第二十三章 大萧条

原标题:The Great Depression

Source / 原文:https://www.americanyawp.com/text/23-the-great-depression

I. Introduction

一、引言

Hard times had hit the United States before, but never had an economic crisis lasted so long or inflicted as much harm as the slump that followed the 1929 crash. After nearly a decade of supposed prosperity, the economy crashed to a halt. People suddenly stopped borrowing and buying. Industries built on debt-fueled purchases sold fewer goods. Retailers lowered prices and, when that did not attract enough buyers to turn profits, they laid off workers to lower labor costs. With so many people out of work and without income, shops sold even less, dropped their prices lower still, and then shed still more workers, creating a vicious downward cycle.

美国历史上曾经历过艰难时期,但从未有一次经济危机像1929年股市崩盘后的萧条那样持续时间长、造成的伤害如此深重。经过近十年的“繁荣”时期,经济突然崩溃。人们不再借贷,也不再消费。依赖债务驱动购买的产业开始销售越来越少的商品。零售商降价促销,但即便如此也未能吸引足够的消费者,无法扭转亏损,最终他们开始裁员以降低劳动力成本。随着越来越多的人失业且没有收入,商店的销量进一步下降,价格再次下调,随之而来的是更多的裁员,形成了一个恶性循环。

Four years after the crash, the Great Depression reached its lowest point: nearly one in four Americans who wanted a job could not find one and, of those who could, more than half had to settle for part-time work. Farmers could not make enough money from their crops to make harvesting worthwhile. Food rotted in the fields of a starving nation.

股市崩盘四年后,大萧条达到了最严重的时刻:几乎四分之一的美国人找不到工作,而那些找到工作的,超过一半的人只能做兼职工作。农民从农作物中获得的收入不足以弥补收割成本,食物在饥荒的土地上腐烂。

The needy drew down whatever savings they had, turned to their families, and sought out charities for public assistance. Soon they all were depleted. Unemployed workers and cash-strapped farmers defaulted on their debts, including mortgages. Already over-extended banks, deprived of income, took savings accounts down with them when they closed. Fear-stricken observers went to their own banks and demanded their deposits. Banks that otherwise might have endured the crisis fell prey to panic, and shut down as well.

贫困家庭用尽了所有积蓄,依赖亲朋,寻求慈善机构的帮助。但这些资源很快也耗尽。失业工人和陷入困境的农民无法偿还债务,包括抵押贷款。那些已经过度扩张的银行因收入枯竭倒闭,储蓄账户也随之一同消失。恐慌的民众蜂拥到银行要求提取存款。那些本可能挺过危机的银行也在恐慌中倒闭了。

With so little being bought and sold, and so little lent and spent, with even bankers unable to lay their hands on money, the nation’s economy ground nearly to a halt. None of the remedies adopted by the president or the Congress succeeded—not higher tariffs, nor restriction of immigration, nor sticking to sound money, nor expressions of confidence in the resilience of the American people. Whatever good these measures achieved, it was not enough.

在如此低迷的消费和投资环境下,甚至连银行家也无法获取资金,国家经济几乎完全停滞。总统和国会采取的所有措施都未能成功——无论是提高关税、限制移民、坚持金本位,还是表达对美国人民韧性的信心。这些措施虽然有所成效,但远不足以扭转局势。

In the 1932 presidential election, the incumbent president, Herbert Hoover, a Republican, promised that he would stand firm against those who, he said, would destroy the U.S. Constitution to restore the economy. Chief among these supposedly dangerous experimenters was the Democratic presidential nominee, New York governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, who began his campaign by pledging a New Deal for the American people.

在1932年的总统选举中,现任总统赫伯特·胡佛(Herbert Hoover)——一位共和党人——承诺会坚决反对那些他所称的“试图摧毁美国宪法以恢复经济”的人。最主要的所谓“危险实验者”是民主党总统候选人、纽约州州长富兰克林·D·罗斯福(Franklin D. Roosevelt)。罗斯福以提出“新政”作为竞选承诺,来挽救美国人民。

The voters chose Roosevelt in a landslide, inaugurating a rapid and enduring transformation in the U.S. government. Even though the New Deal never achieved as much as its proponents hoped or its opponents feared, it did more than any other peacetime program to change how Americans saw their country.

选民们以压倒性的支持选择了罗斯福,启动了美国政府的迅速而深远的转型。尽管新政未能完全达到其支持者的期望,也未如反对者所担忧的那样彻底,但它比任何其他和平时期的计划都更彻底地改变了美国人对自己国家的认知。

II. The Origins of the Great Depression

二、大萧条的起源

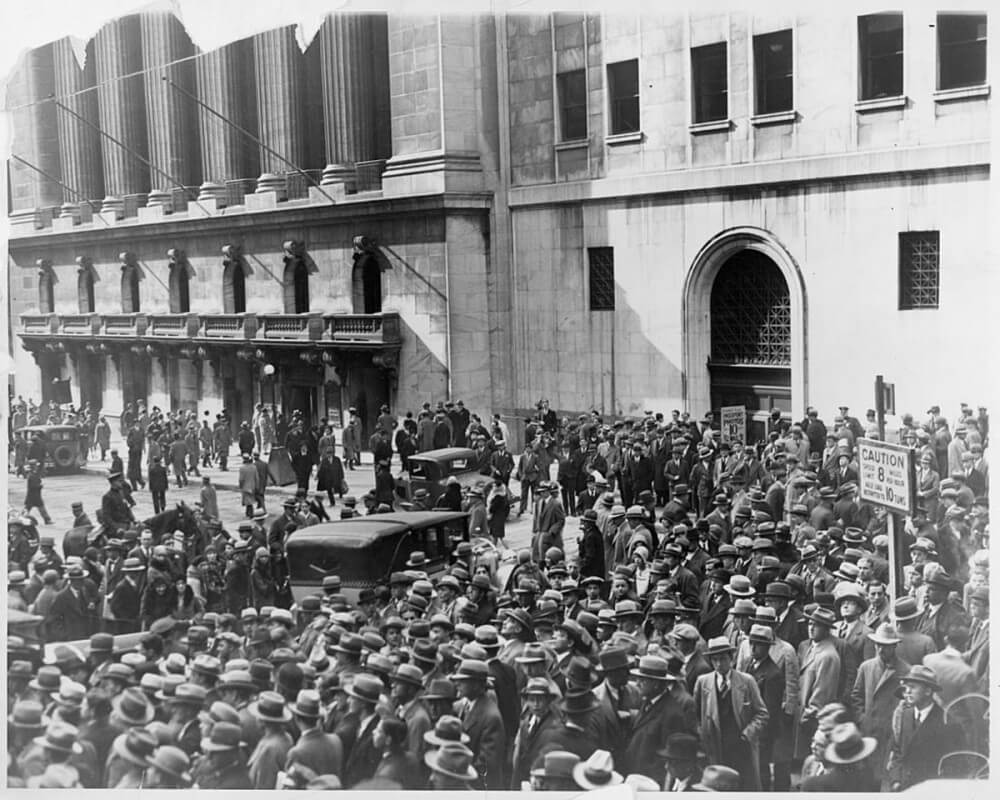

On Thursday, October 24, 1929, stock market prices suddenly plummeted. Ten billion dollars in investments (roughly equivalent to about $100 billion today) disappeared in a matter of hours. Panicked selling set in, stock values sank to sudden lows, and stunned investors crowded the New York Stock Exchange demanding answers. Leading bankers met privately at the offices of J. P. Morgan and raised millions in personal and institutional contributions to halt the slide. They marched across the street and ceremoniously bought stocks at inflated prices. The market temporarily stabilized but fears spread over the weekend and the following week frightened investors dumped their portfolios to avoid further losses. On October 29, Black Tuesday, the stock market began its long precipitous fall. Stock values evaporated. Shares of U.S. Steel dropped from $262 to $22. General Motors stock fell from $73 a share to $8. Four fifths of J. D. Rockefeller’s fortune—the greatest in American history—vanished.

1929年10月24日,星期四,股市价格突然暴跌。不到几个小时,约100亿美元的投资(相当于今天的约1000亿美元)瞬间蒸发。恐慌性抛售席卷而来,股票价值急剧下跌,震惊的投资者纷纷涌向纽约证券交易所要求解释。领先的银行家们在摩根大通的办公室里私下会面,筹集了数百万美元的个人和机构捐款,以阻止股市下跌。他们走到街对面,庄重地以虚高的价格购买股票。股市短暂稳定,但恐惧蔓延,接下来的周末和一周,害怕损失的投资者纷纷抛售股票,清空投资组合。10月29日,所谓“黑色星期二”,股市开始了长时间的急剧下跌。股市的价值几乎蒸发殆尽。美国钢铁公司的股价从262美元跌至22美元。通用汽车的股价从73美元跌至8美元。J.D.洛克菲勒的财富——美国历史上最为庞大的财富——蒸发了四分之三。

Although the crash stunned the nation, it exposed the deeper, underlying problems with the American economy in the 1920s. The stock market’s popularity grew throughout the decade, but only 2.5 percent of Americans had brokerage accounts; the overwhelming majority of Americans had no direct personal stake in Wall Street. The stock market’s collapse, no matter how dramatic, did not by itself depress the American economy. Instead, the crash exposed a great number of factors that, when combined with the financial panic, sank the American economy into the greatest of all economic crises. Rising inequality, declining demand, rural collapse, overextended investors, and the bursting of speculative bubbles all conspired to plunge the nation into the Great Depression.

尽管股市崩盘令全国震惊,但它揭示了20世纪20年代美国经济更深层次的根本问题。股市的受欢迎程度在整个十年里不断增长,但只有2.5%的美国人拥有证券账户;绝大多数美国人并未直接参与华尔街。股市崩盘本身,并没有直接导致美国经济萎缩。相反,崩盘揭示了许多因素,这些因素与金融恐慌交织在一起,共同导致美国经济陷入了历史上最严重的经济危机。日益加剧的不平等、需求下降、农村衰退、过度扩张的投资者以及投机泡沫的破裂,所有这些因素共同作用,最终将国家拖入了大萧条。

Despite resistance by Progressives, the vast gap between rich and poor accelerated throughout the early twentieth century. In the aggregate, Americans were better off in 1929 than in 1920. Per capita income had risen 10 percent for all Americans, but 75 percent for the nation’s wealthiest citizens. The return of conservative politics in the 1920s reinforced federal fiscal policies that exacerbated the divide: low corporate and personal taxes, easy credit, and depressed interest rates overwhelmingly favored wealthy investors who, flush with cash, spent their money on luxury goods and speculative investments in the rapidly rising stock market.

尽管进步主义者反对,20世纪初期贫富差距的扩大却加速了。总体而言,1929年时,美国人的生活水平比1920年要好。人均收入增长了10%,但最富有的25%美国人却增长了75%。20世纪20年代保守政治的回归,加剧了贫富分化的联邦财政政策:低税率、宽松的信贷政策和低利率,极大地有利于富有的投资者,他们手头充裕,将资金投入到奢侈品消费和在飞速上涨的股市中进行投机性投资。

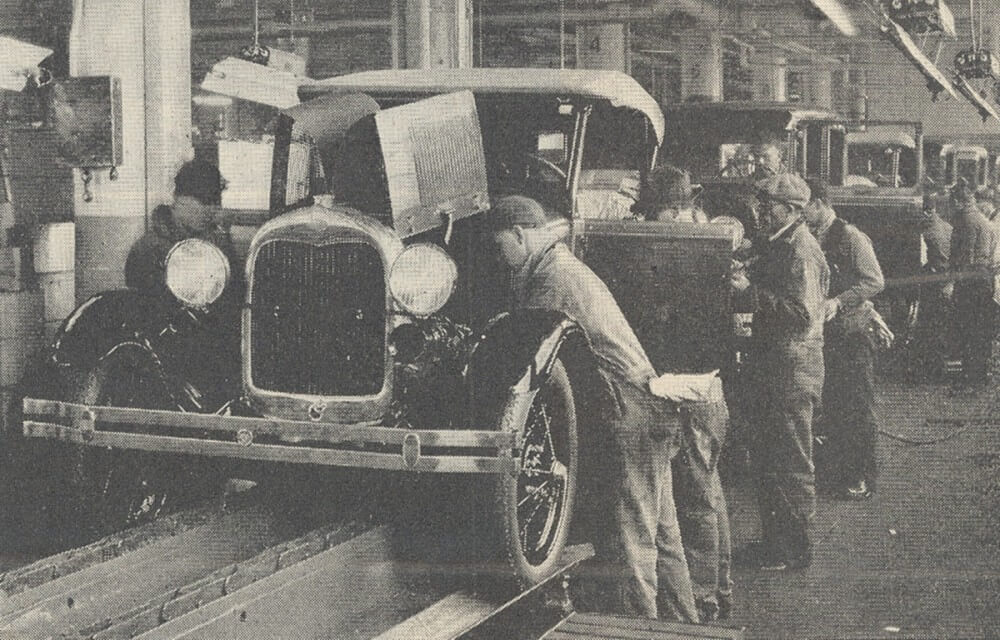

The pro-business policies of the 1920s were designed for an American economy built on the production and consumption of durable goods. Yet by the late 1920s, much of the market was saturated. The boom of automobile manufacturing, the great driver of the American economy in the 1920s, slowed as fewer and fewer Americans with the means to purchase a car had not already done so. More and more, the well-to-do had no need for the new automobiles, radios, and other consumer goods that fueled gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the 1920s. When products failed to sell, inventories piled up, manufacturers scaled back production, and companies fired workers, stripping potential consumers of cash, blunting demand for consumer goods, and replicating the downward economic cycle. The situation was only compounded by increased automation and rising efficiency in American factories. Despite impressive overall growth throughout the 1920s, unemployment hovered around 7 percent throughout the decade, suppressing purchasing power for a great swath of potential consumers.

