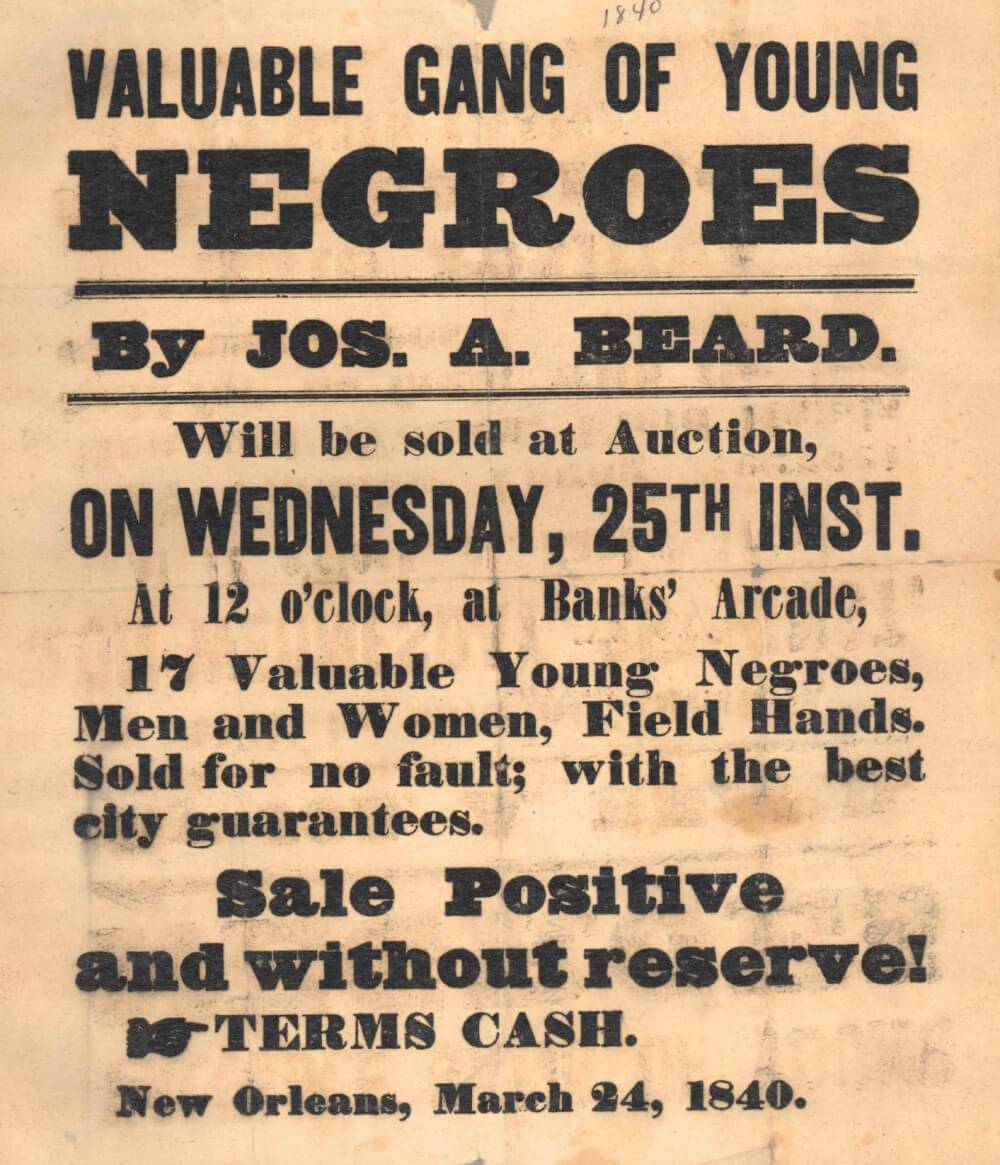

So much went into the production of cotton, the expansion of land, and the maintenance of enslaved workforces that by the 1850s, nearly every ounce of credit offered by southern, and even northern, banks dealt directly with some aspect of the cotton market. Millions of dollars changed hands. Enslaved people, the literal and figurative backbone of the southern cotton economy, served as the highest and most important expense for any successful cotton grower. Prices for enslaved laborers varied drastically, depending on skin color, sex, age, and location, both of purchase and birth. In Virginia in the 1820s, for example, a single enslaved woman of childbearing age sold for an average of $300; an unskilled man above age eighteen sold for around $450; and boys and girls below age thirteen sold for between $100 and $150.

棉花的生产、土地的扩展以及奴隶劳动力的维持投入了如此多的资源,以至于到了1850年代,几乎每一分由南方甚至北方银行提供的信贷都与棉花市场的某个方面直接相关。数百万美元在交易中流动。奴隶,作为南方棉花经济的字面和象征性支柱,成为任何成功棉花种植者的最高且最重要的开支。奴隶的价格差异巨大,取决于肤色、性别、年龄以及购买和出生的地点。例如,在1820年代的弗吉尼亚州,一名处于育龄的女性奴隶的售价平均为300美元;一名18岁以上的无技能男性奴隶售价约为450美元;而13岁以下的男孩和女孩售价在100到150美元之间。

By the 1840s and into the 1850s, prices had nearly doubled—a result of both standard inflation and the increasing importance of enslaved laborers in the cotton market. In 1845, “plow boys” under age eighteen sold for more than $600 in some areas, measured at “five or six dollars per pound.” “Prime field hands,” as they were called by merchants and traders, averaged $1,600 at market by 1850, a figure that fell in line with the rising prices of the cotton they picked. For example, when cotton sat at 7¢ per pound in 1838, the average “field hand” cost around $700. As the price of cotton increased to 9¢, 10¢, then 11¢ per pound over the next ten years, the average cost of an enslaved male laborer likewise rose to $775, $900, and then more than $1,600.

到1840年代和1850年代初期,奴隶的价格几乎翻了一番,这既是由于通货膨胀的普遍影响,也与奴隶劳动力在棉花市场中日益重要的地位密切相关。到1845年,“耕地仔”(plow boys)——即18岁以下的男奴——在某些地区的售价超过600美元,相当于“每磅五到六美元”。而被商人和贸易商称为“精壮田间劳力”的“成熟劳工”到1850年平均售价达到1600美元,这一价格与他们所采摘棉花的价格上涨相符。例如,当1838年棉花价格为每磅7美分时,普通“田间劳工”的平均价格约为700美元。随着棉花价格在接下来的十年里涨到每磅9美分、10美分,甚至11美分,奴隶男性劳动力的平均价格也相应地从775美元上涨至900美元,最终超过1600美元。

The key is that cotton and enslaved labor helped define each other, at least in the cotton South. By the 1850s, slavery and cotton had become so intertwined that the very idea of change—be it crop diversity, antislavery ideologies, economic diversification, or the increasingly staggering cost of purchasing and maintaining enslaved laborers—became anathema to the southern economic and cultural identity. Cotton had become the foundation of the southern economy. Indeed, it was the only major product, besides perhaps sugarcane in Louisiana, that the South could effectively market internationally. As a result, southern planters, politicians, merchants, and traders became more and more dedicated—some would say “obsessed”—to the means of its production: slavery. In 1834, Joseph Ingraham wrote that “to sell cotton in order to buy negroes—to make more cotton to buy more negroes, ‘ad infinitum,’ is the aim and direct tendency of all the operations of the thorough going cotton planter; his whole soul is wrapped up in the pursuit.” Twenty-three years later, such pursuit had taken a seemingly religious character, as James Stirling, an Englishman traveling through the South, observed, “[slaves] and cotton—cotton and [slaves]; these are the law and the prophets to the men of the South.”

关键在于,棉花和奴隶劳动力在棉花种植南方互相塑造并定义了彼此。到了1850年代,奴隶制与棉花已经紧密交织在一起,以至于改变的观念——无论是作物多样化、反奴隶制思想、经济多元化,还是越来越高昂的购买和维持奴隶劳动力的成本——都成为南方经济与文化认同的禁忌。棉花已经成为南方经济的基础。事实上,除了路易斯安那州的甘蔗外,棉花几乎是南方唯一能够有效在国际市场上推广的主要产品。因此,南方的种植园主、政治家、商人和贸易商变得越来越执着——有些人甚至说是“痴迷”——于棉花生产的手段:奴隶制。1834年,约瑟夫·英格拉汉姆写道:“为了买奴隶而卖棉花——为了种更多棉花以购买更多奴隶,这就是所有彻底的棉花种植者操作的目的和直接趋势;他的整个灵魂都沉浸在这一追求中。”二十三年后,这种追求似乎已经带上了宗教色彩,正如英国人詹姆斯·斯特林在旅行中观察到的:“(奴隶)和棉花——棉花和(奴隶);这些是南方人的律法和先知。”

The Cotton Revolution was a time of capitalism, panic, stress, and competition. Planters expanded their lands, purchased enslaved laborers, extended lines of credit, and went into massive amounts of debt because they were constantly working against the next guy, the newcomer, the social mover, the speculator, the trader. A single bad crop could cost even the most wealthy planter his or her entire life, along with those of his or her enslaved laborers and their families. Although the cotton market was large and profitable, it was also fickle, risky, and cost intensive. The more wealth one gained, the more land one needed to procure, which led to more enslaved laborers, more credit, and more mouths to feed. The decades before the Civil War in the South, then, were not times of slow, simple tradition. They were times of high competition, high risk, and high reward, no matter where one stood in the social hierarchy. But the risk was not always economic.

棉花革命是一个充满资本主义、恐慌、压力和竞争的时代。种植园主扩展土地,购买奴隶劳动力,延长信用期限,陷入巨额债务,因为他们不断与竞争对手较量,面对新来者、社会活动家、投机者和商人。一次糟糕的收成可能让即便是最富有的种植园主也失去一生的积蓄,甚至连同他们的奴隶劳工及其家庭一起失去一切。尽管棉花市场庞大且利润丰厚,但它也是反复无常、充满风险和成本高昂的。财富越多,所需的土地就越多,进而导致更多的奴隶劳动力、更大的信贷需求和更多的食物需求。因此,南方内战前的几十年并非缓慢、简单的传统时期,而是充满了激烈竞争、高风险和高回报的时光,不论身处社会阶层的哪个位置。但这种风险并不总是经济上的。

The most tragic, indeed horrifying, aspect of slavery was its inhumanity. All enslaved people had memories, emotions, experiences, and thoughts. They saw their experiences in full color, felt the pain of the lash, the heat of the sun, and the heartbreak of loss, whether through death, betrayal, or sale. Communities developed on a shared sense of suffering, common work, and even family ties. Enslaved people communicated in the slave markets of the urban South and worked together to help their families, ease their loads, or simply frustrate their enslavers. Simple actions of resistance, such as breaking a hoe, running a wagon off the road, causing a delay in production due to injury, running away, or even pregnancy provided a language shared by nearly all enslaved laborers, a sense of unity that remained unsaid but was acted out daily.

奴隶制最悲惨、甚至最可怕的一面是它的非人性。所有奴隶都有记忆、情感、经历和思想。他们清晰地记得自己的经历,感受过鞭笞的痛苦、烈日的炙烤,以及失去亲人的心碎——无论是通过死亡、背叛还是被买卖。奴隶们在共同的苦难、共同的劳动,甚至是家庭纽带中形成了社区。奴隶们在南方城市的奴隶市场中交流合作,帮助家庭、减轻负担,或仅仅是为了挫败奴隶主的意图。简单的反抗行为,如弄坏一把锄头、把马车驶出道路、因受伤造成生产延误、逃跑,甚至怀孕,都成为了几乎所有奴隶工人共享的“语言”,这是一种未曾言明但却在日常生活中被实践的团结感。

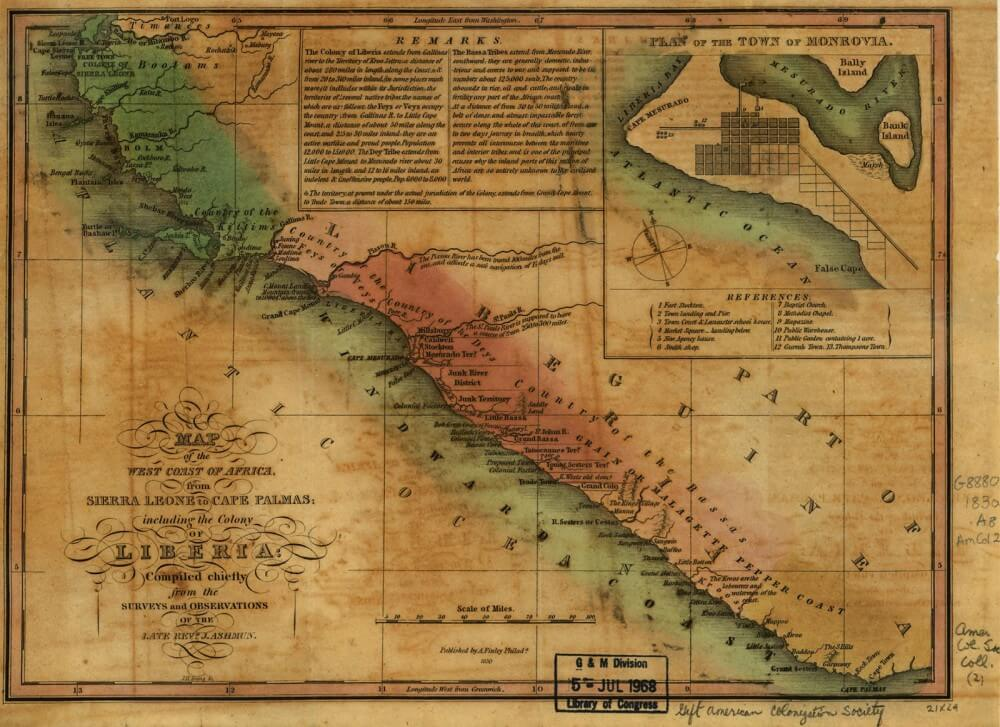

Beyond the basic and confounding horror of it all, the problem of slavery in the cotton South was twofold. First and most immediate was the fear and risk of rebellion. With nearly four million individual enslaved people residing in the South in 1860, and nearly 2.5 million living in the Cotton Belt alone, the system of communication, resistance, and potential violence among enslaved people did not escape the minds of enslavers across the region and the nation as a whole. As early as 1785, Thomas Jefferson wrote in his Notes on the State of Virginia that the enslaved should be freed, but then they should be colonized to another country, where they could become an “independent people.” White people’s prejudices, and Black people’s “recollections . . . of the injuries they have sustained” under slavery, would keep the two races from successfully living together in America. If freed people were not colonized, eventually there would be “convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race.”

除了基本的、令人困惑的恐怖之外,南方棉花种植区的奴隶制问题还涉及两个方面。首先,也是最直接的问题,是对叛乱的恐惧和风险。1860年,南方有接近400万被奴役人口,其中仅棉花带就有近250万。奴隶之间的沟通、反抗和潜在暴力行为并未逃脱奴隶主的视线,奴隶主们在整个地区甚至全国范围内都在关注这一点。早在1785年,托马斯·杰斐逊就在《弗吉尼亚州笔记》一书中写道,奴隶应当被解放,但解放后的奴隶被殖民到其他国家,在那里他们可以成为“独立的民族”。他认为,白人的偏见和黑人“对在奴隶制下所遭受伤害的记忆”将使得两种族在美国无法和睦相处。如果被解放的奴隶没有被送往殖民地,最终将会发生“除非某一族群被消灭,否则可能永远不会结束的动乱”。

Southern writers, planters, farmers, merchants, and politicians expressed the same fears more than a half century later. “The South cannot recede,” declared an anonymous writer in an 1852 issue of the New Orleans–based De Bow’s Review. “She must fight for her slaves or against them. Even cowardice would not save her.” To many enslaveers in the South, slavery was the saving grace of not only their own economic stability but also the maintenance of peace and security in everyday life. Much of pro-slavery ideology rested on the notion that slavery provided a sense of order, duty, and legitimacy to the lives of individual enslaved people, feelings that Africans and African Americans, it was said, could not otherwise experience. Without slavery, many thought, “blacks” (the word most often used for “slaves” in regular conversation) would become violent, aimless, and uncontrollable.

南方的作家、种植园主、农民、商人和政治家们在半个多世纪后仍然表达了相同的恐惧。1852年,《德博评论》新奥尔良版的一位匿名作者宣称:“南方不能退缩,她必须为奴隶而战,或是与奴隶作对。即使是懦弱也无法拯救她。”对于南方许多奴隶主来说,奴隶制不仅是他们自身经济稳定的保障,也是维持日常生活秩序与安全的基础。亲奴隶制的思想基础之一就是奴隶制为奴隶的生活提供了一种秩序、责任感和合法性,而这种感受是他们认为非洲人和非洲裔美国人无法在没有奴隶制的情况下体验到的。许多人认为,没有奴隶制,所谓的“黑人”(在日常交流中,通常用这个词指代奴隶)会变得暴力、无目标、且无法控制。

Some commentators recognized the problem in the 1850s as the internal slave trade, the legal trade of enslaved laborers between states, along rivers, and along the Atlantic coastline. The internal trade picked up in the decade before the Civil War. The problem was rather simple. The more enslaved laborers one owned, the more money it cost to maintain them and to extract product from their work. As planters and cotton growers expanded their lands and purchased more enslaved laborers, their expectations increased.