20世纪20年代的亲商政策,旨在支撑以耐用品生产和消费为支柱的美国经济。然而到1920年代末期,许多市场已经饱和。作为20年代美国经济驱动力的汽车制造业,随着越来越少的美国人具备购买汽车的条件而趋于放缓。越来越多的富裕阶层已经不再需要新的汽车、收音机和其他消费品,这些产品曾是20年代国内生产总值(GDP)增长的推动力。当商品未能销售时,库存积压,制造商减少生产,公司裁员,剥夺了潜在消费者的购买力,抑制了对消费品的需求,并复制了经济的下行循环。随着自动化的增加和美国工厂生产效率的提高,情况变得更加复杂。尽管20年代美国经济总体增长显著,但失业率在整个十年里维持在大约7%左右,这压制了大部分潜在消费者的购买力。

For American farmers, meanwhile, hard times began long before the markets crashed. In 1920 and 1921, after several years of larger-than-average profits, farm prices in the South and West continued their long decline, plummeting as production climbed and domestic and international demand for cotton, foodstuffs, and other agricultural products stalled. Widespread soil exhaustion on western farms only compounded the problem. Farmers found themselves unable to make payments on loans taken out during the good years, and banks in agricultural areas tightened credit in response. By 1929, farm families were overextended, in no shape to make up for declining consumption, and in a precarious economic position even before the Depression wrecked the global economy.

与此同时,对于美国农民来说,艰难的时光早在股市崩盘之前就已经开始。1920年和1921年,在几年的丰厚利润之后,南方和西部的农产品价格继续长期下跌。随着生产的增加以及棉花、食品和其他农产品在国内外的需求停滞,农产品价格急剧下跌。西部农场普遍的土壤疲劳问题使这一局面更加复杂。农民们发现自己无法偿还在繁荣时期借来的贷款,而农业地区的银行也收紧了信贷。到1929年,农场家庭的负担已经过重,无法弥补消费下降的缺口,甚至在大萧条彻底破坏全球经济之前,他们的经济状况就已经岌岌可危。

Despite serious foundational problems in the industrial and agricultural economy, most Americans in 1929 and 1930 still believed the economy would bounce back. In 1930, amid one of the Depression’s many false hopes, President Herbert Hoover reassured an audience that “the depression is over.” But the president was not simply guilty of false optimism. Hoover made many mistakes. During his 1928 election campaign, Hoover promoted higher tariffs as a means for encouraging domestic consumption and protecting American farmers from foreign competition. Spurred by the ongoing agricultural depression, Hoover signed into law the highest tariff in American history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, just as global markets began to crumble. Other countries responded in kind, tariff walls rose across the globe, and international trade ground to a halt. Between 1929 and 1932, international trade dropped from $36 billion to only $12 billion. American exports fell by 78 percent. Combined with overproduction and declining domestic consumption, the tariff exacerbated the world’s economic collapse.

尽管工业和农业经济存在严重的基础性问题,但大多数美国人在1929年和1930年依然相信经济会复苏。1930年,在大萧条带来的一系列虚假的希望中,赫伯特·胡佛总统向听众保证“经济萧条已经结束”。然而,总统并不仅仅是对未来过于乐观。胡佛确实犯了许多错误。在1928年总统竞选中,胡佛推崇提高关税,以此来促进国内消费,并保护美国农民免受外国竞争的冲击。受持续农业萧条的推动,胡佛签署了美国历史上最高的关税法案——《斯穆特-霍利关税法》(Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930),恰逢全球市场开始崩溃之际。其他国家也纷纷采取类似措施,全球范围内关税壁垒增加,国际贸易陷入停滞。1929年至1932年间,国际贸易从360亿美元骤降至120亿美元。美国出口下降了78%。加上生产过剩和国内消费下降,关税政策加剧了全球经济崩溃的局面。

But beyond structural flaws, speculative bubbles, and destructive protectionism, the final contributing element of the Great Depression was a quintessentially human one: panic. The frantic reaction to the market’s fall aggravated the economy’s other many failings. More economic policies backfired. The Federal Reserve overcorrected in their response to speculation by raising interest rates and tightening credit. Across the country, banks denied loans and called in debts. Their patrons, afraid that reactionary policies meant further financial trouble, rushed to withdraw money before institutions could close their doors, ensuring their fate. Such bank runs were not uncommon in the 1920s, but in 1930, with the economy worsening and panic from the crash accelerating, 1,352 banks failed. In 1932, nearly 2,300 banks collapsed, taking personal deposits, savings, and credit with them.

然而,除了结构性缺陷、投机泡沫和破坏性保护主义之外,最终导致大萧条的一个重要因素是典型的人类因素:恐慌。对股市崩盘的惊慌反应加剧了经济中其他许多问题。更多的经济政策适得其反。美联储为应对投机过度调整,提升了利率并收紧了信贷。全国范围内,银行拒绝发放贷款并要求偿还债务。担心反动政策意味着进一步的金融困境,银行客户纷纷提前取款,以防止银行关闭自己的账户,从而确保自己的存款安全。这类银行挤兑在20年代并不罕见,但到了1930年,随着经济状况恶化和股市崩盘带来的恐慌加剧,共有1,352家银行倒闭。到1932年,近2,300家银行倒闭,带走了个人存款、储蓄和信贷。

The Great Depression was the confluence of many problems, most of which had begun during a time of unprecedented economic growth. Fiscal policies of the Republican “business presidents” undoubtedly widened the gap between rich and poor and fostered a standoff over international trade, but such policies were widely popular and, for much of the decade, widely seen as a source of the decade’s explosive growth. With fortunes to be won and standards of living to maintain, few Americans had the foresight or wherewithal to repudiate an age of easy credit, rampant consumerism, and wild speculation. Instead, as the Depression worked its way across the United States, Americans hoped to weather the economic storm as best they could, hoping for some relief from the ever-mounting economic collapse that was strangling so many lives.

大萧条是众多问题交织的结果,其中大部分问题源自一个前所未有的经济增长时期。共和党“商业总统”的财政政策无疑加剧了贫富差距,导致了国际贸易方面的僵局,但这些政策在当时广受欢迎,并且在整个十年中,被视为推动经济爆炸性增长的源泉。在财富可得、生活水平需要维持的情况下,很少有美国人具备拒绝这种“廉价信贷”、“肆意消费”和“疯狂投机”时代的远见或能力。相反,随着大萧条的蔓延,美国人希望尽可能度过这场经济风暴,希望能从日益严重的经济崩溃中获得一些缓解,以摆脱不断压迫无数家庭的困境。

III. Herbert Hoover and the Politics of the Depression

三、赫伯特·胡佛与大萧条政治

As the Depression spread, public blame settled on President Herbert Hoover and the conservative politics of the Republican Party. In 1928, having won the presidency in a landslide, Hoover had no reason to believe that his presidency would be any different than that of his predecessor, Calvin Coolidge, whose time in office was marked by relative government inaction, seemingly rampant prosperity, and high approval ratings. Hoover entered office on a wave of popular support, but by October 1929 the economic collapse had overwhelmed his presidency. Like all too many Americans, Hoover and his advisors assumed—or perhaps simply hoped—that the sharp financial and economic decline was a temporary downturn, another “bust” of the inevitable boom-bust cycles that stretched back through America’s commercial history. “Any lack of confidence in the economic future and the basic strength of business in the United States is simply foolish,” he said in November. And yet the crisis grew. Unemployment commenced a slow, sickening rise. New-car registrations dropped by almost a quarter within a few months. Consumer spending on durable goods dropped by a fifth in 1930.

随着大萧条的蔓延,公众的指责集中到了总统赫伯特·胡佛和共和党的保守政治上。1928年,胡佛在总统选举中取得压倒性胜利,他没有理由认为自己的总统任期会有别于他的前任卡尔文·柯立芝(Calvin Coolidge)的政府——柯立芝任期内政府几乎不作为,似乎经济繁荣一片,民众对政府的满意度也很高。胡佛上任时得到了广泛的民众支持,但到1929年10月,经济崩溃已彻底压倒了他的总统任期。像许多美国人一样,胡佛和他的顾问们认为——或者只是抱有希望——这种急剧的金融和经济衰退不过是暂时的经济低谷,是美国商业历史中不断出现的繁荣—萧条循环中的一次“萧条”而已。他在11月曾说:“对美国经济未来和商业基本实力缺乏信心是纯粹愚蠢的。”然而,危机愈发加剧。失业开始缓慢而令人不安地上升。几个月内,新车登记量下降了近四分之一。1930年,消费者对耐用品的支出下降了五分之一。

When suffering Americans looked to Hoover for help, Hoover could only answer with volunteerism. He asked business leaders to promise to maintain investments and employment and encouraged state and local charities to assist those in need. Hoover established the President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief, or POUR, to help organize the efforts of private agencies. While POUR urged charitable giving, charitable relief organizations were overwhelmed by the growing needs of the many multiplying unemployed, underfed, and unhoused Americans. By mid-1932, for instance, a quarter of all of New York’s private charities closed: they had simply run out of money. In Atlanta, solvent relief charities could only provide $1.30 per week to needy families. The size and scope of the Depression overpowered the radically insufficient capacity of private volunteer organizations to mediate the crisis.

当受苦的美国人向胡佛寻求帮助时,胡佛只能用志愿主义来回应。他要求商业领袖承诺保持投资和就业,并鼓励州和地方慈善机构帮助有需要的人。胡佛成立了总统失业救济组织(President’s Organization for Unemployment Relief,简称POUR),以帮助组织私人机构的救助工作。尽管POUR鼓励捐款,但慈善救助组织因应对日益增加的失业、饥饿和无家可归的美国人需求的能力不足而不堪重负。例如,到1932年中期,纽约市四分之一的私人慈善机构关闭了,因为它们的资金已经耗尽。在亚特兰大,一些还算有偿的救济机构只能向需要帮助的家庭提供每周1.30美元的救济。大萧条的规模和范围超过了私人志愿组织应对危机的能力。

Although Hoover is sometimes categorized as a “business president” in line with his Republican predecessors, he also embraced a kind of business progressivism, a system of voluntary action called associationalism that assumed Americans could maintain a web of voluntary cooperative organizations dedicated to providing economic assistance and services to those in need. Businesses, the thinking went, would willingly limit harmful practice for the greater economic good. To Hoover, direct government aid would discourage a healthy work ethic while associationalism would encourage the self-control and self-initiative that fueled economic growth. But when the Depression exposed the incapacity of such strategies to produce an economic recovery, Hoover proved insufficiently flexible to recognize the limits of his ideology. “We cannot legislate ourselves out of a world economic depression,” he told Congress in 1931.

尽管胡佛有时被归类为“商业总统”,与他之前的共和党总统类似,但他也接受了一种“商业进步主义”,即一种名为“联合主义”(associationalism)的志愿行动体系,假设美国人能够维持一个由志愿合作组织构成的网络,致力于为有需要的人提供经济援助和服务。按照这种思路,企业将自愿限制有害的行为以促进整体经济利益。胡佛认为,直接的政府援助会削弱健康的工作伦理,而联合主义则能够鼓励自我控制和自我倡议,这正是经济增长的推动力。然而,当大萧条暴露出这种策略无法促使经济复苏的局限性时,胡佛却未能足够灵活地认识到自己意识形态的局限性。他在1931年告诉国会:“我们无法通过立法走出全球经济萧条。”

Hoover resisted direct action. As the crisis deepened, even bankers and businessmen and the president’s own advisors and appointees all pleaded with him to use the government’s power to fight the Depression. But his conservative ideology wouldn’t allow him to. He believed in limited government as a matter of principle. Senator Robert Wagner of New York said in 1931 that the president’s policy was “to do nothing and when the pressure becomes irresistible to do as little as possible.” By 1932, with the economy long since stagnant and a reelection campaign looming, Hoover, hoping to stimulate American industry, created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to provide emergency loans to banks, building-and-loan societies, railroads, and other private industries. It was radical in its use of direct government aid and out of character for the normally laissez-faire Hoover, but it also bypassed needy Americans to bolster industrial and financial interests. New York congressman Fiorello LaGuardia, who later served as mayor of New York City, captured public sentiment when he denounced the RFC as a “millionaire’s dole.”

胡佛抵制直接干预。随着危机的加深,即便是银行家、商人、总统的顾问和任命人员都纷纷请求他动用政府的权力来应对大萧条。但他的保守主义意识形态不允许他这样做。他坚信有限政府的原则。纽约州参议员罗伯特·瓦格纳(Robert Wagner)在1931年曾说过,总统的政策是:“什么都不做,等到压力变得不可抗拒时,再尽量少做一些。”到1932年,经济早已停滞不前,且连任竞选迫在眉睫,胡佛为了刺激美国工业,创建了重建财政公司(Reconstruction Finance Corporation,简称RFC),为银行、建筑和贷款公司、铁路公司及其他私人企业提供紧急贷款。这是一次极具创新性的直接政府援助,也与一贯倡导自由放任政策的胡佛形象不符,但它并没有直接帮助急需援助的美国人民,而是支持了工业和金融利益。纽约的国会议员菲奥雷洛·拉瓜尔迪亚(Fiorello LaGuardia,后来成为纽约市市长)在公众中广泛传达了民众情绪,指责RFC是“富人的救济”。

IV. The Lived Experience of the Great Depression

In 1934 a woman from Humboldt County, California, wrote to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt seeking a job for her husband, a surveyor, who had been out of work for nearly two years. The pair had survived on the meager income she received from working at the county courthouse. “My salary could keep us going,” she explained, “but—I am to have a baby.” The family needed temporary help, and, she explained, “after that I can go back to work and we can work out our own salvation. But to have this baby come to a home full of worry and despair, with no money for the things it needs, is not fair. It needs and deserves a happy start in life.”