一些评论者在1850年代意识到问题所在,那就是国内奴隶贸易,即奴隶在各州之间、沿河流以及大西洋沿岸的合法买卖。国内奴隶贸易在内战前的十年间加速发展。问题相当简单。一个人拥有的奴隶越多,维持他们的生活以及从他们的劳动中提取产品的成本就越高。随着种植园主和棉花种植者扩展土地并购买更多的奴隶,他们的预期也随之增加。

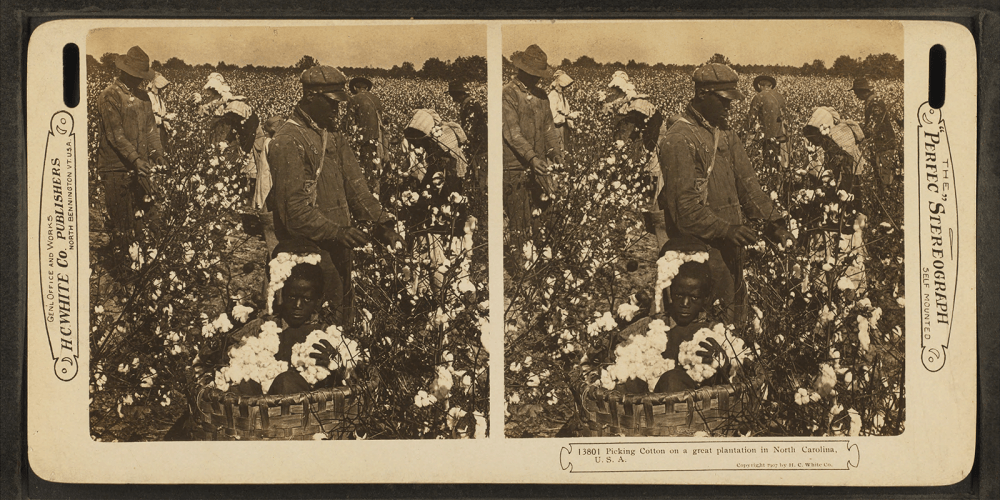

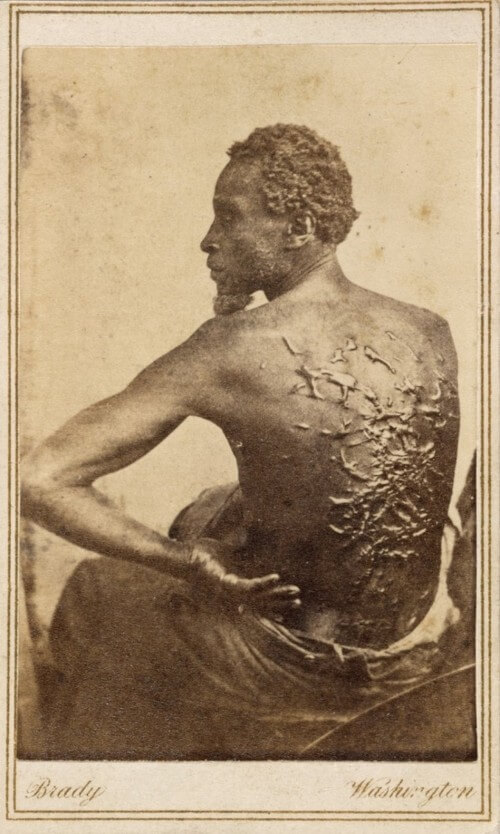

And productivity, in large part, did increase. But it came on the backs of enslaved laborers with heavier workloads, longer hours, and more intense punishments. “The great limitation to production is labor,” wrote one commentator in the American Cotton Planter in 1853. And many planters recognized this limitation and worked night and day, sometimes literally, to find the furthest extent of that limit. According to some contemporary accounts, by the mid-1850s, the expected production of an individual enslaved person in Mississippi’s Cotton Belt had increased from between four and five bales (weighing about 500 pounds each) per day to between eight and ten bales per day, on average. Other, perhaps more reliable sources, such as the account book of Buena Vista Plantation in Tensas Parish, Louisiana, list average daily production at between 300 and 500 pounds “per hand,” with weekly averages ranging from 1,700 to 2,100 pounds “per hand.” Cotton production “per hand” increased by 600 percent in Mississippi between 1820 and 1860. Each slave, then, was working longer, harder hours to keep up with his or her enslavers expected yield.

生产力在很大程度上确实提高了。但这一切都是建立在奴隶劳动力更重的工作量、更长的工作时间和更严厉的惩罚之上。1853年,一位评论员在《美国棉花种植者》上写道:“生产的最大限制是劳动力。”许多种植园主认识到这一限制,并昼夜工作,有时是字面意思上的“不分昼夜”,去探究这一限制的极限。根据一些当时的记载,到1850年代中期,密西西比棉花带一个奴隶的预期生产量已经从每天四到五包(每包约500磅)增加到每天平均八到十包。其他一些或许更可靠的来源,比如路易斯安那州坦萨斯教区布埃纳·维斯塔种植园的账簿,列出了“每人”每日平均产量为300到500磅,每周平均产量则在1,700到2,100磅之间。根据这些数据,密西西比州每个奴隶的棉花生产量在1820年到1860年之间增加了600%。因此,每个奴隶都在为赶上奴隶主的预期产量而加倍努力,工作时间更长,工作强度更大。

Here was capitalism with its most colonial, violent, and exploitative face. Humanity became a commodity used and worked to produce profit for a select group of investors, regardless of its shortfalls, dangers, and immoralities. But slavery, profit, and cotton did not exist only in the rural South. The Cotton Revolution sparked the growth of an urban South, cities that served as southern hubs of a global market, conduits through which the work of enslaved people and the profits of planters met and funded a wider world.

这就是资本主义最具殖民性、暴力性和剥削性的面貌。人类成为了一种商品,被利用和剥削,来为一小部分投资者创造利润,不管其中的缺陷、危险和不道德性。可是,奴隶制、利润和棉花并非仅存在于乡村南方。棉花革命催生了一个城市化的南方,那些城市成为了全球市场的南方枢纽,奴隶劳动的成果和种植园主的利润通过这些城市与更广阔的世界连接,资助着更广泛的世界经济。

IV. The South and the City

四、南方与城市

Much of the story of slavery and cotton lies in the rural areas where cotton actually grew. Enslaved laborers worked in the fields, and planters and farmers held reign over their plantations and farms. But the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s saw an extraordinary spike in urban growth across the South. For nearly a half century after the Revolution, the South existed as a series of plantations, county seats, and small towns, some connected by roads, others connected only by rivers, streams, and lakes. Cities certainly existed, but they served more as local ports than as regional, or national, commercial hubs. For example, New Orleans, then the capital of Louisiana, which entered the union in 1812, was home to just over 27,000 people in 1820; and even with such a seemingly small population, it was the second-largest city in the South—Baltimore had more than 62,000 people in 1820. Given the standard nineteenth-century measurement of an urban space (2,500+ people), the South had just ten in that year, one of which—Mobile, Alabama—contained only 2,672 individuals, nearly half of whom were enslaved.

奴隶制和棉花的故事大部分发生在实际种植棉花的乡村地区。奴隶在田间劳作,种植园主和农场主统治着他们的种植园和农场。但在1830年代、1840年代和1850年代,南方的城市化进程出现了极为显著的增长。在独立战争后的近半个世纪里,南方一直是由一系列种植园、县城和小镇组成的,有些通过道路连接,另一些则仅通过河流、溪流和湖泊相连。尽管当时确实存在一些城市,但它们更多是作为地方港口而非区域性或全国性的商业中心。比如,新奥尔良,当时是路易斯安那州的首府,路易斯安那州在1812年加入联邦,1820年时人口略超过27,000人;尽管如此,这个看似较小的城市仍是南方第二大城市——而巴尔的摩在1820年时有超过62,000人。根据19世纪常用的城市规模标准(人口2,500人以上),当时南方只有十个城市,其中之一——阿拉巴马州的莫比尔——人口仅为2,672人,几乎一半是奴隶。

As late as the 1820s, southern life was predicated on a rural lifestyle—farming, laboring, acquiring land and enslaved laborers, and producing whatever that land and those enslaved laborers could produce. The market, often located in the nearest town or city, rarely stretched beyond state lines. Even in places like New Orleans, Charleston, and Norfolk, Virginia, which had active ports as early as the 1790s, shipments rarely, with some notable exceptions, left American waters or traveled farther than the closest port down the coast. In the first decades of the nineteenth century, American involvement in international trade was largely confined to ports in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and sometimes Baltimore—which loosely falls under the demographic category of the South. Imports dwarfed exports. In 1807, U.S. imports outnumbered exports by nearly $100 million, and even as the Napoleonic Wars broke out in Europe, causing a drastic decrease in European production and trade, the United States still took in almost $50 million more than it sent out.

直到1820年代,南方的生活方式仍然依赖于农村生活——耕作、劳作、获取土地和奴隶劳动力,并生产这些土地和奴隶劳动力所能生产的一切。市场通常位于最近的城镇或城市,很少超出州界。即便是在像新奥尔良、查尔斯顿和弗吉尼亚州诺福克这样的地方,这些地方早在1790年代就拥有活跃的港口,货物运输也很少离开美国水域,或者远行到沿海最接近的港口。在十九世纪的最初几十年,美国的国际贸易基本上局限于纽约、波士顿、费城和有时巴尔的摩等港口,而这些地方大致上都属于南方地区。进口远远超过了出口。1807年,美国的进口超过出口近1亿美元,即使在拿破仑战争爆发后,导致欧洲生产和贸易急剧下降,美国依然进口了比出口多近5000万美元的商品。

Cotton changed much of this, at least with respect to the South. Before cotton, the South had few major ports, almost none of which actively maintained international trade routes or even domestic supply routes. Internal travel and supply was difficult, especially on the waters of the Mississippi River, the main artery of the North American continent, and the eventual gold mine of the South. With the Mississippi’s strong current, deadly undertow, and constant sharp turns, sandbars, and subsystems, navigation was difficult and dangerous. The river promised a revolution in trade, transportation, and commerce only if the technology existed to handle its impossible bends and fight against its southbound current. By the 1820s and into the 1830s, small ships could successfully navigate their way to New Orleans from as far north as Memphis and even St. Louis, if they so dared. But the problem was getting back. Most often, traders and sailors scuttled their boats on landing in New Orleans, selling the wood for a quick profit or a journey home on a wagon or caravan.

棉花改变了这一切,至少在南方是如此。在棉花之前,南方几乎没有大型港口,几乎所有港口都没有积极维护国际贸易航线,甚至没有国内的供应航线。内部的旅行和供应非常困难,尤其是在密西西比河上,这条北美大陆的主要交通线,后来也成为了南方的金矿。由于密西西比河湍急的水流、致命的暗流、不断的急转弯、沙洲和其他障碍,航行变得既困难又危险。河流承诺带来贸易、运输和商业的革命,前提是有足够的技术来应对它那无法预测的弯道并抗衡它向南流动的水流。到了1820年代和1830年代初期,小型船只能够成功地从孟菲斯甚至圣路易斯一路航行到新奥尔良,尽管这需要勇气。但问题在于返回。大多数时候,商人和水手们在新奥尔良登陆后会将船只凿沉,然后卖掉木材,换取快速的利润,或者用马车或商队回家。

The rise of cotton benefited from a change in transportation technology that aided and guided the growth of southern cotton into one of the world’s leading commodities. In January 1812, a 371-ton ship called the New Orleans arrived at its namesake city from the distant internal port of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. This was the first steamboat to navigate the internal waterways of the North American continent from one end to the other and remain capable of returning home. The technology was far from perfect—the New Orleans sank two years later after hitting a submerged sandbar covered in driftwood—but its successful trial promised a bright, new future for river-based travel.

棉花的兴起得益于运输技术的变革,这一变革促进了南方棉花成为世界主要商品之一的增长。1812年1月,一艘名为《新奥尔良号》的371吨重的船只从遥远的内陆港口宾夕法尼亚州匹兹堡出发,抵达了以其命名的新奥尔良市。这是第一艘能够横跨北美大陆内河航道,并且能够顺利返航的蒸汽船。尽管这一技术远未完美——《新奥尔良号》在两年后因撞上一个被漂浮木材覆盖的水下沙洲而沉没——但它的成功试航为基于河流的旅行提供了光明的未来。

And that future was, indeed, bright. Just five years after the New Orleans arrived in its city, 17 steamboats ran regular upriver lines. By the mid-1840s, more than 700 steamboats did the same. In 1860, the port of New Orleans received and unloaded 3,500 steamboats, all focused entirely on internal trade. These boats carried around 160,000 tons of raw product that merchants, traders, and agents converted into nearly $220 million in trade, all in a single year. More than 80 percent of the yield was from cotton alone, the product of the same fields tilled, expanded, and sold over the preceding three decades. Only now, in the 1840s and 1850s, could those fields, plantations, and farms simply load their products onto a boat and wait for the profit, credit, or supplies to return from downriver.

这个未来确实是光明的。《新奥尔良号》抵达新奥尔良市后仅五年,已有17艘蒸汽船开设了定期的上游航线。到了1840年代中期,超过700艘蒸汽船也开始运营类似航线。到1860年,新奥尔良港接收并卸载了3500艘蒸汽船,这些船只完全专注于国内贸易。这些船只运输了约16万吨的原材料,商人、贸易商和代理商将其转化为近2.2亿美元的贸易额,仅一年之内。超过80%的产值来自棉花,而这棉花来自于过去三十年间耕作、扩展和销售的同一片土地。直到1840年代和1850年代,这些田地、种植园和农场才得以将产品简单地装上船,等待来自下游的利润、信贷或供应品的回流。

The explosion of steam power changed the face of the South, and indeed the nation as a whole. Everything that could be steam-powered was steam-powered, sometimes with mixed results. Cotton gins, wagons, grinders, looms, and baths, among countless others, all fell under the net of this new technology. Most importantly, the South’s rivers, lakes, and bays were no longer barriers and hindrances to commerce. Quite the opposite; they had become the means by which commerce flowed, the roads of a modernizing society and region. And most importantly, the ability to use internal waterways connected the rural interior to increasingly urban ports, the sources of raw materials—cotton, tobacco, wheat, and so on—to an eager global market.

蒸汽动力的爆发改变了南方的面貌,甚至影响了整个国家。凡是能使用蒸汽动力的设备几乎都被改造为蒸汽驱动,但有时效果好坏参半。从轧棉机、马车、研磨机、织布机到浴池等,无数设备都采用了这项新技术。最重要的是,南方的河流、湖泊和海湾不再是商业发展的障碍,反而成为了商业流通的渠道,成为这个日益现代化的社会和地区的“道路”。更关键的是,内河航运的便利使得乡村腹地与日益发展的城市港口紧密相连,将棉花、烟草、小麦等原材料源源不断地输送到渴求商品的全球市场。

Coastal ports like New Orleans, Charleston, Norfolk, and even Richmond became targets of steamboats and coastal carriers. Merchants, traders, skilled laborers, and foreign speculators and agents flooded the towns. In fact, the South experienced a greater rate of urbanization between 1820 and 1860 than the seemingly more industrial, urban-based North. Urbanization of the South simply looked different from that seen in the North and in Europe. Where most northern and some European cities (most notably London, Liverpool, Manchester, and Paris) developed along the lines of industry, creating public spaces to boost the morale of wage laborers in factories, on the docks, and in storehouses, southern cities developed within the cyclical logic of sustaining the trade in cotton that justified and paid for the maintenance of an enslaved labor force. The growth of southern cities, then, allowed slavery to flourish and brought the South into a more modern world.

新奥尔良、查尔斯顿、诺福克,甚至里士满等沿海港口,成为了蒸汽船和沿海运输船的目标。商人、贸易商、技术工人以及外国投机商和代理人纷纷涌入这些城镇。事实上,在1820年至1860年间,南方的城市化率甚至超过了看似更加工业化、以城市为基础的北方。不过,南方的城市化进程与北方和欧洲的情况有所不同。北方及部分欧洲城市(尤其是伦敦、利物浦、曼彻斯特和巴黎)主要沿着工业化发展,其公共空间的建设旨在提升工厂、码头和仓库中蓝领工人的士气。而南方城市的扩张则围绕着维持棉花贸易这一循环逻辑展开,而棉花贸易正是奴隶制存在的经济支柱,并为奴隶劳动力的维护提供资金。因此,南方城市的增长不仅促进了奴隶制度的繁荣,也推动了南方迈向更现代化的世界。

Between 1820 and 1860, quite a few southern towns experienced dramatic population growth, which paralleled the increase in cotton production and international trade to and from the South. The 27,176 people New Orleans claimed in 1820 expanded to more than 168,000 by 1860. In fact, in New Orleans, the population nearly quadrupled from 1830 to 1840 as the Cotton Revolution hit full stride. At the same time, Charleston’s population nearly doubled, from 24,780 to 40,522; Richmond expanded threefold, growing from a town of 12,067 to a capital city of 37,910; and St. Louis experienced the largest increase of any city in the nation, expanding from a frontier town of 10,049 to a booming Mississippi River metropolis of 160,773.

1820年至1860年间,南方不少城镇的人口增长迅猛,这一趋势与棉花产量的提高及南方对外贸易的增长相呼应。新奥尔良的人口从1820年的27,176人增长到1860年的超过168,000人。事实上,随着棉花革命全面展开,新奥尔良的人口在1830年至1840年间几乎翻了两番。同时,查尔斯顿的人口从24,780人增长到40,522人,几乎翻倍;里士满的人口增长了三倍,从一个拥有12,067人的小镇发展为拥有37,910人的州府城市;而圣路易斯的人口增长幅度更是全美之最,从一个边境小镇(10,049人)迅速膨胀为密西西比河沿岸繁华的都会(160,773人)。

The city and the field, the urban center and the rural space, were inextricably linked in the decades before the Civil War. And that relationship connected the region to a global market and community. As southern cities grew, they became more cosmopolitan, attracting types of people either unsuited for or uninterested in rural life. These people—merchants, skilled laborers, traders, sellers of all kinds and colors—brought rural goods to a market desperate for raw materials. Everyone, it seemed, had a place in the cotton trade. Agents, many of them transients from the North, and in some cases Europe, represented the interests of planters and cotton farmers in the cities, making connections with traders who in turn made deals with manufactories in the Northeast, Liverpool, and Paris.

在内战前的几十年里,城市与乡村、都市中心与农村地区密不可分,而这种联系又将南方地区融入全球市场和国际社会。随着南方城市的扩张,它们变得更加国际化,吸引了那些不适应或不愿意从事农村生活的人。这些人——商人、技工、贸易商,以及各类商品的买卖者——将乡村的商品带入对原材料需求迫切的市场。似乎每个人都能在棉花贸易中找到自己的位置。代理商——其中许多来自北方,甚至欧洲——代表种植园主和棉农的利益,在城市里与贸易商建立联系,而这些贸易商又与东北部、利物浦和巴黎的工厂达成交易。

Among the more important aspects of southern urbanization was the development of a middle class in the urban centers, something that never fully developed in the more rural areas. In a very general sense, the rural South fell under a two-class system in which a landowning elite controlled the politics and most of the capital, and a working poor survived on subsistence farming or basic, unskilled labor funded by the elite. The development of large urban centers founded on trade, and flush with transient populations of sailors, merchants, and travelers, gave rise to a large, highly developed middle class in the South. Predicated on the idea of separation from those above and below them, middle-class men and women in the South thrived in the active, feverish rush of port city life.