1934年,一位来自加利福尼亚州洪博尔特县的妇女写信给第一夫人埃莉诺·罗斯福,寻求为她的丈夫——一名测量员——找一份工作。丈夫已经失业近两年。这个家庭靠她在县法院工作的微薄收入勉强度日。她解释说:“我的工资足够支撑我们,但——我马上就要生孩子了。”她的家庭需要临时帮助,并且她接着说:“等到孩子出生后,我可以回去工作,我们可以依靠自己的力量度过难关。但是让孩子出生在一个充满忧虑和绝望、没有钱购买所需物品的家中,这是不公平的。孩子需要并且应得一个快乐的开始。”

As the United States slid ever deeper into the Great Depression, such tragic scenes played out time and time again. Individuals, families, and communities faced the painful, frightening, and often bewildering collapse of the economic institutions on which they depended. The more fortunate were spared the worst effects, and a few even profited from it, but by the end of 1932, the crisis had become so deep and so widespread that most Americans had suffered directly. Markets crashed through no fault of their own. Workers were plunged into poverty because of impersonal forces for which they shared no responsibility.

随着美国日益陷入大萧条,这种悲剧性的场景一次又一次地上演。个人、家庭和社区面临着经济机构崩溃的痛苦、恐惧和常常是迷茫的局面。较为幸运的人避开了最严重的影响,甚至有些人从中获益,但到了1932年底,危机已深刻且广泛,几乎所有的美国人都直接遭受了影响。市场崩溃并非他们的过错,工人们由于一些无法控制的、与自己无关的外部力量,陷入了贫困。

With rampant unemployment and declining wages, Americans slashed expenses. The fortunate could survive by simply deferring vacations and regular consumer purchases. Middle- and working-class Americans might rely on disappearing credit at neighborhood stores, default on utility bills, or skip meals. Those who could borrowed from relatives or took in boarders in homes or “doubled up” in tenements. But such resources couldn’t withstand the unending relentlessness of the economic crisis. As one New York City official explained in 1932,

在普遍失业和工资下降的情况下,美国人削减开支。幸运的人通过简单地推迟度假和常规消费来维持生活。中产阶级和工薪阶层可能依赖于邻里商店不再提供的信用,拖欠水电费,或跳过一餐。有些人则向亲戚借钱,或收养寄宿生、将家中空间“合并”以降低开销。但这些资源经不起经济危机持续不断的冲击。正如一位纽约市官员在1932年所解释的:

When the breadwinner is out of a job he usually exhausts his savings if he has any.… He borrows from his friends and from his relatives until they can stand the burden no longer. He gets credit from the corner grocery store and the butcher shop, and the landlord forgoes collecting the rent until interest and taxes have to be paid and something has to be done. All of these resources are finally exhausted over a period of time, and it becomes necessary for these people, who have never before been in want, to go on assistance.

“当养家糊口的人失业时,他通常会把自己的积蓄花光……他从朋友和亲戚那里借钱,直到他们也无法承受这种负担。他会在街角的杂货店和肉铺借到赊账,房东会暂时不收租金,直到利息和税款到期,必须采取措施。所有这些资源最终都在一段时间后耗尽,这些从未曾贫困过的人就不得不去寻求救济。”

But public assistance and private charities were quickly exhausted by the scope of the crisis. As one Detroit city official put it in 1932,

然而,公共援助和私人慈善机构很快就被危机的规模压垮了。正如一位底特律市官员在1932年所说:

Many essential public services have been reduced beyond the minimum point absolutely essential to the health and safety of the city.… The salaries of city employees have been twice reduced … and hundreds of faithful employees … have been furloughed. Thus has the city borrowed from its own future welfare to keep its unemployed on the barest subsistence levels.… A wage work plan which had supported 11,000 families collapsed last month because the city was unable to find funds to pay these unemployed—men who wished to earn their own support. For the coming year, Detroit can see no possibility of preventing wide-spread hunger and slow starvation through its own unaided resources.

“许多基本的公共服务已经被削减到最低限度,基本保障了城市的健康和安全……城市员工的薪水已被削减两次……数百名忠诚的员工……已被暂时解雇。这样,城市为保持失业者的基本生活水平,借用了自己未来的福利……支持11,000个家庭的工资工作计划上个月已经崩溃,因为城市无法筹措资金支付这些失业者——这些希望自食其力的人。对于即将到来的这一年,底特律无法看到通过自己的力量防止广泛的饥饿和慢性饥荒的可能。”

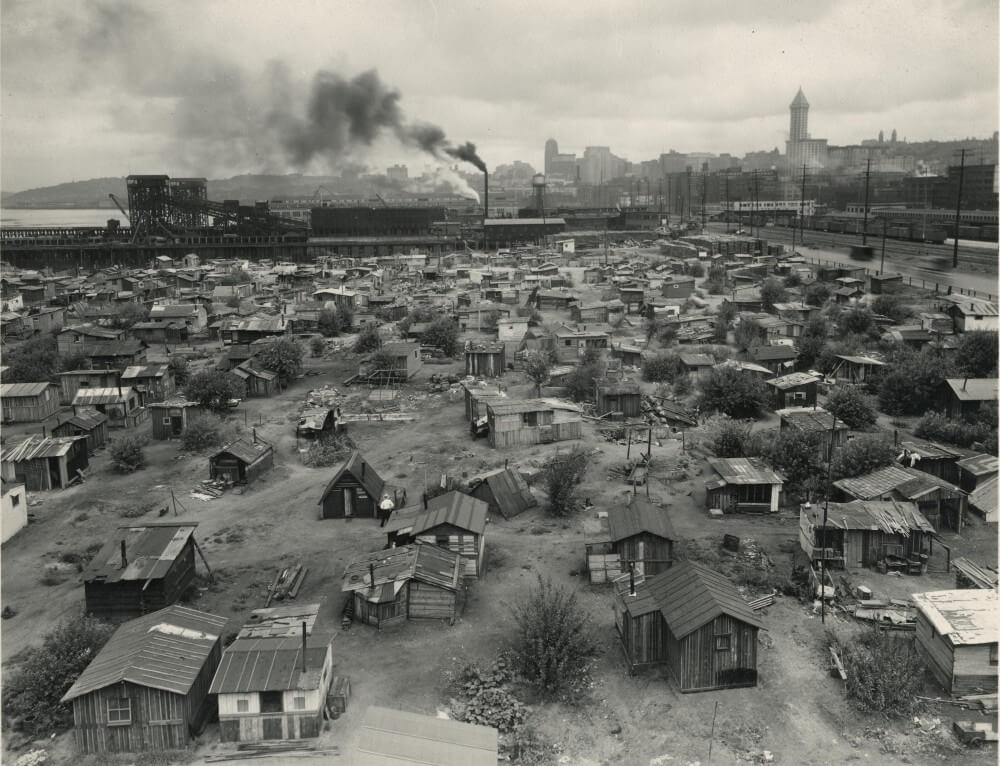

These most desperate Americans, the chronically unemployed, encamped on public or marginal lands in “Hoovervilles,” spontaneous shantytowns that dotted America’s cities, depending on bread lines and street-corner peddling. One doctor recalled that “every day … someone would faint on a streetcar. They’d bring him in, and they wouldn’t ask any questions.… they knew what it was. Hunger.” “A man is not a man without work,” one of the jobless told an interviewer. The ideal of the “male breadwinner” was always a fiction for poor Americans, and, during the crisis, women and young children entered the labor force, as they always had. But, in such a labor crisis, many employers, subscribing to traditional notions of male bread-winning, were less likely to hire married women and more likely to dismiss those they already employed. As one politician remarked at the time, the woman worker was “the first orphan in the storm.”

这些最为绝望的美国人——长期失业者,露宿街头或在公共土地、边缘地区建立“胡佛村”的流浪者——依靠面包线和街头叫卖为生。一位医生回忆说:“每天……总有人在电车上晕倒。我们把他们带进来,他们不会问任何问题……他们知道那是什么——饥饿。”一位失业者告诉采访者:“一个人没有工作就不是一个人。”对于贫困的美国人来说,男性养家糊口的理想始终是虚构的,在这场危机中,女性和儿童进入劳动力市场,如同往常一样。但在如此严重的劳动危机中,许多雇主坚持传统的男性养家糊口观念,因此他们更不愿雇佣已婚女性,甚至会解雇已雇佣的已婚女性。正如当时一位政治人物所言,女性工人是“风暴中的第一位孤儿”。

American suppositions about family structure meant that women suffered disproportionately from the Depression. Since the start of the twentieth century, single women had become an increasing share of the workforce, but married women, Americans were likely to believe, took a job because they wanted to and not because they needed it. Once the Depression came, employers were therefore less likely to hire married women and more likely to dismiss those they already employed. Women on their own and without regular work suffered a greater threat of sexual violence than their male counterparts; accounts of such women suggest they depended on each other for protection.

美国人对家庭结构的假设意味着,女性在大萧条中的遭遇尤为艰难。自20世纪初以来,单身女性逐渐成为劳动力的一部分,但美国人普遍认为,已婚女性工作是因为她们愿意,而不是因为她们需要工作。一旦大萧条来临,雇主因此不愿雇佣已婚女性,甚至会解雇已经聘用的已婚女性。没有正式工作的单身女性面临的性暴力威胁比男性更为严重;关于这些女性的记载表明,她们相互依靠来获得保护。

The Great Depression was particularly tough for nonwhite Americans. “The Negro was born in depression,” one Black pensioner told interviewer Studs Terkel. “It didn’t mean too much to him. The Great American Depression . . . only became official when it hit the white man.” Black workers were generally the last hired when businesses expanded production and the first fired when businesses experienced downturns. As a National Urban League study found, “So general is this practice that one is warranted in suspecting that it has been adopted as a method of relieving unemployment of whites without regard to the consequences upon Negroes.” In 1932, with the national unemployment average hovering around 25 percent, Black unemployment reached as high as 50 percent, while even Black workers who kept their jobs saw their already low wages cut dramatically.

对于非白人美国人来说,大萧条特别艰难。“黑人天生就是生活在萧条中的,”一位黑色退休人员告诉访谈者斯图兹·特克尔。“这对他来说没什么意义。大萧条……只有当它波及到白人时,才成了官方的萧条。”黑人工人通常是企业扩张时最后被雇佣的人,而在经济衰退时则是首先被解雇的。正如国家城市联盟的一项研究所发现,“这种做法已经如此普遍,以至于人们有理由怀疑,它已经成为了一种通过不顾后果地解救白人失业的方式。”1932年,随着全国失业率接近25%,黑人失业率高达50%,即使是保住工作的黑人,其原本低廉的工资也遭到了大幅削减。

V. Migration and the Great Depression

On the Great Plains, environmental catastrophe deepened America’s longstanding agricultural crisis and magnified the tragedy of the Depression. Beginning in 1932, severe droughts hit from Texas to the Dakotas and lasted until at least 1936. The droughts compounded years of agricultural mismanagement. To grow their crops, Plains farmers had plowed up natural ground cover that had taken ages to form over the surface of the dry Plains states. Relatively wet decades had protected them, but, during the early 1930s, without rain, the exposed fertile topsoil turned to dust, and without sod or windbreaks such as trees, rolling winds churned the dust into massive storms that blotted out the sky, choked settlers and livestock, and rained dirt not only across the region but as far east as Washington, D.C., New England, and ships on the Atlantic Ocean. The Dust Bowl, as the region became known, exposed all-too-late the need for conservation. The region’s farmers, already hit by years of foreclosures and declining commodity prices, were decimated. For many in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas who were “baked out, blown out, and broke,” their only hope was to travel west to California, whose rains still brought bountiful harvests and—potentially—jobs for farmworkers. It was an exodus. Oklahoma lost 440,000 people, or a full 18.4 percent of its 1930 population, to outmigration.