南方城市化进程中一个重要的方面是城市中产阶级的形成,而这在更为乡村化的地区从未真正发展起来。总体而言,农村南方大致遵循一种两级社会结构,土地所有精英掌控政治和大部分资本,而贫苦劳动者则依靠自给农业或由精英阶层资助的基础、非技术性劳动维生。然而,建立在贸易基础上的大型城市中心,以及由水手、商人和旅人组成的流动人口,使得南方催生出一个庞大且高度发展的中产阶级。南方的中产阶级男女以与上层和下层社会保持区隔为原则,在港口城市活跃、繁忙的生活节奏中蓬勃发展。

Skilled craftsmen, merchants, traders, speculators, and store owners made up the southern middle class. Fashion trends that no longer served their original purpose—such as a broad-brimmed hat to protect one from the sun, knee-high boots for horse riding, and linen shirts and trousers to fight the heat of an unrelenting sun—lost popularity at an astonishing rate. Silk, cotton, and bright colors came into vogue, especially in coastal cities like New Orleans and Charleston; cravats, golden brooches, diamonds, and “the best stylings of Europe” became the standards of urban middle-class life in the South. Neighbors, friends, and business partners formed and joined the same benevolent societies. These societies worked to aid the less fortunate in society, the orphans, the impoverished, the destitute. But in many cases these benevolent societies simply served as a way to keep other people out of middle-class circles, sustaining both wealth and social prestige within an insular, well-regulated community. Members and partners married each others’ sisters, stood as godparents for each others’ children, and served, when the time came, as executors of fellow members’ wills.

熟练工匠、商人、贸易商、投机者和店主构成了南方的中产阶级。许多曾因实用性而流行的服饰迅速失去市场,例如用于遮阳的宽边帽、骑马时穿的过膝长靴,以及抵御酷热阳光的亚麻衬衫和长裤。在新奥尔良和查尔斯顿等沿海城市,丝绸、棉布和鲜艳的色彩开始流行,领巾、金胸针、钻石以及“欧洲最时髦的装扮”成为南方城市中产阶级生活的标配。邻里、朋友和商业伙伴纷纷加入相同的慈善协会,这些组织旨在帮助社会中的弱势群体,如孤儿、贫困者和无依无靠者。然而,在许多情况下,这些慈善协会只是用来将他人排除在中产阶级圈子之外,从而在一个封闭且严格规范的社群内维持财富和社会声望。会员及其家人彼此通婚,互相为对方子女担任教父母,并在必要时担任遗嘱执行人,以确保财富与地位的延续。

The city bred exclusivity. That was part of the rush, part of fever of the time. Built upon the cotton trade, funded by European and Northeastern merchants, markets, and manufactories, Southern cities became headquarters of the nation’s largest and most profitable commodities—cotton and enslaved people. And they welcomed the world with open checkbooks and open arms.

城市孕育了排他性,这正是当时狂热氛围的一部分。南方城市建立在棉花贸易之上,由欧洲和美国东北部的商人、市场和工厂提供资金,成为全美最大、最盈利商品——棉花与奴隶——的中心。这些城市敞开支票簿和双臂,热情迎接来自世界各地的商机。

V. Southern Cultures

五、南方文化

To understand the global and economic functions of the South, we also must understand the people who made the whole thing work. The South, more than perhaps any other region in the United States, had a great diversity of cultures and situations. The South still relied on the existence of slavery; and as a result, it was home to nearly 4 million enslaved people by 1860, amounting to more than 45 percent of the entire Southern population. Naturally, these people, though fundamentally unfree in their movement, developed a culture all their own. They created kinship and family networks, systems of (often illicit) trade, linguistic codes, religious congregations, and even benevolent and social aid organizations—all within the grip of slavery, a system dedicated to extraction rather than development, work and production rather than community and emotion.

要理解南方的全球性与经济职能,我们也必须了解支撑这一切的人群。南方比美国其他任何地区都更加多元化,同时,它仍然依赖奴隶制的存在。因此,到1860年,南方的奴隶人口已接近400万,占整个南方人口的45%以上。尽管这些人无法自由行动,但他们仍在奴隶制度的桎梏下发展出了独特的文化。他们建立了亲属和家庭网络,形成了(通常是非法的)贸易体系,创造了独特的语言编码,组织了宗教聚会,甚至建立了慈善和社会援助机构——所有这些都在一个以剥削为核心、以劳动和生产为目标,而非社区与情感发展的制度下形成。

The concept of family, more than anything else, played a crucial role in the daily lives of enslaved people. Family and kinship networks, and the benefits they carried, represented an institution through which enslaved people could piece together a sense of community, a sense of feeling and dedication, separate from the forced system of production that defined their daily lives. The creation of family units, distant relations, and communal traditions allowed enslaved people to maintain religious beliefs, ancient ancestral traditions, and even names passed down from generation to generation in a way that challenged enslavement. Ideas passed between relatives on different plantations, names given to children in honor of the deceased, and basic forms of love and devotion created a sense of individuality, an identity that assuaged the loneliness and desperation of enslaved life. Family defined how each plantation, each community, functioned, grew, and labored.

家庭观念,比任何其他因素都更深刻地影响着奴隶的日常生活。家庭和亲属网络,以及它们所带来的情感纽带,构成了奴隶群体建立社区意识、情感寄托和相互承诺的重要途径,使他们在被强迫劳动的生活之外,仍能找到一丝归属感。家庭单位、远亲关系和社区传统的建立,使奴隶得以保留宗教信仰、古老的祖先传统,甚至能够代代相传姓名,以此对抗奴役制度的压迫。不同种植园的亲属之间交流思想,孩子的名字被用来纪念逝去的亲人,而日常生活中的爱与陪伴,则帮助他们维系个体意识,使奴役生活中的孤独与绝望得以缓解。家庭决定了每个种植园、每个社区的运作方式、发展模式以及劳动组织形式。

Nothing under slavery lasted long, at least not in the same form. Enslaved families and networks were no exceptions to this rule. African-born enslaved people during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries engaged in marriages—sometimes polygamous—with those of the same ethnic groups whenever possible. This, most importantly, allowed for the maintenance of cultural traditions, such as language, religion, name practices, and even the rare practice of bodily scaring. In some parts of the South, such as Louisiana and coastal South Carolina, ethnic homogeneity thrived, and as a result, traditions and networks survived relatively unchanged for decades. As the number of enslaved people arriving in the United States increased, and generations of American-born enslaved laborers overtook the original African-born populations, the practice of marriage, especially among members of the same ethnic group, or even simply the same plantation, became vital to the continuation of aging traditions. Marriage served as the single most important aspect of cultural and identity formation, as it connected enslaved people to their own pasts, and gave some sense of protection for the future. By the start of the Civil War, approximately two-thirds of enslaved people were members of nuclear households, each household averaging six people—mother, father, children, and often a grandparent, elderly aunt or uncle, and even “in-laws.” Those who did not have a marriage bond, or even a nuclear family, still maintained family ties, most often living with a single parent, brother, sister, or grandparent.

在奴隶制下,没有什么能长久存在,至少不会保持原样。奴隶家庭和亲属网络也不例外。在十七世纪和十八世纪,非洲出生的奴隶在可能的情况下,常常与同一族群的人结婚,有时是多妻制。这最重要的作用是维系文化传统,比如语言、宗教、命名习惯,甚至包括少数的身体刻痕实践。在南方的一些地区,如路易斯安那和南卡罗来纳州的沿海地区,族群同质性较强,因此,文化传统和社会网络得以相对不变地延续了几十年。随着抵达美国的奴隶人数增加,美国出生的奴隶逐渐取代了原先的非洲出生的奴隶,结婚,尤其是在同一族群或甚至同一种植园内结婚,成为了维持这些传统的关键。婚姻成为文化和身份形成中最为重要的部分,它将奴隶与过去的文化联系在一起,并为未来提供了一定的保护。到内战爆发时,约三分之二的奴隶属于核心家庭,每个家庭通常有六人——父母、孩子,常常还包括祖父母、年老的姑姑或叔叔,甚至是“姻亲”。那些没有婚姻关系或没有核心家庭的人,依然保持着家庭联系,他们大多与单亲、兄弟姐妹或祖父母一起生活。

Many marriages between enslaved people endured for many years. But the threat of disruption, often through sale, always loomed. As the internal slave trade increased following the constitutional ban on slave importation in 1808 and the rise of cotton in the 1830s and 1840s, enslaved families, especially those established prior to arriving in the United States, came under increased threat. Hundreds of thousands of marriages, many with children, fell victim to sale “downriver”—a euphemism for the near constant flow of enslaved laborers down the Mississippi River to the developing cotton belt in the Southwest. In fact, during the Cotton Revolution alone, between one-fifth and one-third of all marriages between enslaved people were broken up through sale or forced migration. But this was not the only threat. Planters, and enslavers of all shapes and sizes, recognized that marriage was, in the most basic and tragic sense, a privilege granted and defined by them for their enslaved laborers. And as a result, many enslavers used’ marriages, or the threats thereto, to squeeze out more production, counteract disobedience, or simply make a gesture of power and superiority.

许多奴隶之间的婚姻持续了多年。然而,破裂的威胁始终存在,通常是因为被出售。随着1808年宪法禁止进口奴隶以及1830年代和1840年代棉花产业的崛起,奴隶家庭,尤其是那些在抵达美国之前就已经建立的家庭,面临着越来越大的威胁。成千上万的婚姻,许多伴有子女的家庭,成为了“下河”(这个词语是指奴隶劳工被运送至下游的密西西比河,前往新兴的南方棉花带)的牺牲品。实际上,仅在棉花革命期间,约五分之一到三分之一的奴隶婚姻因出售或强迫迁移而被打破。但这并非唯一的威胁。种植园主和各种形式的奴隶主认识到,婚姻在最基本和最悲惨的意义上,是由他们授予并定义的奴隶劳工的特权。因此,许多奴隶主利用婚姻或威胁婚姻来榨取更多的生产力,制止不服从,或单纯地展示他们的权力和优越感。

Threats to family networks, marriages, and household stability did not stop with the death of an enslaver. An enslaved couple could live their entire lives together, even having been born, raised, and married on the slave plantation, and, following the death of their enslaver, find themselves at opposite sides of the known world. It only took a single relative, executor, creditor, or friend of the deceased to make a claim against the estate to cause the sale and dispersal of an entire enslaved community.

对家庭网络、婚姻和家庭稳定性的威胁并未因奴隶主的去世而停止。一对奴隶夫妇可能终其一生一直生活在一起,甚至在奴隶种植园上出生、成长并结婚,但在奴隶主去世后,他们却可能被迫分离,生活在世界的两端。只需一个亲戚、执行人、债权人或亡者的朋友提出对遗产的要求,就可能导致整个奴隶社区的被出售和分散。

Enslaved women were particularly vulnerable to the shifts of fate attached to slavery. In many cases, enslaved women did the same work as men, spending the day—from sun up to sun down—in the fields picking and bundling cotton. In some rare cases, especially among the larger plantations, planters tended to use women as house servants more than men, but this was not universal. In both cases, however, enslaved women’s experiences were different than their male counterparts, husbands, and neighbors. Sexual violence, unwanted pregnancies, and constant childrearing while continuing to work the fields all made life as an enslaved woman more prone to disruption and uncertainty. Harriet Jacobs, an enslaved woman from North Carolina, chronicled her enslaver’s attempts to sexually abuse her in her narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Jacobs suggested that her successful attempts to resist sexual assault and her determination to love whom she pleased was “something akin to freedom.” But this “freedom,” however empowering and contextual, did not cast a wide net. Many enslaved women had no choice concerning love, sex, and motherhood. On plantations, small farms, and even in cities, rape was ever-present. Like the splitting of families, enslavers used sexual violence as a form of terrorism, a way to promote increased production, obedience, and power relations. And this was not restricted only to unmarried women. In numerous contemporary accounts, particularly violent enslavers forced men to witness the rape of their wives, daughters, and relatives, often as punishment, but occasionally as a sadistic expression of power and dominance.

奴隶制下,奴隶女性尤为脆弱,命运的变化更加无常。在许多情况下,奴隶女性与男性做着同样的工作,从早到晚都在田间采摘和捆绑棉花。在一些大型种植园中,奴隶主倾向于将女性当作家佣使用,但这并非普遍现象。然而,无论是在哪种情况,奴隶女性的经历总是与男性奴隶、丈夫和邻居不同。性暴力、非自愿的怀孕和在继续从事农活的同时抚养孩子,使得作为一名奴隶女性的生活更容易遭遇动荡和不确定性。来自北卡罗来纳州的奴隶女性哈丽雅特·雅各布斯在她的叙述《奴隶女孩的生活经历》中记载了她的奴隶主试图性侵她的经历。雅各布斯表示,她成功抵抗性侵并坚持按照自己的意愿去爱人的行为“有些类似于自由”。然而,这种“自由”虽然具有赋权作用且在特定情境下具有意义,但并未普及到所有奴隶女性。许多奴隶女性在爱情、性和母亲身份上毫无选择权。在种植园、小农场甚至城市里,强奸时常发生。与家庭分裂一样,奴隶主将性暴力作为恐怖手段,借此提高生产力、强制服从并维持权力关系。这种情况不仅限于未婚女性。在许多当时的记载中,尤其是暴力的奴隶主常强迫男性目睹他们的妻子、女儿和亲戚遭到强奸,往往是作为惩罚,有时则是出于施虐的权力和支配欲。

As property, enslaved women had no recourse, and society, by and large, did not see a crime in this type of violence. Racist pseudo-scientists claimed that whites could not physically rape Africans or African Americans, as the sexual organs of each were not compatible in that way. State law, in some cases, supported this view, claiming that rape could only occur between either two white people or a Black man and a white woman. All other cases fell under a silent acceptance. The consequences of rape, too, fell to enslaved victimes. Pregnancies that resulted from rape did not always lead to a lighter workload for the mother. And if an enslaved woman acted out against a rapist, whether that be her enslaver or any other white attacker, her actions were seen as crimes rather than desperate acts of survival. For example, a 19-year-old enslaved woman named Celia fell victim to repeated rape by her enslaver in Callaway County, Missouri. Between 1850 and 1855, Robert Newsom raped Celia hundreds of times, producing two children and several miscarriages. Sick and desperate in the fall of 1855, Celia took a club and struck her enslaver in the head, killing him. But instead of sympathy and aid, or even an honest attempt to understand and empathize, the community called for the execution of Celia. On November 16, 1855, after a trial of ten days, Celia, the 19-year-old rape victim and slave, was hanged for her crimes against her enslaver.

作为财产,奴隶女性无法寻求任何救济,社会普遍不认为这种暴力行为构成犯罪。种族主义伪科学家声称,白人无法对非洲人或非裔美国人实施强奸,因为彼此的生殖器在身体上不兼容。在某些情况下,州法律甚至支持这一观点,认为强奸只能发生在两个白人之间,或者一个黑人男性和一位白人女性之间。所有其他案件都被默许接受。强奸的后果也由奴隶受害者承担。由于强奸而怀孕的奴隶女性,通常并不会因此减轻工作负担。如果一名奴隶女性反抗强奸犯,无论是她的奴隶主还是其他任何白人侵害者,她的行为都会被视为犯罪,而不是生存的绝望举动。例如,一位名叫塞利亚(Celia)的19岁奴隶女性在密苏里州卡拉威县成为她奴隶主反复强奸的受害者。从1850年到1855年,罗伯特·纽瑟姆(Robert Newsom)对塞利亚实施了数百次强奸,导致她怀上两个孩子并发生多次流产。1855年秋天,塞利亚身心俱疲、绝望至极,她拿起一根木棒击打奴隶主的头部,致其死亡。然而,社会并没有给予同情和帮助,甚至没有试图理解和同情她。相反,社会要求处决塞利亚。1855年11月16日,在十天的审判后,这位19岁的强奸受害者和奴隶被以“对奴隶主犯罪”罪名绞死。

Gender inequality did not always fall along the same lines as racial inequality. Southern society, especially in the age of cotton, deferred to white men, under whom laws, social norms, and cultural practices were written, dictated, and maintained. White and free women of color lived in a society dominated, in nearly every aspect, by men. Denied voting rights, women, of all statuses and colors, had no direct representation in the creation and discussion of law. Husbands, it was said, represented their wives, as the public sphere was too violent, heated, and high-minded for women. Society expected women to represent the foundations of the republic, gaining respectability through their work at home, in support of their husbands and children, away from the rough and boisterous realm of masculinity. In many cases, too, law did not protect women the same way it protected men. In most states, marriage, an act expected of any self-respecting, reasonable woman of any class, effectively transferred all of a woman’s property to her husband, forever, regardless of claim or command. Divorce existed, but it hardly worked in a woman’s favor, and often, if successful, ruined the wife’s standing in society, and even led to well-known cases of suicide.

性别不平等并不总是与种族不平等完全一致。在棉花经济的时代,南方社会尤为服从于白人男性,他们制定、主导并维护了法律、社会规范和文化实践。白人女性和自由有色人种女性生活在一个几乎所有方面都由男性主导的社会中。无论地位如何,女性都被剥夺了投票权,无法直接参与法律的制定和讨论。人们认为,丈夫代表妻子,因为公共领域太过暴力、激烈且高高在上,不适合女性。社会期望女性代表共和国家的基础,通过在家中的工作、支持丈夫和孩子来赢得尊重,远离粗暴喧嚣的男性领域。在许多情况下,法律也没有像保护男性那样保护女性。在大多数州,结婚这一行为(无论阶级如何,几乎是每个自尊的女性应当履行的责任)实际上将女性所有的财产转移给了丈夫,且这种转移是永久的,无论女性是否同意或命令。离婚虽然存在,但几乎从未对女性有利,且如果成功,往往会摧毁妻子在社会中的地位,甚至导致众所周知的自杀案件。

Life on the ground in cotton South, like the cities, systems, and networks within which it rested, defied the standard narrative of the Old South. Slavery existed to dominate, yet enslaved people formed bonds, maintained traditions, and crafted new culture. They fell in love, had children, and protected one another using the privileges granted them by their captors, and the basic intellect allowed all human beings. They were resourceful, brilliant, and vibrant, and they created freedom where freedom seemingly could not exist. And within those communities, resilience and dedication often led to cultural sustenance. Among the enslaved, women, and the impoverished-but-free, culture thrived in ways that are difficult to see through the bales of cotton and the stacks of money sitting on the docks and in the counting houses of the South’s urban centers. But religion, honor, and pride transcended material goods, especially among those who could not express themselves that way.