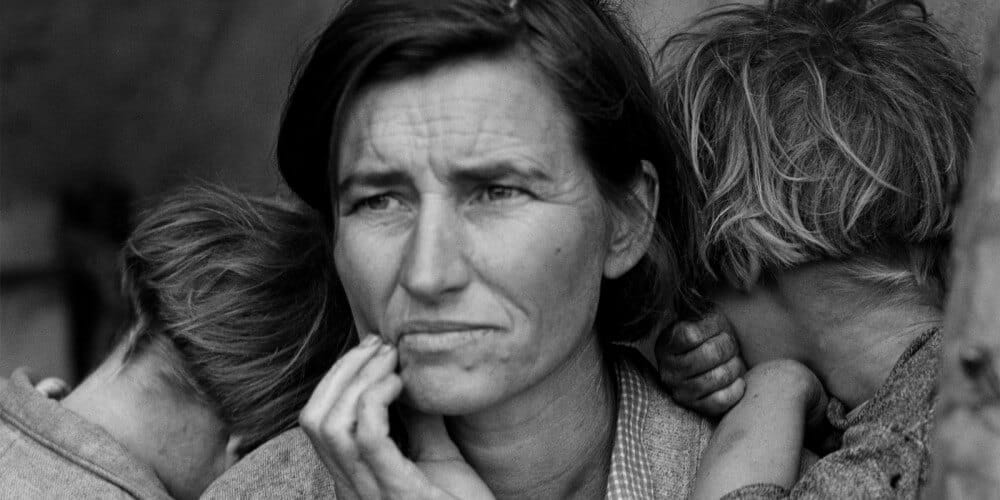

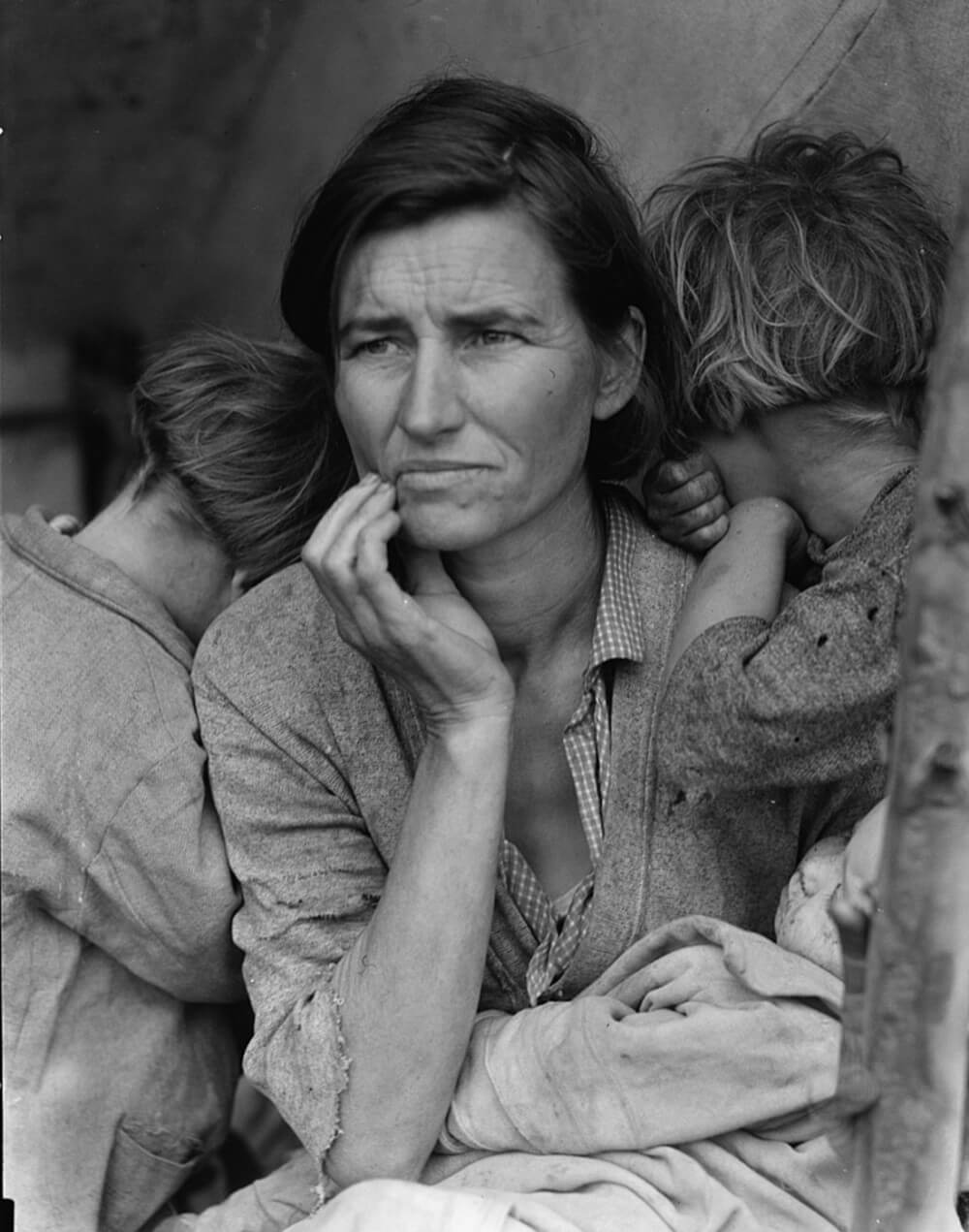

Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother became one of the most enduring images of the Dust Bowl and the ensuing westward exodus. Lange, a photographer for the Farm Security Administration, captured the image at a migrant farmworker camp in Nipomo, California, in 1936. In the photograph a young mother stares out with a worried, weary expression. She was a migrant, having left her home in Oklahoma to follow the crops to the Golden State. She took part in what many in the mid-1930s were beginning to recognize as a vast migration of families out of the southwestern Plains states. In the image she cradles an infant and supports two older children, who cling to her. Lange’s photo encapsulated the nation’s struggle. The subject of the photograph seemed used to hard work but down on her luck, and uncertain about what the future might hold.

The Okies, as such westward migrants were disparagingly called by their new neighbors, were the most visible group who were on the move during the Depression, lured by news and rumors of jobs in far-flung regions of the country. Men from all over the country, some abandoning families, hitched rides, hopped freight cars, or otherwise made their way around the country. By 1932, sociologists were estimating that millions of men were on the roads and rails traveling the country. Popular magazines and newspapers were filled with stories of homeless boys and the veterans-turned-migrants of the Bonus Army commandeering boxcars. Popular culture, such as William Wellman’s 1933 film, Wild Boys of the Road, and, most famously, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, published in 1939 and turned into a hit movie a year later, captured the Depression’s dislocated populations.

These years witnessed the first significant reversal in the flow of people between rural and urban areas. Thousands of city dwellers fled the jobless cities and moved to the country looking for work. As relief efforts floundered, many state and local officials threw up barriers to migration, making it difficult for newcomers to receive relief or find work. Some state legislatures made it a crime to bring poor migrants into the state and allowed local officials to deport migrants to neighboring states. In the winter of 1935–1936, California, Florida, and Colorado established “border blockades” to block poor migrants from their states and reduce competition with local residents for jobs. A billboard outside Tulsa, Oklahoma, informed potential migrants that there were “NO JOBS in California” and warned them to “KEEP Out.”

Sympathy for migrants, however, accelerated late in the Depression with the publication of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The Joad family’s struggles drew attention to the plight of Depression-era migrants and, just a month after the nationwide release of the film version, Congress created the Select Committee to Investigate the Interstate Migration of Destitute Citizens. Starting in 1940, the committee held widely publicized hearings. But it was too late. Within a year of its founding, defense industries were already gearing up in the wake of the outbreak of World War II, and the “problem” of migration suddenly became a lack of migrants needed to fill war industries. Such relief was nowhere to be found in the 1930s.

Americans meanwhile feared foreign workers willing to work for even lower wages. The Saturday Evening Post warned that foreign immigrants, who were “compelled to accept employment on any terms and conditions offered,” would exacerbate the economic crisis. On September 8, 1930, the Hoover administration issued a press release on the administration of immigration laws “under existing conditions of unemployment.” Hoover instructed consular officers to scrutinize carefully the visa applications of those “likely to become public charges” and suggested that this might include denying visas to most, if not all, alien laborers and artisans. The crisis itself had stifled foreign immigration, but such restrictive and exclusionary actions in the first years of the Depression intensified its effects. The number of European visas issued fell roughly 60 percent while deportations dramatically increased. Between 1930 and 1932, fifty-four thousand people were deported. An additional forty-four thousand deportable aliens left “voluntarily.”

Exclusionary measures hit Mexican immigrants particularly hard. The State Department made a concerted effort to reduce immigration from Mexico as early as 1929, and Hoover’s executive actions arrived the following year. Officials in the Southwest led a coordinated effort to push out Mexican immigrants. In Los Angeles, the Citizens Committee on Coordination of Unemployment Relief began working closely with federal officials in early 1931 to conduct deportation raids, while the Los Angeles County Department of Charities began a simultaneous drive to repatriate Mexicans and Mexican Americans on relief, negotiating a charity rate with the railroads to return Mexicans “voluntarily” to their mother country. According to the federal census, from 1930 to 1940 the Mexican-born population living in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas fell from 616,998 to 377,433. Franklin Roosevelt did not indulge anti-immigrant sentiment as willingly as Hoover had. Under the New Deal, the Immigration and Naturalization Service halted some of the Hoover administration’s most divisive practices, but with jobs suddenly scarce, hostile attitudes intensified, and official policies less than welcoming, immigration plummeted and deportations rose. Over the course of the Depression, more people left the United States than entered it.

VI. The Bonus Army

六、优抚军(Bonus Army)

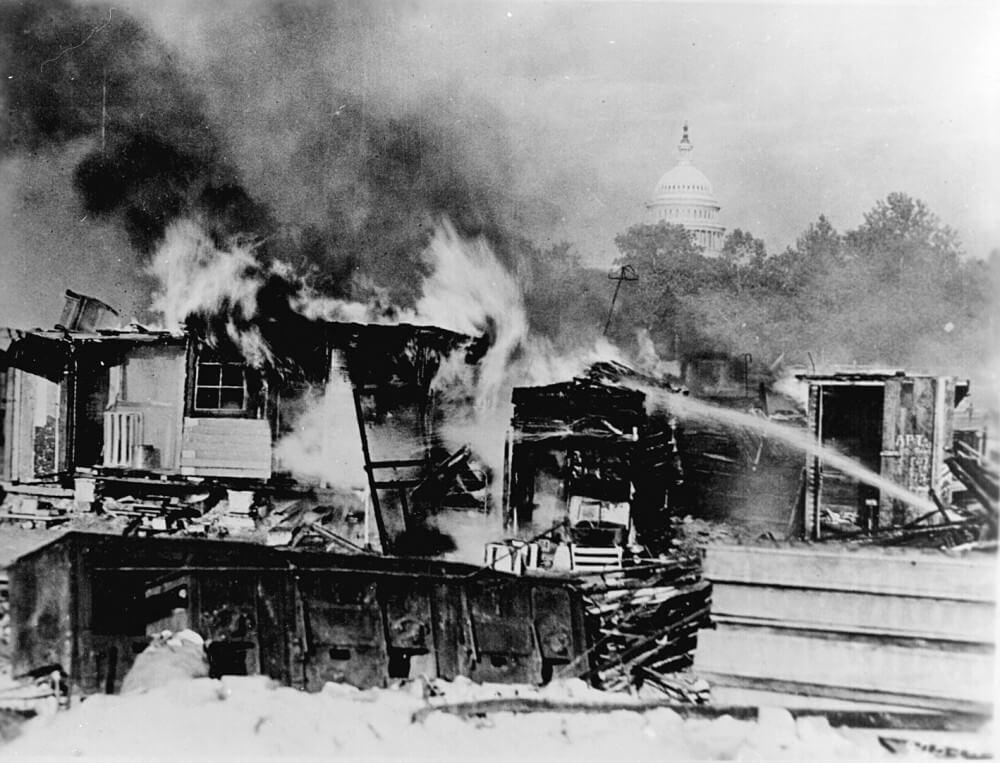

In the summer of 1932, more than fifteen-thousand unemployed veterans and their families converged on Washington, D.C. to petition for a bill authorizing immediate payment of cash bonuses to veterans of World War I that were originally scheduled to be paid out in 1945. Given the economic hardships facing the country, the bonus came to symbolize government relief for the most deserving recipients. The veterans in D.C. erected a tent city across the Potomac River in Anacostia Flats, a “Hooverville” in the spirit of the camps of homeless and unemployed Americans then appearing in American cities. Calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or the Bonus Army, they drilled and marched and demonstrated for their bonuses. “While there were billions for bankers, there was nothing for the poor,” they complained.

1932年夏季,超过一万五千名失业的退伍军人及其家属汇聚到华盛顿特区,要求通过一项法案,立即支付第一次世界大战退伍军人本应于1945年支付的现金奖励。鉴于国家面临的经济困境,这项奖金成为政府对最应得受益者提供援助的象征。这些退伍军人在人口稠密的安那科斯提亚平原上搭建了帐篷城市,这是一个类似于美国城市中流浪者和失业者所建立的“胡佛村”。他们自称“优抚远征军”,或称“优抚军”,并进行操练、行进和示威,要求发放奖金。他们抱怨道:“银行家们得到了数十亿,但穷人却什么都得不到。”

Concerned with what immediate payment would do to the federal budget, Hoover opposed the bill, which was eventually voted down by the Senate. While most of the “Bonus Army” left Washington in defeat, many stayed to press their case. Hoover called the remaining veterans “insurrectionists” and ordered them to leave. When thousands failed to heed the vacation order, General Douglas MacArthur, accompanied by local police, infantry, cavalry, tanks, and a machine gun squadron, stormed the tent city and routed the Bonus Army. Troops chased down men and women, tear-gassed children, and torched the shantytown. Two marchers were shot and killed and a baby was killed by tear gas.

胡佛担心立即支付奖金会对联邦预算产生影响,因此反对这项法案,最终该法案在参议院遭到否决。尽管大部分“优抚军”成员最终败退,离开了华盛顿,但许多人留下来继续争取他们的权利。胡佛称留在华盛顿的退伍军人为“叛乱分子”,并下令他们离开。当成千上万的人未遵守撤离命令时,道格拉斯·麦克阿瑟将军带领地方警察、步兵、骑兵、坦克和一支机枪分队,突袭了这个帐篷城市,驱散了优抚军。军队追赶退伍军人和家属,向儿童投掷催泪瓦斯,并纵火烧毁了贫民区。两名示威者被射杀,一名婴儿因催泪瓦斯中毒致死。

The national media reported on the raid, newsreels showed footage, and Americans recoiled at Hoover’s insensitivity toward suffering Americans. His overall unwillingness to address widespread economic problems and his repeated platitudes about returning prosperity condemned his presidency. Hoover of course was not responsible for the Depression, not personally. But neither he nor his advisors conceived of the enormity of the crisis, a crisis his conservative ideology could neither accommodate nor address. Americans had so far found little relief from Washington. But they were still looking for it.