在棉花种植的南方,像城市、系统和网络一样,生活本身也挑战了传统的旧南方叙事。奴隶制度的存在是为了支配,但奴隶们依然建立了联系,维持传统,创造了新的文化。他们相爱,生子,互相保护,利用奴隶主赋予他们的特权,以及所有人类所拥有的基本智慧。他们富有创造力、聪明且充满活力,在看似无法存在自由的地方创造了自由。在这些社区中,韧性与奉献往往导致了文化的维持。在奴隶、女性以及贫困但自由的人们之间,文化以一种难以通过棉花堆和南方城市中心码头与计帐房内的金钱堆积来观察的方式蓬勃发展。但宗教、荣誉和自豪感超越了物质财富,尤其是在那些无法以物质方式表达自己的人们中间。

VI. Religion and Honor in the Slave South

六、奴隶制南方的宗教与荣誉

Economic growth, violence, and exploitation coexisted and mutually reinforced evangelical Christianity in the South. The revivals of the Second Great Awakening established the region’s prevailing religious culture. Led by Methodists, Baptists, and to a lesser degree, Presbyterians, this intense period of religious regeneration swept the along southern backcountry. By the outbreak of the Civil War, the vast majority of southerners who affiliated with a religious denomination belonged to either the Baptist or Methodist faith. Both churches in the South briefly attacked slavery before transforming into some of the most vocal defenders of slavery and the southern social order.

经济增长、暴力和剥削与南方的福音派基督教共同存在,并相互加强。第二次伟大觉醒的复兴运动确立了该地区主导的宗教文化。在卫理公会、浸信会和在一定程度上长老会的领导下,这一激烈的宗教复兴时期席卷了南方的偏远地区。到南北战争爆发时,绝大多数南方与某一宗教教派有联系的人都属于浸信会或卫理公会。南方的这两大教会曾短暂地反对奴隶制,但随后转变为奴隶制和南方社会秩序的最强烈支持者之一。

Southern ministers contended that God himself had selected Africans for bondage but also considered the evangelization of enslaved people to be one of their greatest callings. Missionary efforts among enslaved southerners largely succeeded and Protestantism spread rapidly among African Americans, leading to a proliferation of biracial congregations and prominent independent Black churches. Some Black and white southerners forged positive and rewarding biracial connections; however, more often Black and white southerners described strained or superficial religious relationships.

南方的牧师主张,上帝亲自选择了非洲人作为奴隶,但同时也认为传教给奴隶是他们最伟大的使命之一。南方奴隶中的传教工作取得了显著成功,基督教新教在非洲裔美国人中迅速传播,导致了多种种族混合的教会以及显著的独立黑人教会的出现。一些黑人和白人南方人建立了积极而有益的种族关系;然而,更多的黑人和白人南方人则描述了紧张或表面化的宗教关系。

As the institution of slavery hardened racism in the South, relationships between missionaries and Native Americans transformed as well. Missionaries of all denominations were among the first to represent themselves as “pillars of white authority.” After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, plantation culture expanded into the Deep South, and mission work became a crucial element of Christian expansion. Frontier mission schools carried a continual flow of Christian influence into Native American communities. Some missionaries learned Indigenous languages, but many more worked to prevent Indigenous children from speaking their native tongues, insisting on English for Christian understanding. By the Indian removals of 1835 and the Trail of Tears in 1838, missionaries in the South preached a pro-slavery theology that emphasized obedience to enslavers, the biblical basis of racial slavery via the curse of Ham, and the “civilizing” paternalism of enslavers.

随着奴隶制在南方加剧了种族主义,传教士与美洲土著的关系也发生了变化。各个教派的传教士成为了最早自我表述为“白人权威支柱”的群体之一。在1803年路易斯安那购地之后,种植园文化扩展到了南方深处,传教工作成为基督教扩展的重要组成部分。边疆的传教学校将基督教的影响源源不断地带入了土著社区。一些传教士学习了土著语言,但更多的人则致力于阻止土著儿童讲他们的母语,强调使用英语以便理解基督教教义。到了1835年的印第安人迁移和1838年的眼泪之路时,南方的传教士开始宣讲亲奴隶制的神学,强调服从奴隶主、通过“哈姆的诅咒”建立种族奴隶制的圣经依据以及奴隶主的“文明化”父权主义。

Enslaved people most commonly received Christian instruction from white preachers or enslavers, whose religious message typically stressed the subservience of enslaved people. Anti-literacy laws ensured that most enslaved people would be unable to read the Bible in its entirety and thus could not acquaint themselves with such inspirational stories as Moses delivering the Israelites out of slavery. Contradictions between God’s Word and enslavers’ cruelty did not pass unnoticed by many enslaved African Americans. As formerly enslaved person William Wells Brown declared, “slaveholders hide themselves behind the Church,” adding that “a more praying, preaching, psalm-singing people cannot be found than the slaveholders of the South.”

被奴役的人通常接受白人传教士或奴隶主的基督教教义,这些教义通常强调奴隶的服从性。反文盲法确保大多数被奴役的人无法完全读懂圣经,因此他们无法接触到像摩西带领以色列人脱离奴役这样的鼓舞人心的故事。许多被奴役的非裔美国人注意到了上帝的话语与奴隶主残酷行为之间的矛盾。正如曾经被奴役的人威廉·韦尔斯·布朗所说:“奴隶主藏身于教会背后,”他还补充道:“没有比南方的奴隶主更会祈祷、讲道、唱圣诗的了。”

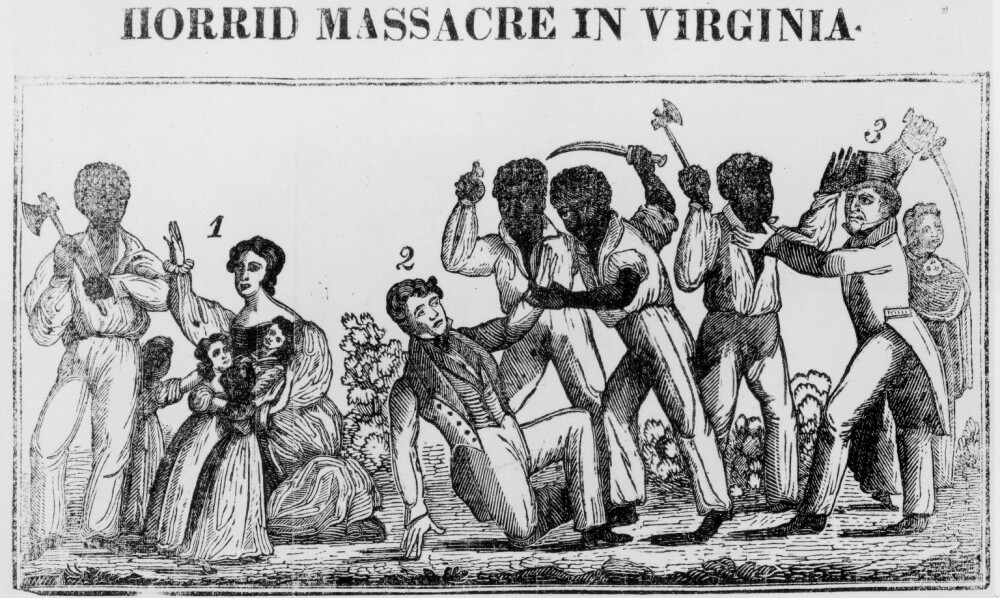

Many enslaved people chose to create and practice their own versions of Christianity, one that typically incorporated aspects of traditional African religions with limited input from the white community. Nat Turner, the leader of the great slave rebellion, found inspiration from religion early in life. Adopting an austere Christian lifestyle during his adolescence, Turner claimed to have been visited by “spirits” during his twenties and considered himself something of a prophet. He claimed to have had visions, in which he was called on to do the work of God, leading some contemporaries (as well as historians) to question his sanity.

许多被奴役的人选择创造并实践自己版本的基督教,这些版本通常融合了传统非洲宗教的元素,并且很少受到白人社区的影响。大奴隶起义的领袖纳特·特纳(Nat Turner)早年就从宗教中获得了启发。特纳在青少年时期就过着严格的基督教生活,他声称在二十多岁时曾受到“神灵”的拜访,并自认为是一位先知。他表示自己曾有过异象,认为自己被召唤去完成上帝的工作,这使得一些同时代人(以及历史学家)开始质疑他的理智。

Inspired by his faith, Turner led the most deadly slave rebellion in the antebellum South. On the morning of August 22, 1831, in Southampton County, Virginia, Nat Turner and six collaborators attempted to free the region’s enslaved population. Turner initiated the violence by killing his enslaver with an ax blow to the head. By the end of the day, Turner and his band, which had grown to over fifty men, killed fifty-seven white men, women, and children on eleven farms. By the next day, the local militia and white residents had captured or killed all of the participants except Turner, who hid for a number of weeks in nearby woods before being captured and executed. The white terror that followed Nat Turner’s rebellion transformed southern religion, as anti-literacy laws increased and Black-led churches were broken up and placed under the supervision of white ministers.