全国媒体报道了这一突袭事件,新闻片展示了相关画面,许多美国人对胡佛对待遭受困苦的美国人表现出的冷漠反应感到震惊。他对广泛经济问题的无动于衷,以及他反复提到恢复繁荣的空洞言辞,宣判了他总统任期的失败。胡佛当然不能为大萧条负责,他个人并没有造成这一危机。但他和他的顾问们未曾认识到这场危机的巨大规模,而他的保守主义意识形态既无法适应,也无法解决这一问题。美国人迄今为止几乎没有从华盛顿得到任何实质性的救济,但他们依然在寻求帮助。

VII. Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the “First” New Deal

七、富兰克林·德拉诺·罗斯福与“首个”新政

The early years of the Depression were catastrophic. The crisis, far from relenting, deepened each year. Unemployment peaked at 25 percent in 1932. With no end in sight, and with private firms crippled and charities overwhelmed by the crisis, Americans looked to their government as the last barrier against starvation, hopelessness, and perpetual poverty.

大萧条的初期是灾难性的。经济危机不仅没有缓解,反而每年愈加加深。1932年失业率达到25%。没有尽头的前景,私人企业瘫痪,慈善组织因危机而不堪重负,美国人将最后的希望寄托于政府,期望政府能成为抵挡饥饿、绝望和永久贫困的最后屏障。

Few presidential elections in modern American history have been more consequential than that of 1932. The United States was struggling through the third year of the Depression, and exasperated voters overthrew Hoover in a landslide for the Democratic governor of New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Roosevelt came from a privileged background in New York’s Hudson River Valley (his distant cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, became president while Franklin was at Harvard) and embarked on a slow but steady ascent through state and national politics. In 1913, he was appointed assistant secretary of the navy, a position he held during the defense emergency of World War I. In the course of his rise, in the summer of 1921, Roosevelt suffered a sudden bout of lower-body pain and paralysis. He was diagnosed with polio. The disease left him a paraplegic, but, encouraged and assisted by his wife, Eleanor, Roosevelt sought therapeutic treatment and maintained sufficient political connections to reenter politics. In 1928, Roosevelt won election as governor of New York. He oversaw the rise of the Depression and drew from the tradition of American progressivism to address the economic crisis. He explained to the state assembly in 1931, the crisis demanded a government response “not as a matter of charity, but as a matter of social duty.” As governor he established the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA), supplying public work jobs at the prevailing wage and in-kind aid—food, shelter, and clothes—to those unable to afford it. Soon the TERA was providing work and relief to ten percent of the state’s families. Roosevelt relied on many like-minded advisors. Frances Perkins, for example, the commissioner of the state’s labor department, successfully advocated pioneering legislation that enhanced workplace safety and reduced the use of child labor in factories. Perkins later accompanied Roosevelt to Washington and served as the nation’s first female secretary of labor.

美国历史上,很少有像1932年这样的总统选举,具有如此深远的影响。美国正经历大萧条的第三年,愤怒的选民在选举中击败了胡佛,选举出了纽约州州长富兰克林·德拉诺·罗斯福。罗斯福来自纽约哈德逊河谷的一个富裕家庭(他的远房表亲西奥多·罗斯福曾在富兰克林上哈佛时成为总统),并在州级和全国政治中逐步上升。1913年,他被任命为海军助理部长,在第一次世界大战的防务紧急状态中,他担任了这个职务。1921年夏天,罗斯福突然感到下半身剧烈疼痛并出现瘫痪,随后被诊断为小儿麻痹症。疾病使他成了瘫痪者,但在妻子埃莉诺的鼓励和帮助下,罗斯福接受了治疗,并保持了足够的政治联系,重新进入了政界。1928年,罗斯福当选为纽约州州长。他在大萧条中逐步上升,并借鉴美国进步主义的传统来应对经济危机。他在1931年向州议会解释,危机需要政府采取行动,“这不是出于慈善,而是出于社会责任。”作为州长,他建立了临时紧急救助局(TERA),为无法自给自足的人提供公共就业、食品、住所和衣物等援助。不久,TERA为州内10%的家庭提供了工作和救助。罗斯福依靠许多志同道合的顾问,例如州劳工部委员弗朗西丝·帕金斯,她成功推动了具有开创性的立法,改善了工作场所的安全,并减少了工厂中的童工使用。帕金斯后来随罗斯福来到华盛顿,成为美国历史上第一位女性劳工部长。

On July 1, 1932, Roosevelt, the newly designated presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, delivered the first and one of the most famous on-site acceptance speeches in American presidential history. In it, he said, “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people.” Newspaper editors seized on the phrase “new deal,” and it entered the American political lexicon as shorthand for Roosevelt’s program to address the Great Depression.

1932年7月1日,罗斯福,作为民主党新任总统候选人,在美国总统历史上发表了首次也是最著名的现场接受演讲之一。在演讲中,他说:“我向你们保证,我向自己保证,为美国人民提供一项新的交易。”报纸编辑们迅速捕捉到“新交易”这一短语,它成为罗斯福用以应对大萧条的计划的代名词。

Roosevelt proposed jobs programs, public work projects, higher wages, shorter hours, old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, farm subsidies, banking regulations, and lower tariffs. Hoover warned that such a program represented “the total abandonment of every principle upon which this government and the American system is founded.” He warned that it reeked of European communism, and that “the so called new deals would destroy the very foundations of the American system of life.”Americans didn’t buy it. Roosevelt crushed Hoover in November. He won more counties than any previous candidate in American history. He spent the months between his election and inauguration–the twentieth amendment, ratified in 1933, would subsequently move the inauguration from March 4 to January 20–traveling, planning, and assembling a team of advisors, the famous Brain Trust of academics and experts, to help him formulate a plan of attack. On March 4, 1933, in his first inaugural address, Roosevelt famously declared, “This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

罗斯福提出了工作计划、公共工程项目、更高的工资、更短的工作时间、养老金、失业保险、农业补贴、银行监管和降低关税等政策。胡佛警告说,这样的计划代表了“完全放弃了这个政府和美国体系所有的原则。”他警告说,这带有欧洲共产主义的气息,并且“所谓的新交易将摧毁美国制度的根基。”但美国人并不接受这一说法。罗斯福在11月的选举中击败了胡佛,赢得了比历史上任何候选人更多的县份。罗斯福在当选和就职之间的几个月里——第20修正案于1933年获得批准,将总统就职日期从3月4日提前到1月20日——进行了旅行、规划,并召集了一支由学者和专家组成的顾问团队,即著名的“大脑信托”,帮助他制定攻击计划。1933年3月4日,在罗斯福的首次就职演讲中,他著名地宣称:“这个伟大的国家将像过去那样挺过来,将复兴并繁荣。因此,首先让我坚信:我们唯一需要恐惧的就是恐惧本身——那种无名的、无理性的、没有根据的恐惧,它使得将撤退转化为进步的努力无法进行。”

Roosevelt’s reassuring words would have rung hollow if he had not taken swift action against the economic crisis. In his first days in office, Roosevelt and his advisors prepared, submitted, and secured congressional enactment of numerous laws designed to arrest the worst of the Great Depression. His administration threw the federal government headlong into the fight against the Depression.Roosevelt immediately looked to stabilize the collapsing banking system. Two out of every five banks open in 1929 had been shuttered and some Federal Reserve banks were on the verge of insolvency. Roosevelt declared a national “bank holiday” closing American banks and set to work pushing the Emergency Banking Act swiftly through Congress. On March 12, the night before select banks reopened under stricter federal guidelines, Roosevelt appeared on the radio in the first of his Fireside Chats. The addresses, which the president continued delivering through four terms, were informal, even personal. Roosevelt used his airtime to explain New Deal legislation, to encourage confidence in government action, and to mobilize the American people’s support. In the first chat, Roosevelt described the new banking safeguards and asked the public to place their trust and their savings in banks. Americans responded and deposits outpaced withdrawals across the country. The act was a major success. In June, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Banking Act, which instituted a federal deposit insurance system through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and barred the mixing of commercial and investment banking.

如果罗斯福没有迅速采取行动应对经济危机,他安慰的话语可能就显得空洞无力了。在上任的第一天,罗斯福和他的顾问们迅速制定并提交了多项法律,以应对大萧条的最严峻部分。他的政府全力投入到抗击经济危机的斗争中。罗斯福立即着手稳定即将崩溃的银行系统。1929年开设的银行中,每五家中就有两家倒闭,一些联邦储备银行几乎破产。罗斯福宣布全国“银行假期”,关闭了美国的银行,并迅速推动《紧急银行法案》通过国会。3月12日,在选定的银行在更严格的联邦指导下重新开门前一晚,罗斯福通过广播进行了首次的“炉边谈话”。这些谈话非正式且具有个人色彩,罗斯福利用广播时间向公众解释新政立法,鼓励人们对政府行动产生信心,并动员美国人民的支持。在第一次炉边谈话中,罗斯福介绍了新的银行保障措施,并请公众把他们的信任和储蓄交给银行。美国人响应了这一号召,存款的数量超过了取款。该法案取得了巨大成功。6月,国会通过了《格拉斯-斯蒂格尔银行法案》,通过联邦存款保险公司(FDIC)建立了联邦存款保险制度,并禁止商业银行和投资银行混合经营。

Stabilizing the banks was only a first step. In the remainder of his First Hundred Days, Roosevelt and his congressional allies focused especially on relief for suffering Americans. Congress debated, amended, and passed what Roosevelt proposed. As one historian noted, the president “directed the entire operation like a seasoned field general.” And despite some questions over the constitutionality of many of his actions, Americans and their congressional representatives conceded that the crisis demanded swift and immediate action. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) employed young men on conservation and reforestation projects; the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) provided direct cash assistance to state relief agencies struggling to care for the unemployed; the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built a series of hydroelectric dams along the Tennessee River as part of a comprehensive program to economically develop a chronically depressed region; and several agencies helped home and farm owners refinance their mortgages. And Roosevelt wasn’t done.

稳定银行系统只是第一步。在接下来的“首个百天”里,罗斯福和他的国会盟友特别专注于对遭受困苦的美国人提供援助。国会辩论、修订并通过了罗斯福提出的议案。正如一位历史学家所指出的,罗斯福“像一位经验丰富的野战指挥官一样指挥着整个行动”。尽管对于许多行动的合宪性存在一些疑问,但美国人和他们的国会议员承认,这场危机需要迅速而即时的行动。民间保护队(CCC)让年轻人参与保护和重新造林项目;联邦紧急救济局(FERA)为各州的救济机构提供直接现金援助,帮助它们照顾失业者;田纳西河流域管理局(TVA)在田纳西河沿线建设了一系列水电大坝,作为一个综合项目来经济开发一个长期贫困的地区;多个机构帮助房主和农场主重新融资贷款。罗斯福并没有止步于此。

The heart of Roosevelt’s early recovery program consisted of two massive efforts to stabilize and coordinate the American economy: the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) and the National Recovery Administration (NRA). The AAA, created in May 1933, aimed to raise the prices of agricultural commodities (and hence farmers’ income) by offering cash incentives to voluntarily limit farm production (decreasing supply, thereby raising prices). The National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), which created the NRA in June 1933, suspended antitrust laws to allow businesses to establish “codes” that would coordinate prices, regulate production levels, and establish conditions of employment to curtail “cutthroat competition.” In exchange for these exemptions, businesses agreed to provide reasonable wages and hours, end child labor, and allow workers the right to unionize. Participating businesses earned the right to display a placard with the NRA’s Blue Eagle, showing their cooperation in the effort to combat the Great Depression.

罗斯福早期复苏计划的核心由两项巨大努力组成,旨在稳定和协调美国经济:农业调整局(AAA)和国家复兴局(NRA)。农业调整局成立于1933年5月,旨在通过提供现金奖励鼓励农民自愿减少生产(从而减少供给,抬高价格),以提高农业商品的价格和农民的收入。1933年6月通过的《国家工业复兴法》(NIRA)创建了国家复兴局(NRA),暂停反托拉斯法,允许企业建立“行业规范”,以协调价格、生产水平并规定雇佣条件,防止“恶性竞争”。作为交换,参与的企业同意提供合理的工资和工时,终止童工,并允许工人组建工会。参与的企业获得了展示NRA蓝鹰标志的权利,表明它们参与了抗击大萧条的努力。

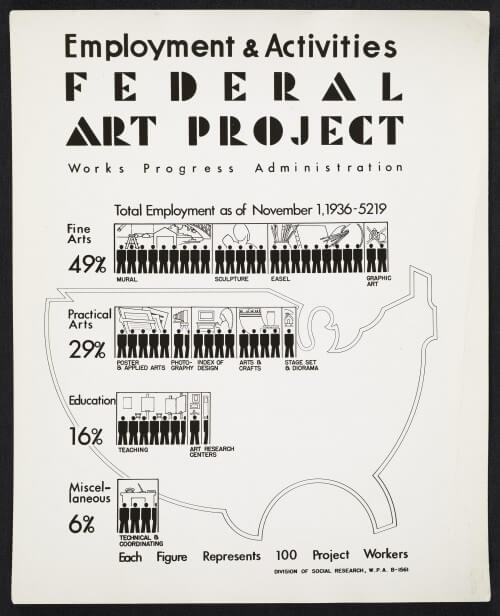

The programs of the First Hundred Days stabilized the American economy and ushered in a robust though imperfect recovery. GDP climbed once more, but even as output increased, unemployment remained stubbornly high. Though the unemployment rate dipped from its high in 1933, when Roosevelt was inaugurated, vast numbers remained out of work. If the economy could not put people back to work, the New Deal would try. The Civil Works Administration (CWA) and, later, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) put unemployed men and women to work on projects designed and proposed by local governments. The Public Works Administration (PWA) provided grants-in-aid to local governments for large infrastructure projects, such as bridges, tunnels, schoolhouses, libraries, and America’s first federal public housing projects. Together, they provided not only tangible projects of immense public good but employment for millions. The New Deal was reshaping much of the nation.

“首个百天”的政策稳定了美国经济,开启了强劲但不完美的复苏。国内生产总值再次增长,但即使产出增加,失业率仍顽固地居高不下。虽然1933年罗斯福就职时的失业率有所下降,但大量人们依然处于失业状态。如果经济无法帮助人们找到工作,那么新政就要尝试做到这一点。民间工程管理局(CWA)和后来的公共事业进步管理局(WPA)将失业的男女派往由地方政府设计和提议的项目上工作。公共工程管理局(PWA)为地方政府的大型基础设施项目(如桥梁、隧道、学校、图书馆以及美国首批联邦公共住房项目)提供资助。它们不仅提供了巨大的公共利益项目,还为数百万美国人提供了就业机会。新政正在重塑整个国家。

VIII. The New Deal in the South

八、新政在南方

The impact of initial New Deal legislation was readily apparent in the South, a region of perpetual poverty especially plagued by the Depression. In 1929 the average per capita income in the American Southeast was $365, the lowest in the nation. Southern farmers averaged $183 per year at a time when farmers on the West Coast made more than four times that. Moreover, they were trapped into the production of cotton and corn, crops that depleted the soil and returned ever-diminishing profits. Despite the ceaseless efforts of civic boosters, what little industry the South had remained low-wage, low-skilled, and primarily extractive. Southern workers made significantly less than their national counterparts: 75 percent of nonsouthern textile workers, 60 percent of iron and steel workers, and a paltry 45 percent of lumber workers. At the time of the crash, southerners were already underpaid, underfed, and undereducated.

最初的新政立法对南方的影响显而易见,南方是一个常年贫困、尤其受大萧条困扰的地区。1929年,美国东南部的人均收入为365美元,是全国最低的。南方农民的年均收入为183美元,而西海岸的农民收入是他们的四倍以上。此外,南方农民陷入了棉花和玉米的生产中,这些作物不仅耗尽了土地,还带来了日益减少的利润。尽管有许多地方热心人士的努力,南方的工业化水平依然低,工资低、技能要求低,且主要以资源开采为主。南方工人的收入显著低于全国同行:南方纺织工人的收入仅为非南方纺织工人的75%,南方钢铁工人的收入为非南方工人的60%,而木材工人的收入仅为非南方工人的45%。在股市崩盘时,南方人已经是薪水低、食物短缺、教育匮乏的群体。

Major New Deal programs were designed with the South in mind. FDR hoped that by drastically decreasing the amount of land devoted to cotton, the AAA would arrest its long-plummeting price decline. Farmers plowed up existing crops and left fields fallow, and the market price did rise. But in an agricultural world of landowners and landless farmworkers (such as tenants and sharecroppers), the benefits of the AAA bypassed the southerners who needed them most. The government relied on landowners and local organizations to distribute money fairly to those most affected by production limits, but many owners simply kicked tenants and croppers off their land, kept the subsidy checks for keeping those acres fallow, and reinvested the profits in mechanical farming equipment that further suppressed the demand for labor. Instead of making farming profitable again, the AAA pushed landless southern farmworkers off the land.

新政的主要项目是专门为南方设计的。罗斯福希望通过大幅减少用于种植棉花的土地,农业调整局(AAA)能够遏制棉花价格的长期下跌。农民们耕种了现有作物,休耕了部分土地,市场价格确实有所回升。但在一个由地主和无地农民(如佃农和租种者)构成的农业世界中,AAA的好处并未惠及最需要帮助的南方人。政府依赖地主和地方组织公平分配限产补贴,但许多地主干脆将佃农和租种者赶出土地,将补贴支票拿到手,并将资金重新投资到机械化农具上,进一步压低了对劳动的需求。AAA没有使农业再次变得有利可图,反而将无地的南方农民赶出了土地。

But Roosevelt’s assault on southern poverty took many forms. Southern industrial practices attracted much attention. The NRA encouraged higher wages and better conditions. It began to suppress the rampant use of child labor in southern mills and, for the first time, provided federal protection for unionized workers all across the country. Those gains were eventually solidified in the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which set a national minimum wage of $0.25/hour (eventually rising to $0.40/hour). The minimum wage disproportionately affected low-paid southern workers and brought southern wages within the reach of northern wages.

然而,罗斯福对南方贫困的攻击采取了多种形式。南方的工业化做法引起了广泛关注。国家复兴局(NRA)鼓励提高工资和改善工作条件。它开始抑制南方工厂中猖獗的童工使用,并首次为全美工会工人提供了联邦保护。这些成果最终在1938年《公平劳动标准法》中得到巩固,该法规定了全国最低工资标准为每小时0.25美元(最终上升到0.40美元)。最低工资对南方低薪工人影响尤为显著,并将南方的工资水平推高到了接近北方的水平。

The president’s support for unionization further impacted the South. Southern industrialists had proven themselves ardent foes of unionization, particularly in the infamous southern textile mills. In 1934, when workers at textile mills across the southern Piedmont struck over low wages and long hours, owners turned to local and state authorities to quash workers’ groups, even as they recruited thousands of strikebreakers from the many displaced farmers swelling industrial centers looking for work. But in 1935 the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, guaranteed the rights of most workers to unionize and bargain collectively. And so unionized workers, backed by the support of the federal government and determined to enforce the reforms of the New Deal, pushed for higher wages, shorter hours, and better conditions. With growing success, union members came to see Roosevelt as a protector of workers’ rights. Or, as one union leader put it, an “agent of God.”

总统对工会化的支持进一步影响了南方。南方的工业家一向是工会化的坚决反对者,尤其是在臭名昭著的南方纺织厂。1934年,当南方皮埃蒙特地区的纺织厂工人因低工资和长工时而罢工时,厂主转而寻求地方和州政府的支持,以镇压工人组织,尽管他们从大量失业农民中招募了成千上万的打工者,这些农民涌向工业中心寻找工作。然而,1935年,《国家劳动关系法案》即“瓦格纳法案”通过,保障了大多数工人组织工会并集体谈判的权利。因此,工会工人得到了联邦政府的支持,并决心执行新政的改革,争取更高的工资、更短的工作时间和更好的工作条件。随着成功的增多,工会成员开始将罗斯福视为工人权利的保护者。正如一位工会领袖所说,他是“上帝的代言人”。

Perhaps the most successful New Deal program in the South was the TVA, an ambitious program to use hydroelectric power, agricultural and industrial reform, flood control, economic development, education, and healthcare to radically remake the impoverished watershed region of the Tennessee River. Though the area of focus was limited, Roosevelt’s TVA sought to “make a different type of citizen” out of the area’s penniless residents. The TVA built a series of hydroelectric dams to control flooding and distribute electricity to the otherwise nonelectrified areas at government-subsidized rates. Agents of the TVA met with residents and offered training and general education classes to improve agricultural practices and exploit new job opportunities. The TVA encapsulates Roosevelt’s vision for uplifting the South and integrating it into the larger national economy.

或许在南方最成功的新政项目是田纳西河流域管理局(TVA),这是一个雄心勃勃的计划,旨在利用水力发电、农业和工业改革、洪水控制、经济发展、教育和医疗等手段,彻底改造贫困的田纳西河流域地区。尽管关注的范围有限,罗斯福的TVA旨在“造就一种不同类型的公民”,把贫困地区的居民转变为更具生产力的公民。TVA建造了一系列水电大坝,以控制洪水并将电力分配到政府补贴的未通电地区。TVA的工作人员与居民会面,提供培训和普通教育课程,以改善农业实践并开发新的就业机会。TVA概括了罗斯福提升南方、将其融入更广泛国家经济的愿景。

Roosevelt initially courted conservative southern Democrats to ensure the legislative success of the New Deal, all but guaranteeing that the racial and economic inequalities of the region remained intact, but by the end of his second term, he had won the support of enough non-southern voters that he felt confident confronting some of the region’s most glaring inequalities. Nowhere was this more apparent than in his endorsement of a report, formulated by a group of progressive southern New Dealers, titled “A Report on Economic Conditions in the South.” The pamphlet denounced the hardships wrought by the southern economy—in his introductory letter to the report, Roosevelt called the region “the Nation’s No. 1 economic problem”—and blasted reactionary southern anti–New Dealers. He suggested that the New Deal could save the South and thereby spur a nationwide recovery. The report was among the first broadsides in Roosevelt’s coming reelection campaign that addressed the inequalities that continued to mark southern and national life.

罗斯福最初争取保守的南方民主党人的支持,以确保新政立法的成功,这几乎确保了该地区的种族和经济不平等仍然保持不变。但到他第二任期结束时,他已经赢得了足够多的非南方选民的支持,认为自己有能力挑战一些南方最为显著的不平等现象。没有比他对由一群进步派南方新政人士制定的报告《南方经济状况报告》的支持更明显的了。这份小册子抨击了南方经济带来的困难——在给报告的前言中,罗斯福称南方为“国家头号经济问题”——并猛烈攻击了反对新政的南方反对者。他指出,新政可以拯救南方,并进而推动全国的复苏。该报告成为罗斯福即将展开的连任竞选中的第一次攻势,着重讨论了南方和全国生活中依然存在的不平等现象。

IX. Voices of Protest

九、抗议之声

Despite the unprecedented actions taken in his first year in office, Roosevelt’s initial relief programs could often be quite conservative. He had usually been careful to work within the bounds of presidential authority and congressional cooperation. And, unlike Europe, where several nations had turned toward state-run economies, and even fascism and socialism, Roosevelt’s New Deal demonstrated a clear reluctance to radically tinker with the nation’s foundational economic and social structures. Many high-profile critics attacked Roosevelt for not going far enough, and, beginning in 1934, Roosevelt and his advisors were forced to respond.

尽管罗斯福在上任的第一年采取了前所未有的行动,但他最初的救济计划往往相当保守。他通常小心翼翼地在总统权力和国会合作的界限内运作。与欧洲不同,欧洲一些国家转向了由国家主导的经济体制,甚至是法西斯主义和社会主义,而罗斯福的新政则表明他明显不愿意彻底动摇国家的基本经济和社会结构。许多高调的批评者批评罗斯福没有走得更远,从1934年起,罗斯福和他的顾问们不得不做出回应。

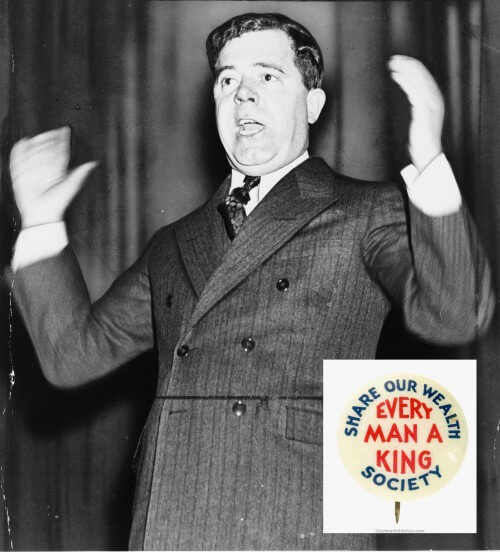

Senator Huey Long, a flamboyant Democrat from Louisiana, was perhaps the most important “voice of protest.” Long’s populist rhetoric appealed to those who saw deeply rooted but easily addressed injustice in the nation’s economic system. Long proposed a Share Our Wealth program in which the federal government would confiscate the assets of the extremely wealthy and redistribute them to the less well-off through guaranteed minimum incomes. “How many men ever went to a barbecue and would let one man take off the table what’s intended for nine-tenths of the people to eat?” he asked. Over twenty-seven thousand Share the Wealth clubs sprang up across the nation as Long traveled the country explaining his program to crowds of impoverished and unemployed Americans. Long envisioned the movement as a stepping-stone to the presidency, but his crusade ended in late 1935 when he was assassinated on the floor of the Louisiana state capitol. Even in death, however, Long convinced Roosevelt to more stridently attack the Depression and American inequality.

路易斯安那州的民主党参议员休伊·朗(Huey Long)或许是最重要的“抗议之声”。朗的民粹主义言辞吸引了那些看到了国家经济制度中深深根植、但却可以轻松解决的不公正现象的人们。朗提出了一项“共享财富”计划,联邦政府将没收极其富有者的资产,并通过保障最低收入将其重新分配给较不富裕的人群。“有多少人在参加烧烤时,会允许一个人把本该是九分之一人份的食物拿走?”他问道。在朗的倡导下,全国各地出现了超过27,000个“共享财富”俱乐部,朗则在全国各地旅行,向贫困和失业的美国人群体解释他的计划。朗将这一运动视为通向总统职位的垫脚石,但在1935年底,他在路易斯安那州议会大楼被暗杀,运动宣告结束。然而,即便在死亡后,朗依然促使罗斯福更加坚定地攻击大萧条和美国的社会不平等。

But Huey Long was not alone in his critique of Roosevelt. Francis Townsend, a former doctor and public health official from California, promoted a plan for old-age pensions which, he argued, would provide economic security for the elderly (who disproportionately suffered poverty) and encourage recovery by allowing older workers to retire from the workforce. Reverend Charles Coughlin, meanwhile, a priest and radio personality from the suburbs of Detroit, Michigan, gained a following by making vitriolic, anti-Semitic attacks on Roosevelt for cooperating with banks and financiers and proposing a new system of “social justice” through a more state-driven economy instead. Like Long, both Townsend and Coughlin built substantial public followings.