受信仰启发,特纳领导了南北战争前最致命的奴隶起义。1831年8月22日早晨,在弗吉尼亚州南安普敦县,纳特·特纳和六名同伙试图解放该地区的奴隶人口。特纳通过用斧头击打其奴隶主的头部开始了暴力行动。到当天结束时,特纳和他的队伍已发展到五十多人,他们在十一座农场上杀害了五十七名白人男女和儿童。次日,当地民兵和白人居民逮捕或杀死了所有参与者,除了特纳,他在附近的森林中藏匿了数周,最终被捕并执行了死刑。特纳起义之后的白人恐怖改变了南方的宗教局面,反文盲法日益严格,黑人主导的教堂被解散,并置于白人牧师的监管之下。

Evangelical religion also shaped understandings of what it meant to be a southern man or a southern woman. Southern manhood was largely shaped by an obsession with masculine honor, whereas southern womanhood centered on expectations of sexual virtue or purity. Honor prioritized the public recognition of white masculine claims to reputation and authority. Southern men developed a code to ritualize their interactions with each other and to perform their expectations of honor. This code structured language and behavior and was designed to minimize conflict. But when conflict did arise, the code also provided rituals that would reduce the resulting violence.

福音派宗教也塑造了人们对南方男性和女性身份的理解。南方男性气概在很大程度上受到对男子气概荣誉的执着,而南方女性气概则集中于对性别贞洁或纯洁的期望。荣誉强调了白人男性在声誉和权威上的公开认同。南方男性发展出了一套规范,通过这种规范来仪式化彼此之间的互动,并表现出他们对荣誉的期望。这套规范塑造了语言和行为,并旨在最小化冲突。但当冲突发生时,这套规范也提供了减少暴力的仪式。

The formal duel exemplified the code in action. If two men could not settle a dispute through the arbitration of their friends, they would exchange pistol shots to prove their equal honor status. Duelists arranged a secluded meeting, chose from a set of deadly weapons, and risked their lives as they clashed with swords or fired pistols at one another. Some of the most illustrious men in American history participated in a duel at some point during their lives, including President Andrew Jackson, Vice President Aaron Burr, and U.S. senators Henry Clay and Thomas Hart Benton. In all but Burr’s case, dueling helped elevate these men to prominence.

正式的决斗是这一行为规范的典型体现。如果两名男子无法通过朋友的调解解决争端,他们便会通过交换手枪射击来证明自己在荣誉上的平等地位。决斗者会安排一个隐秘的会面地点,从一套致命的武器中选择,然后以剑相搏或互相开枪,冒着生命危险。美国历史上一些最著名的人物曾在一生中参与过决斗,包括总统安德鲁·杰克逊、副总统亚伦·伯尔、以及美国参议员亨利·克莱和托马斯·哈特·本顿。除了伯尔之外,决斗在其他人的案例中帮助他们提升了名声。

Violence among the lower classes, especially those in the backcountry, involved fistfights and shoot-outs. Tactics included the sharpening of fingernails and filing of teeth into razor-sharp points, which would be used to gouge eyes and bite off ears and noses. In a duel, a gentleman achieved recognition by risking his life rather than killing his opponent, whereas those involved in rough-and-tumble fighting achieved victory through maiming their opponent.

在下层阶级中,尤其是那些生活在边远地区的人,暴力表现为拳打脚踢和决斗。战术包括将指甲磨尖、将牙齿磨成锋利的尖点,利用这些武器来挖眼睛或咬掉耳朵和鼻子。在决斗中,一位绅士通过冒着生命危险而非杀死对方来赢得荣誉,而那些参与粗暴斗殴的人则通过使对方残废来获得胜利。

The legal system was partially to blame for the prevalence of violence in the Old South. Although states and territories had laws against murder, rape, and various other forms of violence, including specific laws against dueling, upper-class southerners were rarely prosecuted, and juries often acquitted the accused. Despite the fact that hundreds of duelists fought and killed one another, there is little evidence that many duelists faced prosecution, and only one, Timothy Bennett (of Belleville, Illinois), was ever executed. By contrast, prosecutors routinely sought cases against lower-class southerners, who were found guilty in greater numbers than their wealthier counterparts.

法律制度在旧南方暴力现象的普遍存在中也有一定责任。尽管各州和领地有针对谋杀、强奸以及其他各种暴力行为的法律,包括专门针对决斗的法律,但上层阶级的南方人很少受到起诉,陪审团通常会宣判被告无罪。尽管成百上千的决斗者互相对抗并致死,但几乎没有证据表明很多决斗者面临起诉,只有一位名叫提摩太·本内特(来自伊利诺伊州贝尔维尔)的决斗者被处决。相比之下,检察官经常追究下层南方人的案件,后者的有罪率远高于更富裕的对手。

The southern emphasis on honor affected women as well. While southern men worked to maintain their sense of masculinity; so too southern women cultivated a sense of femininity. Femininity in the South was intimately tied to the domestic sphere, even more so than for women in the North. The cult of domesticity strictly limited the ability of wealthy southern women to engage in public life. While northern women began to organize reform societies, southern women remained bound to the home, where they were instructed to cultivate their families’ religious sensibility and manage their household. Managing the household was not easy work, however. For women on large plantations, managing the household would include directing a large bureaucracy of potentially rebellious enslaved people. For most southern women who did not live on plantations, managing the household included nearly constant work in keeping families clean, fed, and well-behaved. On top of these duties, many southern women were required to help with agricultural tasks.

南方对荣誉的重视也影响了女性。尽管南方男性努力保持他们的男子气概,南方女性也在培养她们的女性气质。南方的女性气质与家庭生活密切相关,甚至比北方女性更为明显。家庭崇拜严格限制了富裕南方女性参与公共生活的能力。尽管北方女性开始组织改革团体,南方女性仍然被束缚在家庭中,她们的任务是培养家庭的宗教感情并管理家务。然而,管理家庭并非易事。对于大种植园上的女性来说,管理家庭意味着要指挥一支庞大的可能反抗的奴隶队伍。对于大多数未住在种植园的南方女性来说,管理家庭意味着几乎时刻都要工作,确保家庭成员保持干净、饱食并行为得当。除了这些职责外,许多南方女性还需要帮助农业工作。

Female labor was an important aspect of the southern economy, but the social position of women in southern culture was understood not through economic labor but rather through moral virtue. While men fought to get ahead in the turbulent world of the cotton boom, women were instructed to offer a calming, moralizing influence on husbands and children. The home was to be a place of quiet respite and spiritual solace. Under the guidance of a virtuous woman, the southern home would foster the values required for economic success and cultural refinement. Female virtue came to be understood largely as a euphemism for sexual purity, and southern culture, southern law, and southern violence largely centered on protecting that virtue of sexual purity from any possible imagined threat. In a world saturated with the sexual exploitation of Black women, southerners developed a paranoid obsession with protecting the sexual purity of white women. Black men were presented as an insatiable sexual threat. Racial systems of violence and domination were wielded with crushing intensity for generations, all in the name of keeping white womanhood as pure as the cotton that anchored southern society.

女性劳动是南方经济的重要组成部分,但在南方文化中,女性的社会地位并不是通过经济劳动来理解的,而是通过道德美德来定义的。当男性在动荡的棉花经济中争取前进时,女性则被教导要为丈夫和孩子提供一种平静的、道德化的影响。家庭应该是一个安静的避风港和精神慰藉之地。在一位有德行的女性的引导下,南方的家庭将培养出经济成功和文化精致所需的价值观。女性美德主要被理解为性纯洁的代名词,南方文化、法律和暴力在很大程度上都围绕着保护这一性纯洁的美德不受任何可能的威胁。在一个充斥着对黑人女性性剥削的世界里,南方人对保护白人女性性纯洁的偏执成为了一种病态的迷恋。黑人男性被描绘成无尽的性威胁。种族暴力和统治的体系以压倒性的强度被使用了几代人之久,所有这一切都以保持白人女性的纯洁为名,这种纯洁就像是支撑南方社会的棉花一样。

VII. Conclusion

七、结论

Cotton created the antebellum South. The wildly profitable commodity opened a previously closed society to the grandeur, the profit, the exploitation, and the social dimensions of a larger, more connected, global community. In this way, the South, and the world, benefited from the Cotton Revolution and the urban growth it sparked. But not all that glitters is gold. Slavery remained and the internal slave trade grew to untold heights as the 1860s approached. Politics, race relations, and the burden of slavery continued beneath the roar of steamboats, countinghouses, and the exchange of goods. Underneath it all, many questions remained—chief among them, what to do if slavery somehow came under threat.

棉花创造了南方的前战争时期。这个利润丰厚的商品使得原本封闭的社会与一个更加宏伟、充满利润、剥削和日益全球化的社会模式连接在了一起。由此,南方与世界都从棉花革命和它激发的城市发展中获益。然而,金光闪闪的背后并不总是黄金。奴隶制依旧存在,并且随着1860年代的临近,内奴隶贸易达到了前所未有的高度。政治、种族关系和奴隶制的沉重负担依旧在汽船的轰鸣声、商号的账房间和商品的交换之下潜伏着。在这一切之下,许多问题依然没有解答,其中最重要的问题是:如果奴隶制遭遇威胁,该如何应对?