但休伊·朗并不是唯一对罗斯福提出批评的人。来自加利福尼亚的前医生和公共卫生官员弗朗西斯·汤森(Francis Townsend)提出了一项老年养老金计划,他认为该计划能为老年人(这一群体遭遇贫困的比例较高)提供经济保障,并通过允许老年工人从劳动力市场上退休来促进经济复苏。与此同时,来自底特律郊区的神父兼广播名人查尔斯·考赫林(Charles Coughlin)通过对罗斯福与银行家和金融家的合作进行猛烈的反犹太主义攻击,赢得了许多追随者,并提出通过一个更加国家主导的经济体制来实现“社会正义”的新体系。像朗一样,汤森和考赫林也吸引了大量的公众支持。

If many Americans urged Roosevelt to go further in addressing the economic crisis, the president faced even greater opposition from conservative politicians and business leaders. By late 1934, complaints increased from business-friendly Republicans about Roosevelt’s willingness to regulate industry and use federal spending for public works and employment programs. In the South, Democrats who had originally supported the president grew more hostile toward programs that challenged the region’s political, economic, and social status quo. Yet the greatest opposition came from the Supreme Court, filled with conservative appointments made during the long years of Republican presidents.

如果许多美国人呼吁罗斯福在应对经济危机方面采取更进一步的行动,那么总统则面临来自保守派政治家和商界领袖的更大反对。到1934年底,支持商业的共和党人对罗斯福愿意监管工业,并通过联邦支出进行公共工程和就业项目表示越来越多的抱怨。在南方,最初支持罗斯福的民主党人对挑战该地区政治、经济和社会现状的项目越来越持敌对态度。然而,最大的反对来自最高法院,这个法院由长期共和党总统任命的保守派法官组成。

By early 1935 the Court was reviewing programs of the New Deal. On May 27, a day Roosevelt’s supporters called Black Monday, the justices struck down one of the president’s signature reforms: in a case revolving around poultry processing, the Court unanimously declared the NRA unconstitutional. In early 1936, the AAA fell.

到了1935年初,最高法院开始审查新政的项目。1935年5月27日,罗斯福的支持者称这一天为“黑色星期一”,最高法院裁定总统的一项标志性改革——关于家禽加工的案件,法院一致宣判国家复兴局(NRA)违宪。1936年初,农业调整局(AAA)也相继被推翻。

X. The “Second” New Deal (1935-1936)

十、第二次新政(1935-1936)

The New Deal enjoyed broad popularity. Democrats gained seats in the 1934 midterm elections, securing massive majorities in both the House and Senate. Bolstered by these gains, facing reelection in 1936, and confronting rising opposition from both the left and the right, Roosevelt rededicated himself to bold programs and more aggressive approaches, a set of legislation often termed the Second New Deal. It included a nearly five-billion dollar appropriation that in 1935 established the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a permanent version of the CWA, which would ultimately employ millions of Americans on public works projects. It would employ “the maximum number of persons in the shortest time possible,” Roosevelt said. Americans employed by the WPA paved more than half-a-million miles of roads, constructed thousands of bridges, built schools and post offices, and even painted murals and recorded oral histories. Not only did the program build much of America’s physical infrastructure, it came closer than any New Deal program to providing the federal jobs guarantee Roosevelt had promised in 1932.

新政广受欢迎。1934年中期选举中,民主党赢得了大量席位,在众议院和参议院中获得了压倒性多数。借助这些胜利,罗斯福在面临1936年连任选举以及来自左右两方不断增加的反对声音时,重新致力于更大胆的计划和更激进的措施,这些立法通常被称为第二次新政。第二次新政包括了近50亿美元的拨款,并在1935年成立了“公共工程进展管理局”(WPA),这是一个永久性的CWA版本,最终将雇佣数百万美国人从事公共工程项目。罗斯福表示:“它将以最短的时间雇佣最多数量的人。”WPA雇佣的美国人修建了超过50万英里的道路,建造了数千座桥梁,建设了学校和邮局,甚至创作壁画和录制口述历史。这个项目不仅建造了美国的大部分基础设施,而且比任何新政计划都更接近实现罗斯福在1932年承诺的联邦就业保障。

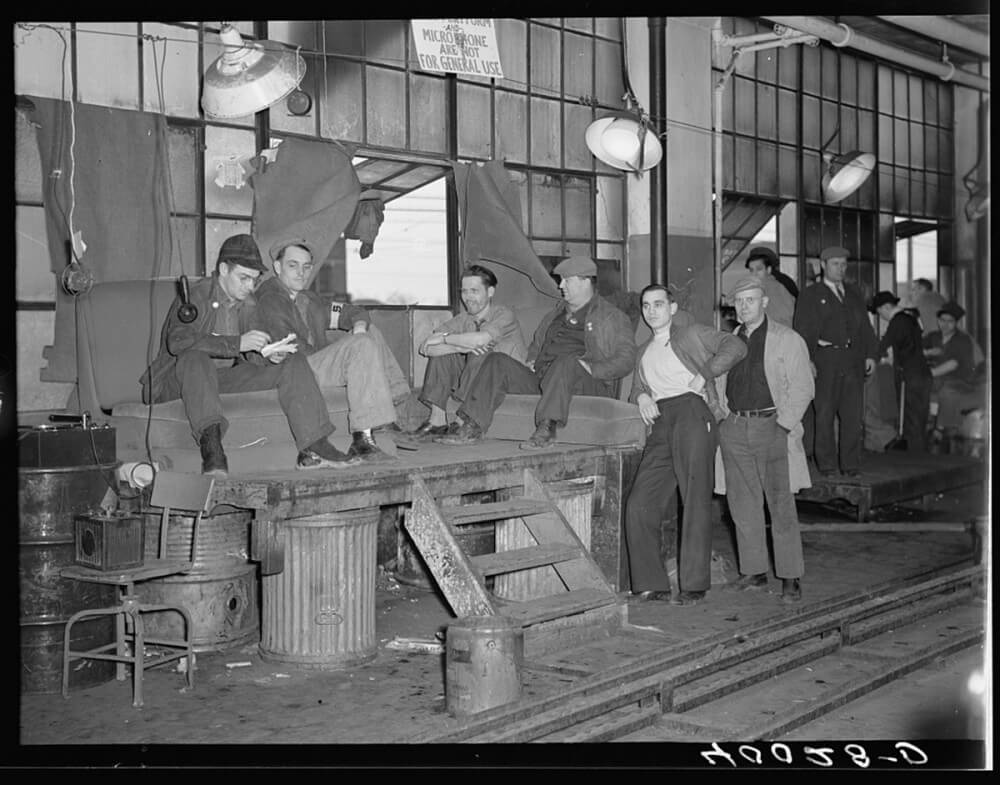

Also in 1935, hoping to reconstitute some of the protections afforded workers in the now-defunct NRA, Roosevelt worked with Congress to pass the National Labor Relations Act (known as the Wagner Act for its chief sponsor, New York senator Robert Wagner), offering federal legal protection, for the first time, for workers to organize unions. The labor protections extended by Roosevelt’s New Deal were revolutionary. In northern industrial cities, workers responded to worsening conditions by banding together and demanding support for workers’ rights. In 1935, the head of the United Mine Workers, John L. Lewis, took the lead in forming a new national workers’ organization, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), breaking with the more conservative, craft-oriented AFL. The CIO won a major victory in 1937 when affiliated members in the United Automobile Workers (UAW) struck for recognition and better pay and hours at a General Motors (GM) plant in Flint, Michigan. Launching a “sit-down” strike, the workers remained in the building until management agreed to negotiate. GM recognized the UAW and granted a pay increase. GM’s recognition gave the UAW new legitimacy and unionization spread rapidly across the auto industry. Across the country, unions and workers took advantage of the New Deal’s protections to organize and win major concessions from employers. Three years after the NLRA, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act, creating the modern minimum wage.

同样在1935年,罗斯福希望重建一些原由已经废除的NRA(国家复兴局)所提供的劳动者保护。他与国会合作,通过了《国家劳工关系法》(即“瓦格纳法案”,以其主要支持者、纽约州参议员罗伯特·瓦格纳的名字命名),首次为工人提供了联邦法律保护,允许他们组织工会。罗斯福新政所延伸的劳动保护具有革命性。在北方的工业城市,工人们对日益恶化的工作条件作出回应,联合起来,要求支持工人权益。1935年,联合矿工工会(UMW)主席约翰·L·刘易斯领导成立了一个新的全国性工人组织——“工业组织大会”(CIO),并与更加保守、以工艺为导向的美国劳联(AFL)决裂。1937年,CIO获得了一项重大胜利,当时隶属于联合汽车工人(UAW)的成员在密歇根州弗林特的通用汽车(GM)厂发起了罢工,要求厂方承认工会并改善工资和工时。工人们发起了“占座”罢工,坚守在厂区,直到管理层同意谈判。通用汽车公司最终承认了UAW并提高了工资。GM的承认赋予了UAW新的合法性,工会化迅速在汽车行业蔓延。在全国范围内,工会和工人利用新政的保护,组织起来,迫使雇主做出重大让步。三年后,国会通过了《公平劳动标准法》,设立了现代最低工资制度。

The Second New Deal also oversaw the restoration of a highly progressive federal income tax, mandated new reporting requirements for publicly traded companies, refinanced long-term home mortgages for struggling homeowners, and attempted rural reconstruction projects to bring farm incomes in line with urban ones. Perhaps the signature piece of Roosevelt’s Second New Deal, however, was the Social Security Act. It provided for old-age pensions, unemployment insurance, and economic aid, based on means, to assist both the elderly and dependent children. The president was careful to mitigate some of the criticism from what was, at the time, in the American context, a revolutionary concept. He specifically insisted that social security be financed from payroll, not the federal government; “No dole,” Roosevelt said repeatedly, “mustn’t have a dole.” He thereby helped separate social security from the stigma of being an undeserved “welfare” entitlement. While such a strategy saved the program from suspicions, social security became the centerpiece of the modern American social welfare state. It was the culmination of a long progressive push for government-sponsored social welfare, an answer to the calls of Roosevelt’s opponents on the Left for reform, a response to the intractable poverty among America’s neediest groups, and a recognition that the government would now assume some responsibility for the economic well-being of its citizens. Nevertheless, the act excluded large swaths of the American population. Its pension program excluded domestic workers and farm workers, for instance, a policy that disproportionately affected African Americans. Roosevelt recognized that social security’s programs would need expansion and improvement. “This law,” he said, “represents a cornerstone in a structure which is being built but is by no means complete.”

第二次新政还监督了高度进步的联邦所得税恢复,要求公开上市公司进行新的报告义务,为困难的房主重新融资长期抵押贷款,并尝试开展农村重建项目,以使农民收入与城市收入接轨。然而,罗斯福第二次新政的标志性内容是《社会保障法》。该法提供了老年养老金、失业保险和基于收入的经济援助,以帮助老年人和依赖子女。总统特别小心地缓解了当时在美国背景下,这一具有革命性的概念所带来的批评。他特别坚持,社会保障应当通过工资单进行资助,而非由联邦政府出资;“没有救济金,”罗斯福一再强调,“不能有救济金。”通过这种方式,他帮助将社会保障从“福利”特权的污名中分离开来。虽然这种策略使该计划避免了怀疑,但社会保障法成为了现代美国社会福利国家的核心。它是长期以来进步主义推动政府资助的社会福利的顶点,是对罗斯福左翼反对者改革呼声的回应,也是对美国最贫困群体的顽固贫困的回应,标志着政府将承担起公民经济福祉的一部分责任。然而,该法案排除了美国人口中的大量群体。例如,其养老金计划排除了家庭工人和农场工人,这一政策对非裔美国人造成了不成比例的影响。罗斯福认识到社会保障计划需要扩展和改善。他说:“这项法律代表了正在建设的结构中的一个基石,但它远未完成。”

XI. Equal Rights and the New Deal

十一、平等权利与新政

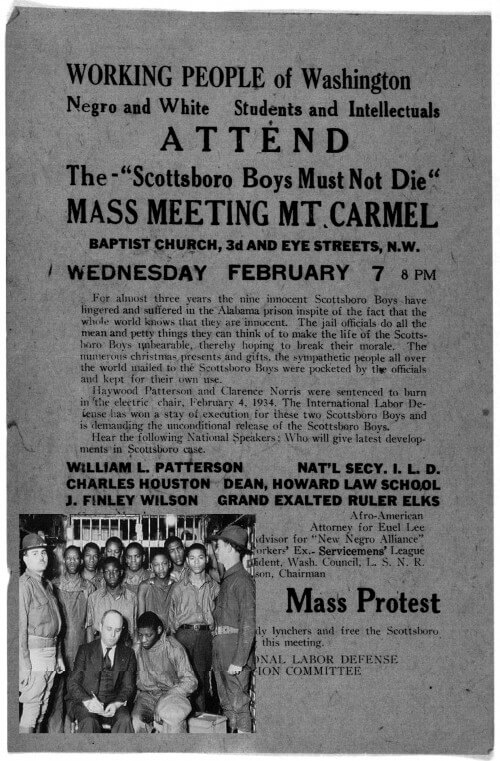

Black Americans faced discrimination everywhere but suffered especially severe legal inequality in the Jim Crow South. In 1931, for instance, a group of nine young men riding the rails between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee, were pulled from the train near Scottsboro, Alabama, and charged with assaulting two white women. Despite clear evidence that the assault had not occurred, and despite one of the women later recanting, the young men endured a series of sham trials in which all but one were sentenced to death. Only the communist-oriented International Labor Defense (ILD) came to the aid of the “Scottsboro Boys,” who soon became a national symbol of continuing racial prejudice in America and a rallying point for civil rights–minded Americans. In appeals, the ILD successfully challenged the boys’ sentencing, and the death sentences were either commuted or reversed, although the last of the accused did not receive parole until 1946.

黑人美国人在各地面临歧视,尤其在吉姆·克劳法治下的南方,法律上受到的压迫更为严重。例如,1931年,一群九名年轻男子在田纳西州的查塔努加与孟菲斯之间乘火车时,在阿拉巴马州的斯科茨伯勒被从火车上拉下,指控袭击两名白人女性。尽管有明确证据表明袭击没有发生,而且其中一位女性后来撤回了指控,这些年轻人仍然经历了一系列虚假的审判,除了其中一人外,其他人都被判死刑。唯一一个在共产党支持的国际劳动辩护(ILD)组织的帮助下被救助的“斯科茨伯勒男孩”成为了美国种族偏见继续存在的国家象征,也成为了民权活动人士的集结点。通过上诉,ILD成功地挑战了这些男孩的判决,死刑判决要么被减轻,要么被撤销,尽管最后一位被告直到1946年才获得假释。

Despite a concerted effort to appoint Black advisors to some New Deal programs, Franklin Roosevelt did little to specifically address the particular difficulties Black communities faced. To do so openly would provoke southern Democrats and put his New Deal coalition—–the uneasy alliance of national liberals, urban laborers, farm workers, and southern whites—at risk. Roosevelt not only rejected such proposals as abolishing the poll tax and declaring lynching a federal crime, he refused to specifically target African American needs in any of his larger relief and reform packages. As he explained to the national secretary of the NAACP, “I just can’t take that risk.”

尽管罗斯福政府在一些新政计划中确实努力任命黑人顾问,但他对黑人社区面临的特殊困境几乎没有作出直接回应。公开提出这些问题会激怒南方的民主党人,并使他的新政联盟——这一由全国性自由派、城市工人、农场工人和南方白人组成的松散联盟——面临风险。罗斯福不仅拒绝废除投票税和将私刑定为联邦犯罪的提议,还拒绝在他的更大范围的救济与改革计划中明确关注非裔美国人的需求。正如他对全国有色人种协进会(NAACP)秘书长所解释的那样:“我无法冒这个险。”

In fact, many of the programs of the New Deal had made hard times more difficult. When the codes of the NRA set new pay scales, they usually took into account regional differentiation and historical data. In the South, where African Americans had long suffered unequal pay, the new codes simply perpetuated that inequality. The codes also exempted those involved in farm work and domestic labor, the occupations of a majority of southern Black men and women. The AAA was equally problematic as owners displaced Black tenants and sharecroppers, many of whom were forced to return to their farms as low-paid day labor or to migrate to cities looking for wage work.

事实上,许多新政计划反而让黑人美国人面临更大的困境。当NRA(国家复兴局)的规定设定新的薪酬标准时,它通常考虑到地区差异和历史数据。而在南方,黑人长期以来在工资上受到不平等待遇,这些新规仅仅是延续了这种不平等。这些规定还排除了从事农业劳动和家庭劳动的人员,这些正是大多数南方黑人男女的职业。AAA(农业调整法案)也同样存在问题,因为土地所有者将黑人租户和佃农驱逐,而许多人被迫回到农田做低薪日工,或者迁移到城市寻找薪资工作。

Perhaps the most notorious failure of the New Deal to aid African Americans came with the passage of the Social Security Act. Southern politicians chafed at the prospect of African Americans benefiting from federally sponsored social welfare, afraid that economic security would allow Black southerners to escape the cycle of poverty that kept them tied to the land as cheap, exploitable farm laborers. The Jackson (Mississippi) Daily News callously warned that “The average Mississippian can’t imagine himself chipping in to pay pensions for able-bodied Negroes to sit around in idleness . . . while cotton and corn crops are crying for workers.” Roosevelt agreed to remove domestic workers and farm laborers from the provisions of the bill, excluding many African Americans, already laboring under the strictures of legal racial discrimination, from the benefits of an expanding economic safety net.

或许新政在援助黑人方面最著名的失败体现在《社会保障法》的通过上。南方的政治家们对黑人能够受益于联邦资助的社会福利感到不满,担心经济保障会让黑人南方人摆脱贫困的恶性循环,这一循环使他们长期被束缚在土地上,成为廉价、可剥削的农场劳工。《杰克逊日报》冷酷地警告说:“普通的密西西比人无法想象自己要为体壮的黑人支付养老金,让他们坐在那儿无所事事……而棉花和玉米的收成则急需劳动力。”罗斯福同意从法案中剔除家庭工人和农场劳工,这样就将许多已经在法律种族歧视下辛苦劳作的黑人排除在扩大的经济安全网之外。

Women, too, failed to receive the full benefits of New Deal programs. On one hand, Roosevelt included women in key positions within his administration, including the first female cabinet secretary, Frances Perkins, and a prominently placed African American advisor in the National Youth Administration, Mary McLeod Bethune. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was a key advisor to the president and became a major voice for economic and racial justice. But many New Deal programs were built on the assumption that men would serve as breadwinners and women as mothers, homemakers, and consumers. New Deal programs aimed to help both but usually by forcing such gendered assumptions, making it difficult for women to attain economic autonomy. New Deal social welfare programs tended to funnel women into means-tested, state-administered relief programs while reserving entitlement benefits for male workers, creating a kind of two-tiered social welfare state. And so, despite great advances, the New Deal failed to challenge core inequalities that continued to mark life in the United States.

女性同样未能完全享受到新政计划的福利。一方面,罗斯福在政府内提拔了许多女性担任重要职位,包括第一位女性内阁部长弗朗西斯·珀金斯,以及在国家青年管理局担任显赫职务的非裔美国人顾问玛丽·麦克劳德·贝瑟恩。第一夫人埃莉诺·罗斯福是总统的主要顾问,并成为经济和种族正义的重要声音。然而,许多新政计划建立在男性担任养家糊口者,女性担任母亲、家庭主妇和消费者的假设基础上。新政计划旨在帮助两者,但通常是通过强化这种性别角色假设,使女性难以获得经济独立。新政的社会福利项目通常将女性引导到基于经济条件的、由国家管理的救济计划中,而将男性工人纳入有权利获得的福利中,形成了两层的社会福利体系。因此,尽管取得了巨大进展,但新政未能挑战继续影响美国生活的核心不平等现象。

XII. The End of the New Deal (1937-1939)

十二、新政的终结(1937-1939)

By 1936, Roosevelt and his New Deal won record popularity. In November, Roosevelt annihilated his Republican challenger, Governor Alf Landon of Kansas, who lost in every state save Maine and Vermont. The Great Depression had certainly not ended, but it appeared to be retreating, and Roosevelt, now safely reelected, appeared ready to take advantage of both his popularity and the improving economic climate to press for even more dramatic changes. But conservative barriers continued to limit the power of his popular support. The Supreme Court, for instance, continued to gut many of his programs.

到了1936年,罗斯福和他的新政获得了创纪录的支持率。在11月的选举中,罗斯福将他的共和党对手——堪萨斯州州长阿尔夫·兰登击败,除了缅因州和佛蒙特州,其他所有州都输给了他。大萧条虽然没有完全结束,但似乎正在逐渐退去,罗斯福在成功连任后,准备借助自己的人气和经济形势的改善,推动更为剧烈的改革。然而,保守派的障碍仍然限制着他广泛支持的力量。最高法院继续削弱许多新政计划。

In 1937, concerned that the Court might overthrow social security in an upcoming case, Roosevelt called for legislation allowing him to expand the Court by appointing a new, younger justice for every sitting member over age seventy. Roosevelt argued that the measure would speed up the Court’s ability to handle a growing backlog of cases; however, his “court-packing scheme,” as opponents termed it, was clearly designed to allow the president to appoint up to six friendly, pro–New Deal justices to drown the influence of old-time conservatives on the Court. Roosevelt’s “scheme” riled opposition and did not become law, but the chastened Court thereafter upheld social security and other pieces of New Deal legislation. Moreover, Roosevelt was slowly able to appoint more amenable justices as conservatives died or retired. Still, the court-packing scheme damaged the Roosevelt administration emboldened New Deal opponents.

1937年,罗斯福担心法院可能会推翻社会保障法案,于是提议立法,允许他为每位年满七十岁的现任法官任命一名年轻的法官。罗斯福辩称,这项措施将加速法院处理积压案件的能力;然而,反对者称之为“法院填充计划”,明显目的是让总统任命最多六位支持新政的法官,从而削弱保守派法官在法院中的影响力。罗斯福的“计划”引发了激烈反对,并未成为法律,但法院在此后的判决中支持了社会保障法案及其他新政立法。此外,随着保守派法官的去世或退休,罗斯福逐渐能够任命更多支持改革的法官。然而,这一法院填充计划损害了罗斯福政府的形象,并使新政的反对者更加自信。

Compounding his problems, Roosevelt and his advisors made a costly economic misstep. Believing the United States had turned a corner, Roosevelt cut spending in 1937. The American economy plunged nearly to the depths of 1932–1933. Roosevelt reversed course and, adopting the approach popularized by the English economist John Maynard Keynes, hoped that countercyclical, compensatory spending would pull the country out of the recession, even at the expense of a growing budget deficit. It was perhaps too late. The Roosevelt Recession of 1937 became fodder for critics. Combined with the court-packing scheme, the recession allowed for significant gains by a conservative coalition of southern Democrats and Midwestern Republicans in the 1938 midterm elections. By 1939, Roosevelt struggled to build congressional support for new reforms, let alone maintain existing agencies. Moreover, the growing threat of war in Europe stole the public’s attention and increasingly dominated Roosevelt’s interests. The New Deal slowly receded into the background, outshined by war.

与此同时,罗斯福和他的顾问犯了一个代价惨重的经济错误。罗斯福相信美国已经度过了最困难的时期,因此在1937年削减了政府开支。这导致美国经济几乎跌入1932-1933年危机的深渊。罗斯福随即改变了政策,采纳了英国经济学家约翰·梅纳德·凯恩斯提出的对策,主张通过反周期的补偿性支出拉动经济,即便这意味着增加预算赤字。或许为时已晚。1937年的“罗斯福衰退”成为了批评者的攻击材料。加上法院填充计划的失败,1938年中期选举中,南方民主党人和中西部共和党人的保守派联盟获得了显著的胜利。到了1939年,罗斯福在争取国会支持新一轮改革方面陷入困境,甚至难以维持现有的各个政府机构。此外,欧洲战争的威胁逐渐加剧,分散了公众的注意力,战争开始成为罗斯福政府的主攻方向。新政逐渐退居幕后,战争的阴影逐渐笼罩了所有政治议题。

XIII. The Legacy of the New Deal

十三、新政的遗产

By the end of the 1930s, Roosevelt and his Democratic Congresses had presided over a transformation of the American government and a realignment in American party politics. Before World War I, the American national state, though powerful, had been a “government out of sight.” After the New Deal, Americans came to see the federal government as a potential ally in their daily struggles, whether finding work, securing a decent wage, getting a fair price for agricultural products, or organizing a union. Voter turnout in presidential elections jumped in 1932 and again in 1936, with most of these newly mobilized voters forming a durable piece of the Democratic Party that would remain loyal well into the 1960s. Even as affluence returned with the American intervention in World War II, memories of the Depression continued to shape the outlook of two generations of Americans. Survivors of the Great Depression, one man would recall in the late 1960s, “are still riding with the ghost—the ghost of those days when things came hard.”

到了1930年代末,罗斯福和他的民主党国会领导下,美国政府经历了转型,政党政治也发生了重新排列。在第一次世界大战之前,尽管美国国家机器强大,但它是一个“看不见的政府”。新政实施后,美国人开始把联邦政府视为他们日常生活中的潜在盟友,不论是寻找工作、确保体面的工资、为农产品争取公平价格,还是组织工会。1932年和1936年,选民的投票率大幅上升,许多新加入的选民成为了民主党的一支持久力量,这一群体在1960年代依然忠诚于该党。即便随着美国介入第二次世界大战,富裕回归,但大萧条的记忆仍然影响着两代美国人的世界观。大萧条的幸存者们,正如一位回忆录作者在1960年代末所说,“依旧和幽灵同行——那些日子的幽灵,那些日子里万事艰难。”

Historians debate when the New Deal ended. Some identify the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 as the last major New Deal measure. Others see wartime measures such as price and rent control and the G.I. Bill (which afforded New Deal–style social benefits to veterans) as species of New Deal legislation. Still others conceive of a “New Deal order,” a constellation of “ideas, public policies, and political alliances,” which, though changing, guided American politics from Roosevelt’s Hundred Days forward to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society—and perhaps even beyond. Indeed, the New Deal’s legacy still remains, and its battle lines still shape American politics.

历史学家们对于新政何时结束有不同的看法。一些学者认为1938年的《公平劳动标准法》是新政的最后一项重大立法。另一些学者认为二战期间的措施,如价格和租金管制以及《退伍军人法案》(该法案为退伍军人提供了类似新政的社会福利)也是新政式立法的一部分。还有一些学者认为,新政是一种“新政秩序”,它是一系列“理念、公共政策和政治联盟”的集合,尽管这些政策不断变化,但从罗斯福的百日新政到林登·约翰逊的“大社会”,甚至更远,始终指引着美国的政治走向。事实上,新政的遗产依然存在,其影响依旧塑造着美国政治的战线。